![]()

Una cabeza olmeca en Buenos Aires:

opciones del patrimonio

JOSÉ ANTONIO PÉREZ GOLLÁN, DIRECTOR DEL MUSEO ETNOGRÁFICO (FFYL-UBA)

“Lo que llamamos “obra de arte” –designación equívoca, sobre todo aplicada a las obras de las civilizaciones antiguas– no es tal vez sino una configuración de signos. Cada espectador combina esos signos de una manera distinta y cada combinación emite un significado diferente”.

Octavio Paz

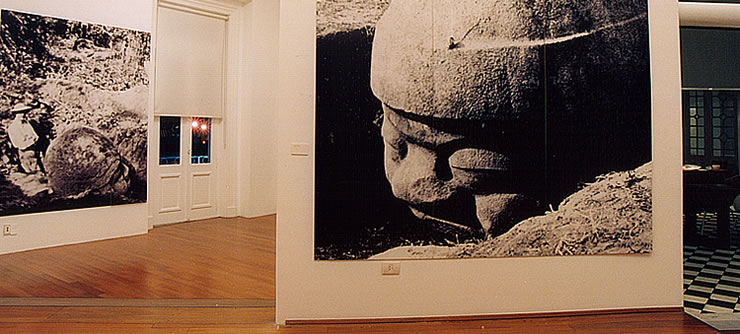

Las cabezas colosales olmecas talladas en piedra son quizá, junto con la pintura de Frida Kahlo y los murales de Diego Rivera, uno de los íconos más populares del arte mexicano. La exposición La magia de la risa y el juego en la sede de la Fundación Proa exhibe, por primera vez en la Argentina, una cabeza de piedra olmeca junto a un grupo de cerámicas modeladas: las denominadas caras sonrientes y algunos juguetes. Toda la muestra procede del actual estado de Veracruz en México y, además, reconoce una cierta continuidad en términos del desarrollo cronológico.

Son varios los motivos que me llevan a centrar la atención en la cabeza colosal olmeca: uno, y tal vez no el más importante, por mi formación de arqueólogo; otro, por la profunda curiosidad que me despierta el arte y su relación con los procesos sociales; por último, por mi condición de director de un museo universitario de antropología.

En esta exposición, la cultura olmeca está representada por una cabeza colosal que lleva el número 9 y fue hallada en 1982 de manera casual por un campesino, cerca de San Lorenzo (Veracruz). Hasta la fecha, son 17 las cabezas conocidas: diez proceden de San Lorenzo, cuatro de La Venta, dos de Tres Zapotes y una de Cobata; los ejemplares de cada una de estas localidades tienen su estilo propio y particular. Casi todas las cabezas han sido mutiladas en tiempos remotos, posiblemente con fines políticos.

El primer hallazgo de una cabeza colosal fue el que hizo José Melgar en 1862 y cuya noticia publicó en el Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística (1896). Pero fue Mathew Stirling quien en 1936 inició las investigaciones arqueológicas sistemáticas y modernas en la región olmeca; sus trabajos se prolongaron por varias décadas y tuvieron una notable influencia en la arqueología americana. Por su parte, el pintor, dibujante e ilustrador mexicano Miguel Covarrubias cumplió en las décadas de 1940 y 1950 un importante papel en la valorización de las sorprendentes y remotas manifestaciones olmecas desde la perspectiva artística.

En 1946 escribía en su libro El sur de México: “Según parece, una raza misteriosa de extraordinarios artistas vivió desde tiempos muy antiguos en el Istmo [deTehuantepec], sobre todo en los alrededores de Los Tuxtlas y la cuenca del río Coatzacoalcos. Por todas partes hay tesoros arqueológicos que yacen ocultos en las selvas y debajo de la rica tierra del sur de Veracruz: túmulos y pirámides funerarios; monumentos colosales de basalto tallados magistralmente; magníficas figurillas de precioso jade y otras de barro, modeladas con gran sensibilidad. Todos ellos de una gran calidad artística sin precedentes. La inasequible presencia de un pasado grandioso y remoto en lo que ahora es selva impenetrable y deshabitada, resulta un enigma aún más misterioso porque la mayoría de los antropólogos actuales coincide en afirmar que muchas de estas obras maestras artísticas datan de una época que retrocede hasta los comienzos de la era cristiana. Esta cultura, que aparece de pronto como surgida de la nada en un estado de completo desarrollo, parece haber sido la raíz, el origen de culturas posteriores y mejor conocidas: maya, totonaca, zapoteca, etc.”. Desde 1950 y en adelante, la aplicación del nuevo método del radiocarbono, al poder fechar los restos orgánicos, permitió establecer con aceptable precisión la antigüedad de los materiales arqueológicos, lo que confirmó que las tallas olmecas se remontaban al primer milenio AC.

El núcleo geográfico de la cultura olmeca corresponde a la parte sur del estado de Veracruz y la porción colindante de Tabasco. El paisaje se presenta allí como una planicie costera con lomadas bajas, que debido a su escasa altura sobre le nivel del mar se inunda con facilidad. El área está surcada por ríos de gran caudal, muchos de ellos navegables, y en cuyas desembocaduras se han formado amplios deltas: es el caso del río Coatzacoalcos, por ejemplo. La densa selva tropical que cubría la región, hoy casi ha desaparecido por las modernas prácticas agrícolas y ganaderas y, también, por la intensa explotación petrolera.

Todos los objetos líticos –máscaras, cabezas colosales, tronos, estelas, hachas, estatuillas, esculturas de bulto, etcétera– fueron tallados por los olmecas sólo con herramientas de piedra y madera, pues en Mesoamérica los metales eran desconocidos en esa época. La forma general de las piezas se lograba con instrumentos de piedra, se perforaban con el taladro de arco y para el desgaste y pulido se recurría a arenas o cenizas volcánicas. Lo que debe considerarse es el gran aporte de mano de obra que requería una técnica que podríamos calificar de neolítica, lo cual era coherente con los modos de organización de la fuerza de trabajo en las sociedades preindustriales.

Las materias primas procedían de regiones distantes; la piedra verde (jade, jadeíta, serpentina y otras) para los bienes de lujo se traía probablemente desde el actual estado de Guerrero (México) o del valle del río Motagua (Guatemala). Las cabezas colosales, por su parte, se tallaron en roca volcánica; las de la Venta, Tres Zapotes y Cobata en basalto, mientras que las de San Lorenzo en andesita. Los enormes bloques de roca proceden de canteras que quedan a 100 y 150 Km de distancia y lo más probable es que debieron transportarse en balsas a través de los ríos hasta sus emplazamientos definitivos.

En el área que los arqueólogos han definido como Mesoamérica y en una fecha tan temprana como el 2500 AC, se afianzó una nueva forma de organización social: se generalizó el sedentarismo agrícola, hubo un aumento de la población que se concentró en caseríos y aldeas. Los antiguos modos de vida de los cazadores recolectores fueron dejados atrás: en ese momento se multiplicaron las pequeñas comunidades igualitarias y autónomas asentadas junto a sus campos de cultivo que aprovecharon las lluvias estacionales, los suelos húmedos o los terrenos que inundan anualmente los ríos.

Hacia el 1200 AC, sobre la base de la anterior tradición, se incorporaron a la agricultura nuevas plantas y técnicas más complejas para controlar el agua a través del riego, se construyeron terrazas de cultivo para evitar la erosión y generar suelos artificiales, a la vez que se colonizaron espacios productivos: sin duda, aumentó el rendimiento de la tierra. Algunas comunidades iniciaron una incipiente especialización productiva y se organizó la circulación de materias primas, productos e ideas. Pero quizá lo más destacable es que por primera vez en la América indígena surgió la desigualdad social hereditaria. Los circuitos de intercambio se ampliaron hasta abarcar regiones remotas y se volvieron más complejos, a la vez que las emergentes elites locales pusieron en circulación bienes de lujo para acrecentar y afianzar su prestigio: vasos de cerámica policroma, espejos de hematita, polvo y colorantes, pieles, figurillas, piedras semipreciosas, plumas, caracoles y conchas. Existían en ese entonces linajes que por descender de un antepasado de prestigio mítico acumulaban poder –y lo transmitían por herencia a sus descendientes– como para asumir la representación de la comunidad y ser, sobre todo, los mediadores entre los hombres y las potencias sobrenaturales.

Muchas han sido y son las hipótesis para explicar el surgimiento de la desigualdad social hereditaria: el acceso diferencial a los recursos, el desarrollo tecnológico, la coordinación de las obras de irrigación, el control del intercambio y la redistribución de bienes de alto valor simbólico, el manejo de un marco ideológico complejo. En realidad, es mejor pensar en una conjunción de circunstancias, y no en un único factor como el detonante.

Alrededor del 1200 AC, San Lorenzo se constituyó en el asentamiento olmeca más importante y con mayor población: diez veces más grande que cualquiera de las aldeas de esa época. Por su ubicación en la cuenca media del Coatzacoalcos, controlaba los movimientos de bienes y personas a través de la red fluvial, a la vez que coordinaba la mano de obra y la producción especializada regional. También se modificó el terreno natural para dejar las marcas de un paisaje sagrado y monumental. Se construyeron largas y anchas terrazas que, al alterar la topografía, crearon nuevos espacios de habitación y producción para una población en aumento. A la vez, se diseñaron espacios ceremoniales mediante plataformas truncadas de tierra, bajas y escalonadas, muchas veces recubiertas con arena de color rojo. En este momento temprano de la arquitectura olmeca no hay evidencias de que se construyera según el modelo de plazas y pirámides característico de los centros ceremoniales mesoamericanos posteriores.

Podríamos preguntarnos, ¿qué es lo que cambió en San Lorenzo? El sistema socio-político es lo que se transformó: una línea de parentesco, un linaje, se impuso como grupo gobernante y desde entonces transmitió el poder como herencia a sus descendientes. De las anteriores comunidades igualitarias y autónomas, se pasó a una sociedad multicomunitaria aglutinada por el principio estructural del rango. En estas sociedades los linajes ocupaban distintas gradaciones (rangos) de prestigio en relación a un antepasado común (muchas veces mítico o sacralizado). Uno de estos linajes se reservaba el derecho hereditario al ejercicio del cargo político de jefe: un personaje de carácter sacrosanto, intermediario entre los hombres y los dioses en tanto supremo sacerdote, redistribuidor de los excedentes económicos que la comunidad aportaba –a modo de tributo– en productos o trabajo, coordinador de las obras comunitarias y, en algunos casos, propietario de las tierras. El jefe o señor poseía un séquito, su actividad estaba regida por un estricto protocolo y era la pieza principal de un complicado ritual público.

Las cabezas colosales fueron las representaciones de los jefes o señores con los atributos del poder; los antepasados transformados en piedra, que ofrecían testimonio de la legitimidad y sacralidad de los linajes gobernantes. En San Lorenzo estaban dispuestas, al parecer, según dos ejes que corren de norte a sur en la parte central del sitio. El tema dominante en la escultura monumental olmeca fue el de los hombres adultos del grupo gobernante que se representaron en las cabezas colosales, los personajes sentados y los tronos. El arte olmeca estuvo íntimamente ligado a la construcción del poder en el surgimiento de la desigualdad social hereditaria: en la cuenca del Coatzacoalcos se inició el camino de la América indígena hacia la civilización, el estado y la sociedad de clases. Con posterioridad al apogeo de San Lorenzo, el eje se desplazó primero hacia La Venta y más tarde a Tres Zapotes. Para el 300 AC el pueblo y el arte olmeca ya habían desaparecido.

La exhibición de la cabeza colosal olmeca de San Lorenzo (Veracruz) en la Fundación Proa, pone en juego otros conceptos que no son los de un arte arcaico cargado de los significados ideológicos que rodean al poder en los inicios de la sociedad urbana. Expuesta en la sala de un edificio construido a fines del siglo XIX que fue refaccionado para servir como centro de arte, la cabeza olmeca cobra sentido dentro de las categorías del arte moderno y aparece como antecedente de Botero o de las esculturas del argentino Claudio Barragán; así, en la Vuelta de Rocha, la cabeza 9 se convierte en nuestra contemporánea. Sin embargo, si se la exhibe en el contexto de la museografía nacionalista del siglo XX, anuncia –desde su monumentalidad precolombina– la emancipación del campesino y apuntala la identidad propuesta por el Estado nacional.

Todas son, al fin de cuenta, opciones del patrimonio: válidas en la medida en que cada contexto crea su observador y configura significados.

“What we call ‘a work of art’ –a wrong name mainly if referred to those works of ancient civilizations– isn’t but a configuration of signs. Spectators are able to combine those signs at will, and every combination will then result in a different meaning.”

Octavio Paz

Perhaps the colossal Olmeca heads carved in stone are, together with Frida Kahlo’s paintings and Diego Rivera’s mural paintings, one of the most popular icons in Mexican art. The exhibition La magia de la risa y el juego (The magic of laugh and game) in the halls of Fundacion Proa will show, for the first time ever in South America, an Olmeca stone head together with a series of hand made pottery items –the ones called caras sonrientes (smiling faces) as well as some toys. All the pieces in display come from what is now the State of Veracruz, in Mexico and show certain continuity in terms of their chronological development.

There are several reasons for me to concentrate on the colossal Olmeca head. One of them, though not the most important, is connected to the fact I’m an archaeologist. Another one is the curiosity I feel for art when this is related to social processes. One more reason, the last, is my position as head of a university museum of anthropology.

In this exhibition, the Olmeca culture is represented by a gigantic stone head (that identified under Number Nine) which was accidentally found by a peasant near San Lorenzo (Veracruz) in 1982. There are seventeen such heads known to this day –ten come from San Lorenzo, four from La Venta, two from Tres Zapotes and one from Cobata. The samples coming from each of these places have a style of their own. Almost all of them have been somehow mutilated in ancient times –maybe due to political purposes.

The first finding of a stone head ever was that made by José Melgar in 1862 and the news was published in the Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística (1896). But it was Mathew Stirling who in 1936 started a systematic contemporary archaeological investigation in the Olmeca region. His work took several decades and had a notable influence on the archaeology of the American continent. On the other hand, Miguel Covarrubias –a Mexican painter, drawer and illustrator– played, during the 1940s and 50s, a most important role in the valuation of the surprising and remote Olmeca artistic manifestations.

In 1946 he stated in his book El Sur de México: “It all seems to indicate that a mysterious race of extraordinary artists lived since remote times in the Tehuantepec isthmus, mainly in the environs of Los Tuxtlas and the basin of the Coatzacoalcos river. There are archaeological treasures still hidden in the jungle and the rich lands south of Veracruz: grave mounds and funeral pyramids, colossal monuments masterfully carved in basalt, wonderful figurines made of axestone and others delicately modeled in clay. They are all of an artistic quality that knows no parallel. The inaccessible presence of a magnificent remote past in what now is the impenetrable, uninhabited jungle is an enigma and this grows even bigger since most contemporary anthropologists agree as to the fact many of these works of art date back to the beginnings of the Christian era. This culture that, out of the blue, appears in a state of full development, seems to have been the root, the origin of succeeding and better known cultures known as Maya, Totonaca, Zapoteca, etc.” From 1950 onwards the application of the new method of radiocarbon made it possible to establish with acceptable accuracy the age of the archaeological materials and this proved the Olmeca sculptures dated back to the second millennium B.C.

The geographic nucleus of the Olmeca culture is to be found in the southern part of the State of Veracruz and the neighboring area of Tabasco. The landscape there is a coastal plain with hillocks that gets easily flooded. The area is crossed by plentiful rivers –most of them navigable– and their mouths have created large deltas. This is the case of River Coatzacoalcos, for instance. The thick tropical jungle that used to cover this region has now disappeared due to modern agriculture and cattle raising as well as by the intensity of the oil drilling activity.

All the lithic objects –masks, colossal heads, thrones, steles, axes, statuettes, sculptures, etc.– were made by the Olmeca people only with the use of stone and wooden tools since metals were unknown to the Mesoamericans of those times. The general shape of the art pieces was attained with the use of stone instruments. They were perforated using a bow drill; sand or volcanic ashes were used to produce polished surfaces. One must also bear in mind the great amount of hand labor such a technique we now call Neolithic really demanded. This corresponds with the modes of organization of the task force in pre-industrial societies.

The raw materials came from distant regions: the green stone (axestone, jade, serpentine and others) used for luxury goods was brought from what is now the State of Guerrero (Mexico) or from the valley of river Motagua (Guatemala). As regards the colossal heads, these were carved out of volcanic rock: cobalt was used for those of La Venta, Tres Zapotes y Cobata while andesita was used for the ones from San Lorenzo. The huge rock blocks came from quarries that were a hundred or a hundred and fifty kilometers far from any of the spots they were going to be finally placed and most probably they were carried there on rafts along the rivers.

In the area the archaeologists have defined as Mesoamerica and on a date as early back as 2500 B.C. a new type of social organization with sedentary people devoted to agriculture grew in number until it constituted hamlets and villages. The ancient ways of living on hunting and fruit gathering were abandoned. This moment meant a multiplication of the number of equalitarian, independent communities that grew round their cultivation fields, profiting from seasonal rains, fertile soils and those lands flooded by the rivers annually.

Around 1200 B.C. and on the traditional basis, agriculture was improved in terms of new plants, more elaborate watering control techniques, and the building of terraces to avoid erosion and create artificial soils as well as the settlement of new productive areas. All this augmented the yielding of those lands. Some communities started an incipient specialized production and the circulation of raw materials, products and ideas was organized. But what is most notable is the surge, for the first time in aboriginal America, of hereditary social inequity. The circuits of exchange grew until they reached far off regions and became more complex. At the same time, the local elites started to spread luxury goods to increase and consolidate their reputation: polychrome pottery vases, hematite mirrors, powders and dyeings, skins, figurines, semiprecious stones, feathers, shells and conches. Now some lineages had an ancestry of mythical prestige and they used it to make their power grow. This enabled them to assume the hereditary representation of a community and made them, in particular, the mediators between men and supernatural forces.

There were and there are several hypotheses to explain the appearance of hereditary social inequity. These consider the differential access to resources, technological development, the coordination of irrigation works, the control over the exchange and re-distribution of goods of a highly symbolic meaning, the management of a complex ideological frame. In fact, one should view this issue as a concurrence of circumstances rather than finding a single detonating cause.

Around 1200 B.C. San Lorenzo became the largest and the most important Olmeca settlement. The population was ten times larger than any of the villages of that time. Being in the middle basin of the Coatzacoalcos, this people were in control of the traffic of goods and people through the fluvial network, and they also coordinated hand labor and the specialized local production. The original terrain was modified to create a sacred, monumental landscape. Large, wide terraces were built and such topographic alteration meant new dwelling spaces as well as an increase in production to meet the demands of a growing population. On the other hand, ritual spaces were built –these were low, staired truncate earthen platforms, often coated with red tinted sand. During this early moment of the Olmeca architecture there is no evidence of any square or pyramid of the type that later on were to become typical of ceremonial Mesoamerican centers.

We could inquire what really changed in San Lorenzo. The answer is to be found in the socio-political system: it became a line of ancestors, a lineage, and this was imposed as the ruling group –one which transmitted power as inheritance to its descendants. The early equalitarian and autonomic communities were replaced by a multi-communal society bound together by the structural principle of rank. In these societies lineages had different gradations (ranks) of prestige in relation to a common ancestor (quite often mythic or sacralized). One of these lineages kept to itself the hereditary right to play the political role of a chieftain –a kind of sacred character, a high priest to mediate between men and the gods, one who re-distributed the economic surplus coming as a tribute from the work or production of the community, coordinator of communal works, and –in some cases– owner of the lands. The chief or lord had a court, his activity was ruled by strict protocol and he was the main player in a complex public ritual.

The colossal heads were the representation of the chieftains or lords with their power attributes, the ancestors turned into stone that granted with their presence the legitimate and sacred character of the ruling governors. Apparently, the colossal heads in San Lorenzo were placed following two axis running from north to south in the central part of the site. The dominant theme in Olmeca monumental sculpture was that of adult men belonging to the governing class as represented in the colossal heads, the sitting characters and the thrones. Olmeca art is closely linked to the building of power during the emergence of the hereditary social inequity. This means the basin of river Coatzacoalcos was the starting point of aboriginal America on its way to civilization, the state and social classes. Once San Lorenzo’s prime was over, the axis was first moved to La Venta and then to Tres Zapotes. In 300 B.C. the Olmeca people and their art had already disappeared.

The exhibition of the colossal Olmeca head from San Lorenzo (Veracruz) in Fundación Proa brings about concepts other than those of an archaic art and their load of ideological meaning surrounding power at the dawn of an urban society. Exhibited now in the hall of a XIXth century building that was made into an art center, the Olmeca stone head takes on a new meaning within the categories of modern art and appears as an antecedent of Botero’s work or the sculptures by the Argentinean Claudio Barragán. Thus, in Buenos Aires, Head Number 9 becomes our contemporary. However, if exhibited in the context of a nationalistic XXth century museography, it serves to announce –from its pre-Columbine magnificence– the emancipation of peasantry as well as it props up that identity proposed by the national State.

After all, they are all options of heritage and they are valid as soon as each context creates its own observer and shapes the meanings.

LECTURAS

Clark, John (coordinador). [1994]. Los olmecas en Mesoamérica. El Equilibrista y Turner Libros, Madrid-México.

Covarrubias, Miguel. 1980. El sur de México. Instituto Nacional Indigenista. México D. F.

De la Fuente, Beatriz, 1975. La cabezas colosales olmecas. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México D. F.

López Austin, Alfredo y López Luján, Leonardo. 1996. El pasado indígena. El Colegio de México - Fondo de Cultura Económica. México D. F.

Paz, Octavio. 1994. “El arte de México: materia y sentido”. Obras completas. Los privilegios de la vista II. Arte de México; tomo 7. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México D. F.

![]()

Las culturas prehispánicas de la costa del Golfo de México

Por Dr. Rubén B. Morante López (fragmento). * Curador de la muestra “La magia de la risa y el juego en el arte prehispánico de Veracruz, México. Arqueología mexicana, 1200 a.C. - 900 d.C.”.

Es el Director del Museo de Antropología de Xalapa.

Mesoamérica es un área ecológica y cultural que comprende casi la totalidad de Centroamérica y aproximadamente la mitad de México. Es un territorio apto para la agricultura y está limitado al norte por las zonas desérticas y al sur por las otrora inexpugnables selvas del Darién. Con desarrollos en diferentes períodos de la época precolombina, en esta amplia área se han delimitado cinco zonas culturales: el occidente y el centro de México, Oaxaca, la región maya y la costa del Golfo de México. A esta última nos referiremos de manera particular ya que allí florecieron, a lo largo de más de tres mil años, muchas culturas locales entre las que se destacan las que identificamos como olmeca, del centro-norte y del centro-sur de Veracruz, y huaxteca”.

Magia de la risa y el juego en el Veracruz prehispánico

Uno de los aspectos más característicos del pasado prehispánico de Veracruz, lo constituye la representación de la risa en piezas maestras denominadas figurillas o caritas sonrientes. La diversidad de expresiones relacionadas con la sonrisa que representan estas obras, les otorga un lugar en la historia del arte universal. Ya lo había dicho Octavio Paz (…): “...la rica variedad de expresiones risueñas, a mi juicio, sin paralelo en la historia entera de las artes plásticas”. Los tocados de los personajes muestran una gran diversidad de motivos en los cuales se plasma un mensaje relacionado con la visión del mundo y la religiosidad del antiguo pueblo que habitó la parte oriental de México, antes de la llegada de los conquistadores europeos.

En las costas del Golfo de México, lo lúdico en relación con la risa se complementa con la presencia de juguetes y objetos que recrean escenas de personajes que juegan. La manifestación llamada risa, a pesar de parecernos muy humana, en muchas obras plásticas va más allá de lo humano. Este gesto denota sentimientos primitivos que han prevalecido en todas las etapas de la historia y que son similares en todos los hombres. Sin embargo, la valoración y el significado que cada pueblo y cada sociedad otorgó a la risa varía, y por ello debe considerarse en los contextos del tiempo y del espacio.

A pesar del rompimiento que Octavio Paz (…) menciona entre el pueblo olmeca y los posteriores escultores de imágenes sonrientes, al parecer el origen de la representación plástica de la risa en América se encuentra precisamente en esculturas tempranas, concretamente en la Cabeza Colosal 9 de San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan, Veracruz, cuya antigüedad data de entre el 1200 y el 900 a.C.

Los rostros sonrientes de la costa del Golfo de México

Alfonso Medellín Zenil (…) afirma que hacia principios de la década de 1950 ya se conocía un centenar de extraordinarios ejemplares de esculturas sonrientes que provenían de la subárea cultural que denominó Río Blanco-Papaloapan. En 1950 había realizado sus primeros hallazgos in situ en Remojadas, Veracruz, y posteriormente exploró los sitios de Los Cerros y Dicha Tuerta (1953) y Nopiloa (1957-58) hallando más de 1500 figurillas que trasladó al Museo de Antropología de Xalapa.

En 1972 se descubrieron en El Zapotal (…) decenas de entierros secundarios, muchos de ellos acompañados de figurillas sonrientes. Recientemente, (…) se las ha encontrado muy cerca de las fuentes del río Atoyac. El sitio arqueológico más cercano es el de Toro Prieto y se ha datado para el Clásico Tardío. Como sucedió con otros objetos, entre ellos yugos y vasijas, al parecer estas figuras sonrientes se depositaban en el agua como ofrendas. En cuanto a la época en que se elaboraron, todos los sitios arqueológicos corresponden al período Clásico. Sin embargo, la producción más abundante data del Clásico Tardío (600 a 900 d.C.) durante el apogeo del arte y la cultura en la subregión Centro-Sur de Veracruz; por tanto no es extraño que en esa época se produjeran en mayor número y calidad obras de todo tipo.

Los artesanos

Cuando examinamos las figuras sonrientes cuya procedencia ha podido ser constatada, observamos que existen evidentes cambios de estilo que corresponden no solo a la temporalidad, sino a diversas áreas culturales dentro de la región que hemos delimitado como productora de estas esculturas.

Alteraciones corporales

La mutilación dentaria solo se encuentra en algunas sonrientes y en más del 90% de los ejemplares que la presentan, consiste en el limado de los incisivos laterales y los caninos, tanto superiores como inferiores, para resaltar los incisivos centrales. En ocasiones esta mutilación se combinó con otra que consiste en el limado en diagonal de los incisivos centrales. Si bien todas las figuras sonrientes evidencian deformación craneana, esta puede variar: la gran mayoría muestra una acusada deformación tabular oblicua, sin embargo en algunos casos la forma de la cabeza parece indicar una deformación tabular erecta y en otros el llamado tipo zapotal. Estos últimos son los menos, ya que sobre todo aparecen en las sonrientes que yacen sobre las llamadas “camas de deformación” a las cuales se sujetaba a los infantes durante el proceso de deformación, que se realizaba mediante bandas que fijaban la cabeza sobre las tablas de la cama. La deformación tabular se lograba con la aplicación de tablas sobre dos planos de compresión: uno anterior, sobre el frontal y otro posterior, abarcando parcial (erecta) o totalmente (oblicua) el occipital. Entre ambos se deformaban los parietales y los temporales, dando al cráneo una forma ancha y plana.

Los tocados

Medellín Zenil (1986) se basó en los tocados para establecer una tipología de las sonrientes. Ello no es extraño, ya que como la mayoría de las cabezas sonrientes se encuentran separadas de sus cuerpos y presentan rasgos físicos muy similares, lo que se hacía evidente era la muy rica variedad de tocados. Estamos por tanto ante la clasificación más utilizada e importante de estas figurillas. Cabe destacar que hay esculturas sonrientes sin tocado, que muestran el cráneo sin pelo o con tan solo un par de mechones, a las que Medellín denominó “tipo lisa” y gracias a ellas sabemos que los tocados se ajustaban perfectamente a la forma del cráneo.

Para nosotros, los tocados pueden clasificarse en siete tipos:

Liso: Se trata del más sencillo ya que carece de motivos, aunque algunas veces presenta perforaciones que pudieron servir para incrustar algunos elementos como plumas o cabellos.

Con mechones: Aunque los mechones de cabellos se encuentran combinados con otros tocados y siempre presentes en las sonrientes femeninas, hay tocados lisos que tienen solo algún mechón aislado, aun cuando se trate de figuras masculinas. También pueden presentarse en pares o aislados.

Con entrelaces: Consiste en dos bandas que se cruzan. Este tocado es el más abundante entre las sonrientes. Ello no es extraño ya que en toda la costa del Golfo de México el símbolo de los entrelaces fue muy popular durante el Clásico. A la variante más común Medellín (1987, 102) la denomina “geométrico lateral” y en ella encuentra tres subtipos, en una el signo aparece en posición vertical, en otra horizontal y en la tercera se combina con la figura de un pelícano. No obstante lo anterior, existe una variedad muy amplia de entrelaces en los tocados de las sonrientes, algunas de ellas de gran elegancia.

Con vírgulas: Este es el segundo símbolo más común entre la decoración de las sonrientes. Medellín (1987, 101) encuentra 7 subtipos, pero no los define. El estilo que él (p. 118) determina como decadente y denomina “Dicha Tuerta” tiene, aparte de los “picos”, una vírgula en el tocado.

Geométricos: Dos son los símbolos más importantes en este tocado: el Xicalcoliuhqui y la doble voluta (Medellín 1987, 117). Esta podría confundirse con la doble vírgula, sin embargo en este caso estamos ante volutas unidas. El Xicalcoliuhqui se presenta también invertido.

Zoomorfos: Los más atractivos tocados son sin lugar a dudas los que tienen formas de animales, entre ellos monos, garzas o pelícanos, peces, renacuajos, saurios y serpientes. En algunos las imágenes se combinan en escenas: las aves atrapan peces o renacuajos, o los monos parecen haber sido sacrificados mediante la extracción del corazón.

Antropomorfos: Los hombres solo aparecen en un tipo de tocado, en complejas escenas míticas donde su rostro de perfil se combina con sendas cabezas de serpiente, entrelaces y signos vegetales.

Atavíos

En cuanto a la vestimenta, el atavío más típico de los hombres era el maxtlatl (taparrabo). Existía además una prenda muy original que Medellín (1987, 89) consideró exclusiva de los hombres y a la cual llamó “faja pectoral”. Las mujeres usaban faldas, enredos, huipil (túnica) y quechquemitl (blusa abierta). De la mayoría de las esculturas sonrientes que estudiamos (más del 90 %) ha llegado a nosotros la cabeza o el cuerpo separados, sin que pudiesen ser vinculados. Por lo general es en los cuerpos donde se puede determinar el sexo, no obstante, las cabezas sonrientes poseen elementos que permiten establecer el género, ya que el peinado parece haber sido distinto para hombres y para mujeres. Los niños y los hombres no presentan cabellos y sus cabezas son de forma semitriangular. Las mujeres, en cambio, tienen dos largos mechones a ambos lados, los cuales hacen ver su cabeza un tanto rectangular.

Una serie de atavíos estuvieron destinados para ambos sexos: orejeras, pulseras, tobilleras y collares. Todas las imágenes aparecen descalzas. En cuanto a las orejeras, tienen forma de aro, espiral, pétalo, flor o con un simple orificio para insertar un pendiente.

Retratos o estereotipos físicos

La gran mayoría de las sonrientes presentan nariz recta y fina, labios delgados, boca pequeña, ojos rasgados, pómulos salientes y barbilla angulada. Incluso cuando no poseen pupilas, podemos suponer que tenían estrabismo. Son pocos los individuos obesos representados.

En las sonrientes cobra un papel fundamental la deformación craneana y la mutilación dentaria. Se trata sin duda de estereotipos físicos que se relacionaban con una idea muy particular de la belleza. Hay figuras que denotan un gran individualismo, lo que llevó a algunos estudiosos como Spinden (1922) a considerarlas retratos, en virtud de la diversidad de tocados y rasgos físicos que presentaban. Sin embrago, las subsecuentes exploraciones sacaron a luz talleres completos donde se las fabricaba con moldes. Dentro de esa repetición, encontramos muchos tipos físicos diferentes aunque siempre correspondientes a un mismo patrón. Algunos artistas trataron de diferenciar su obra añadiendo elementos personales que denotan una gran creatividad: lo realizaban en sus moldes, mediante aplicaciones al pastillaje en los atavíos y en la pintura del cuerpo y del rostro. Además debemos destacar la riqueza y variedad de sonrisas en estas imágenes de terracota.

Hombres, dioses y hombres dioses

Doris Heiden (…) afirma que las “...sonrientes representaban a las semejanzas de los dioses más que a los dioses mismos...”. Algunas recrean claras escenas de la vida diaria: personajes que cargan bebés y a los mismos bebés gateando o recostados en una cama. En este sentido, no podemos atribuirles un carácter divino. Sin embargo, estas figuras muestran una clara referencia a las deidades en la vida diaria e incluso se han registrado figuras de Tlaloc y Xipe Totec sonriendo.

Epílogo

Hablar de la risa es siempre difícil porque el gesto es dual. Asimismo, las ideas de inframundo y maldad que tenían los pueblos de Mesoamérica siempre serán complicadas para nosotros, ya que no se corresponden con los conceptos occidentales. No creo que la risa abierta en las sonrientes se refiera a un aspecto malévolo y que la risa ligera se relacione con la bondad. Ambas se presentan en estas figuras y no existe un contexto específico para cada tipo de risa.

Mesoamerica is both an ecological and cultural area which comprises almost all of Central America and about a half of the Mexican country. It's a soil apt to be cultivated, bound to the north by the desert areas and to the south by the once impenetrable Darién Jungles. Though flourishing at different times during the pre-Columbian era, five different cultures have been outstanding –the one situated in the West of Mexico; another one in the Center of Mexico, Oaxaca; the Maya area, and that on the Coast of the Mexican Gulf. We will deal with the last one in particular. This area was, for over three thousand years, a territory where many local cultures flourished. We shall mention the Olmeca one, the one in the southern center of Veracruz, that of the northern center of Veracruz, and the Huaxteca one. Each shall be briefly dealt with in the following paragraphs.

Laugh and games: their magic in prehispanic veracruz

One of the most outstanding aspects of the pre-historic past of Veracruz can be found in some figurines or smiling small faces, real masterpieces that represent the act of laughing. The expressions and diversity related to smiling, as shown in these works, placed them in the history of universal art. Octavio Paz (1971, 17) had already stated that: “...the rich variety of smiling expressions knows no parallel in the entire history of fine arts”. The headpieces of the characters portrayed show a rich variety of motives in which a message can be read –this is one related to the specific viewpoint in the conception of the world and the religious spirit these ancient peoples in the western part of Mexico possessed before the coming of the Spanish conquerors.

The playfulness of the act of smiling as depicted in these works is complemented in the Mexican Gulf coasts with the existence of toys and objects where scenes of characters playing are recreated. The natural act of laughing appears in these art pieces as something which transcends what is merely human. In fact, it is an attitude revealing those primitive feelings that have prevailed throughout the stages of history and are common to all men. And even so, the value and meaning assigned by each society to the act of laughing varies and needs to be seen within context set in time and space.

Even when Octavio Paz (1971, 15) mentions the breach between the Olmeca people and the subsequent sculptors of smiling images, the apparent origin of the artistic representation of laugh in America should be found in the early sculptures –in particular, the Cabeza Colosal 9 (Gigantic Head) in San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan, Veracruz– dated between 1200 to 900 B.C.

Alfonso Medellín (see Paz, 1971, 41) states that by the early 1950s over a hundred samples of smiling sculptures were publicly known, and these came from the sub-cultural area he has designated Rio Blanco-Papaloapan. It was in 1050 that he made his first findings in situ , in Remojadas, Veracruz. After that, he learned about other sites, Los Cerros and Dicha Tuerta, which he explored in 1953, and Nopiloa (1957-58). He found over 1500 figurines of the kind which he later took to the Museo de Antropología, in Xalapa.

In 1972 there was a new finding in El Zapotal (Torres et al., 1973) and he learned about it because there had also been previous plundering of the site. This place was one with scores of secondary burials and many of them were surrounded by smiling figurines. More recently (Archaeologist Fernando Mirando, personal comment, June 1997) more smiling figures have been found in the Atoyac river, near its source. The nearest archaeological site is that of Toro Prieto and it has been dated as belonging to the Late Classical period. As it happened with other objects, such as yokes and vessels, the smiling figures were thrown into the water as offerings. As to the time they were carved, all the archeological sites point to the same period, the Late Classical, that is (600 to 900 A.D.) This meant the acme of art and culture in the sub-region of south central Veracruz and consequently this explains why a great number of art pieces of all kinds and of the best quality were produced during this period.

The artisans

When we examine those smiling figures whose origin is clear, we are able to see there are noticeable changes in style. These correspond not only to the time they were made but also to a certain cultural area within the region we have marked as producer of those sculptures.

Body alterations

The alteration of the teeth is visible in some “sonrientes”. And when this was so, it was of the A4 or the B4 type. Over a 90% of the displayed samples show an alteration of the A4 type and this means the filing of both the upper and lower lateral incisors and the canines, so as to set off the central incisors. Even when all the smiling figures show skull alteration, this can vary. For the major part, there is the slanting tabular deformation. However, in some cases, the head seems to have undergone a straight tabular deformation. And there are fewer samples which exhibit the type called “zapotal” –a deformation that appears in those smiling figures that lie on the so-called “deformation beds” (these were beds to which infants were tied to and, through the use of bands, were meant to keep the child's head pressed to the beams). The tabular deformation was achieved through the use of boards on the two areas of compression: an anterior one, stuck to the frontal bone and a posterior one, stuck partially (for an erect deformation) or totally (for a slanting deformation) to the occipital bone. Between these compression elements, the parietal and the temporal bones were deformed, thus causing a head characterized by its wide and flat shape.

The headpieces

Medellín (1986) established a typology of “sonrientes” using their headpieces as a basis. Having a great number of “cabezas sonrientes” (smiling heads) separated from their bodies and all of them with similar physical features, it is not strange that he focused in the rich variety of headpieces. This is, then, the most important and widely used of any of the classifications ever made regarding these figurines. There are smiling figures that have no headpiece on, they exhibit a bald head or this has only one of two tufts –Medellin has classified them as “tipo liso” (plain, unadorned type). The existence of these plain heads led us to realize their headpieces was perfectly adapted to the shape of the heads. In our opinion, headpieces can be of seven types:

Plain. This is the simplest kind of headpiece since it is un-patterned –even when some have a few small holes that might have been used to stud elements such as feathers or hairs.

With tufts . Even when the tufts of hair are combined with other headpieces and are always present in the smiling women, there are plain headpieces that have some isolated tuft (even in the case of masculine figures). Tufts of hair can be found either in pairs or alone.

Intertwined. This is two intertwined bands. This headpiece is most common among the “sonrientes”. This is no strange fact since during the Classical period, the symbol of the intertwines was very popular in all the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. The most common variant is named “lateral geometric” by Medellín (1987, 102). In fact, he finds there are three subtypes –one has a vertical sign, the second has a horizontal sign, and the third is combined with the shape of a pelican. Besides all this, we find a wide variety of intertwines in the headpieces of the “sonrientes”, and some of them are remarkably smart.

With small rods or sticks. This is the second commonest symbol in the ornamentation of the “sonrientes”. Medellín (1987, 101) finds 7 subtypes though he does not define them. The style he himself (p 118) defines as decadent and names it “Dicha Tuerta” has, between the “beaks”, a small rod in the headpiece.

Geometric . Two symbols are essentially important in this headpiece –the Xicalcoliuhqui and the double volute (Medellín 1987, 117). The double volute could be taken for the double rod, yet in this case we have linked volutes. The Xicalcoliuhqui appears also in an inverted position.

Zoomorphic . No doubt the most attractive headpieces are those that have animal shapes such as monkeys, herons, pelicans, fish, tadpoles, sauria, and snakes. Some of them show scenes where the birds are catching fish or tadpoles, others show monkeys sacrificed through the plucking out of their hearts.

Anthropomorphic. Men appear in only one type of headpiece. Their profiles, as part of complex mythical scenes, are combined with several snake heads, intertwines, and vegetal signs.

Arrays

As regards clothing, the most typical array for men is the maxtlatl . There is also a very original piece Medellín (1987, 89) calls “ chest belt ” and this he considered was exclusively used by men. Women wore skirts, “enredos”, huipil and quechquemitl. Over a 90% of the smiling sculptures we studied are either heads or bodies –a fact that prevented us from making the right matches. Generally, gender can be told out of the bodies. However, gender can apparently be determined in the case of the smiling heads through the hairstyles of men and women. Children and men are represented without hair and their heads look semi-triangular. Women, on the other hand, are shown with two long tufts of hair on both sides, and this makes their head look a bit rectangular. A number of elements were meant both for men and women: earpieces, bracelets, ankle rings, and necklaces. All the images are barefooted. Earpieces may be in the shape of rings, volutes, petals, flowers or just like a piercing to wear a drop earring.

Portraits or physical stereotypes

A great number of the “sonrientes” have a straight, thin nose, thin lips, a small mouth, slanting eyes, protruding cheeks, and an angled chin. Even when their pupils are not represented, we infer these people were cross-eyed. Few obese individuals are represented. Skull deformation and teeth alteration play an essential role in the “sonrientes”. These undoubtedly are physical stereotypes that had a very particular conception of beauty. Of course there are figures imbued of great individualism –in fact some scholars like Spinden (1922) considered them to be portraits, having in mind the diversity of headpieces and physical features they present. Subsequent exploration revealed entire workshops where they were fabricated using moulds. Within the repeated models, we find many different physical types, though they are all in the same pattern. Some artists tried to differentiate their work adding personal elements that denote great creativity. They did it on the cast figures, using clay paste for the garments and paint for body and face. These terra cotta images must also be noted for the richness and the variety of their smiling.

Men, gods, and semi-gods

Octavio Paz (1971, 17) holds laugh is both human and divine. The “sonrientes” are “ Dancing creatures who seem to celebrate the sun and incipient nature... ” and they are also associated to deities who later, in the Altiplano, will be called Xochipillio (1 Flower) and Macuilxóchitl (5 Flower). Doris Heiden (1970, 61) maintains that “... the sonrientes were meant to represent likenesses of the gods rather than the gods themselves ”. Some “sonrientes” clearly show images of everyday life –women carrying babies and babies toddling or lying in bed. In this sense, we cannot give them a divine character. But what really counts is they give us images of daily life, as we have a clear allusion to deities and even the presence of one or two deities smiling –these are Tlaloc and Xipe Totec. The reference to Macuilxóchitl-Xochipilli signaled by Medellín (1987,97) we deem undeniable.

Epilogue

Laugh is difficult to speak of since it is a dual gesture. Concepts like underworld and evil will always be complex to grasp in the Mesoamerican peoples since they do not correspond with the western concepts. I believe that the open smile in the “sonrientes” cannot be referred to an evil aspect or that their slight smile has to do with kindness. Both are present in these figures and there is no specific context for each kind of laugh. Both are related to the pre-Hispanic under world and this has nothing to do with Christian hell. Death itself, in the context of the “sonrientes” does not necessarily purport the ominous character the western culture assigns to it.