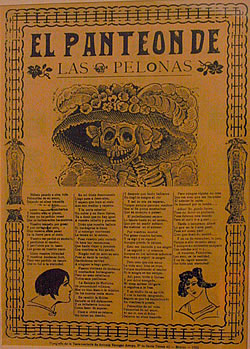

Grabado

Jose Guadalupe Posada

Colección Museo Mural Diego Rivera

José Guadalupe Posada

Estos grabados de José Guadalupe Posada, tienen la finalidad de ejemplificar el sentido dramático pero irónico con el que representó a la muerte, característica siempre presente en la cultura mexicana.

Aquí podemos ver la imagen original de La catrina, que Diego Rivera también representa.

Posada fue un excelente grabador en metal, en su fructífera vida creadora fue perseguido y atacado, debido a que siempre enfatizó su temática haciendo crítica y denuncia de atrocidades e injusticias cometidas por los regímenes que gobernaban el país.

Se considera que dejó una obra aproximada de veinte mil grabados. La gran mayoría de ellos los realizó gracias al trabajo conjunto que emprendió con el también célebre impresor Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, sería casi imposible concebir el trabajo de uno sin el otro.

José Guadalupe Posada es sin duda uno de los personajes emblemáticos del arte mexicano.

JOSÉ GUADALUPE POSADA

Por Diego Rivera

En México han existido siempre dos corrientes de producción de arte verdaderamente distintas, una de valores positivos y otra de calidades negativas, simiesca y colonial, que tiene como base la imitación de modelos extranjeros para proveer a la demanda de una burguesía incapaz, que fracasó siempre en sus intentos de crear una economía nacional y que ha concluído por entregarse incondicionalmente al poder imperialista.

La otra corriente, la positiva, ha sido obra del pueblo, y engloba el total de la producción, pura y rica, de lo que se ha dado en llamar "arte popular". Esta corriente comprende también la obra de los artistas que han llegado a personalizarse, pero que han vivido, sentido, trabajado expresando la aspiración de las masas productoras. De estos artistas el más grande es, sin duda, José Guadalupe Posada, el grabador de genio.

Posada, tan grande como Goya o Callot, fue un creador de una riqueza inagotable, producía como un manantial de agua hirviente.

Posada, intérprete del dolor, la alegría y la aspiración angustiosa del pueblo de México, hizo más de quince mil grabados; así lo asegura el editor Vanegas Arroyo.

Mano de obrero, armada de un buril de acero, hirió el metal ayudado por el ácido corrosivo para arrojar los apóstrofes más agudos contra los explotadores.

Precursor de Flores Magón, Zapata y Santanón, guerrillero de hojas volantes y heróicos periódicos de oposición.

Ilustrador de los cuentos y las historias, las canciones y las plegarias de la gente pobre. Combatiente tenaz, burlón y feroz; bueno como el pan y amigo de divertirse, cuyo reducto fue un humilde taller instalado en una puerta cochera, a la vista, pero al flanco de la iglesia de Santa Inés y de la Academia de San Carlos.

¿Quiénes levantarán el monumento a Posada? Aquellos que realizarán un día la Revolución, los obreros y campesinos de México.

Posada fue tan grande, que quizá un día se olvide su nombre. Está tan integrado al alma popular de México, que tal vez se vuelva enteramente abstracto; pero hoy su obra y su vida trascienden (sin que ninguno de ellos lo sepa), a las venas de los artistas jóvenes mexicanos cuyas obras brotan como flores en un campo primaveral, después de 1923.

La producción de Posada, libre hasta de la sombra de una imitación, tiene un acento mexicano puro.

Analizando la labor de Posada, puede realizarse el análisis completo de la vida social del pueblo de México.

Los valores plásticos que contiene la obra de Posada son todos los más esenciales y permanentes de la obra de arte.

La composición de Posada, de un extraño dinamismo, mantiene, sin embargo, el equilibrio más grande de los claros y oscuros en relación a la superficie del grabado.

El equilibrio a la par que el movimiento, es la calidad máxima del arte clásico mexicano; es decir, el pre-cortesiano.

Del arte clásico mexicano es propio también el amor al carácter y el empleo, a la vez terrible y drolático, de la muerte, convertida en elemento plástico.

Posada: la muerte que se volvió calavera, que pelea, se emborracha, llora y baila.

La muerte familiar, la muerte que se transforma en figura de cartón articulada y que se mueve tirando de un cordón.

La muerte como calavera de azúcar, la muerte para engolosinar a los niños, mientras los grandes pelean y caen fusilados, o ahorcados penden de una cuerda.

La muerte parrandera que baila en los fandangos y nos acompaña a llorar el hueso en los cementerios, comiendo mole o bebiendo pulque junto a las tumbas de nuestros difuntos..

La muerte que es, en todo caso, un excelente tema para producir masas contrastadas de blanco y negro, volúmenes recientemente acusados y expresar movimientos bien definidos de largos cilindroides formando bellos ángulos en la composición, magistral utilización de los huesos mondos.

Todos son calaveras, desde los gatos y garbanceras, hasta Don Porfirio y Zapata, pasando por todos los rancheros, artesanos y catrines, sin olvidar a los obreros, campesinos y hasta los gachupines.

Seguramente, ninguna burguesía ha tenido tan mala suerte como la mexicana, por haber tenido como relator justiciero de sus modos, acciones y andanzas, al grabador genial e incomparable Guadalupe Posada.

Su buril agudo no dio cuartel ni a ricos ni a pobres; a estos les señaló sus debilidades con simpatía, y a los otros, con cada grabado les arrojó a la cara el vitriolo que corroyó el metal en que Posada creó su obra.

La distribución de blancos y negros, la inflexión de la línea, la proporción, todo en Posada le es propio, y por su calidad lo mantiene en el rango, de los más grandes.

Porque Posada fue un clásico, no le subyugó nunca la realidad fotográfica, la infrarealidad, siempre supo expresar como valores plásticos la calidad y la cantidad de las cosas dentro de la super-realidad del orden plástico.

Si es indiscutible lo que dijo Augusto Renoir: que la obra de arte se caracteriza por ser "indefinible e inimitable," podemos decir que la obra de Posada es la obra de arte por excelencia. Ninguno imitará a Posada; ninguno definirá a Posada. Su obra, por su forma, es toda la plástica; por su contenido es toda la vida, cosas que no pueden encerrarse dentro de la miserable gaveta de una definición.

These engravings of Jose Guadalupe Posada, have the purpose of exemplifying the dramatic but ironic sense in which he represented the death, always present in the Mexican culture. Here we can see the original image of the Catrina, that Diego Rivera also represents. Posada was an excellent metal engraver, in his fruitful creative life he was persecuted and attacked, because he always emphasized the critic and denunciation of atrocities and injustices committed by the regimes that governed the country. It is considered that he left a work approximated of twenty thousand engravings. The majority of them were made together with the famous printer Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, it would be almost impossible to conceive the work of one of them without the other. Jose Guadalupe Posada is without a doubt one of the emblematic personages of the Mexican art.

JOSÉ GUADALUPE POSADA

by Diego Rivera

In Mexico two truely different currents of art production have always existed, one of positive values and another one of negative qualities, the colonial, that has as it bases the imitation of foreign models to provide the demand of an incapable bourgeoisie, that always failed in its attempts to create a national economy and that has concluded giving itself unconditionally to the imperialistic power. The other current, the positive one, has been the work of the people, and includes the total of the production, pure and rich, of the so-called "popular art". This current also includes the work of the artists who have reached to personalize themselves, but that has lived, felt, worked expressing the aspiration of the producing masses. The greatest artist of these group is, without a doubt, Jose Guadalupe Posada.

Posada, as great as Goya or Callot, was a creator of an inexhaustible wealth, he produced like a boiling water spring. Posada, interpreter of the pain, the joy and the distressing aspiration of the people of Mexico, did more than fifteen thousand engravings; thus it assures the publisher Vanegas Arroyo. Hand of worker, armed with a steel burin, hurt the metal helped by corrosive acid to throw the acute apostrophes against the orerators. Precursor of Flores Magón, Zapata and Santanón, fighter of flying papers and heroic newspapers of opposition. Illustrator of stories and histories, the songs and the prayers of the poor people. Tenacious, mocking and ferocious combatant; good like the bread and friend of amusing himself, he worked in a humble factory installed in a door garage, at sight, but to the flank of the church of Santa Ines and the Academy of San Carlos.

Who have raised the monument to Posada? Those that will make one day the Revolution, the workers and farmers of Mexico. Posada was so great, that perhaps one day his name will be forgot. He is integrated to the popular soul of Mexico, that perhaps he becomes entirely abstract; but today his work and his life extend (even if they don't know it), to the veins of the Mexican young artists whose works appear like flowers in a primaveral field, after 1923. The production of Posada, free even of the shade of an imitation, has a pure Mexican accent. Analyzing the work of Posada, a complete analysis of the social life of the people of Mexico can be made. The plastic values that the work of Posada contains are the most essential and permanent ones of the art work. The composition of Posada, of a strange dynamism, maintains, nevertheless, the greatest balance of clear and darks in relation to the surface of the engraving. The balance and the movement, is the maximum quality of the Mexican Classical Art; that is to say, the pre-cortesian.

Of the Mexican Classical Art he is own also the love to the character and the use of the death, turned into plastic element. Posada: the death that became skull, that fights, cries and dances. The familiar death, the death that becomes an articulated cardboard figure and that it is moved throwing of a cord. The death as a sugar skull, the death to sweeten the children, while the adults fight and fall shot, or hangs of a cord. The death that dances in the fandangos and accompanies us to cry the bone in the cemeteries, eating mole or drinking pulque next to the tombs of our deceaseds. The death that is, in any case, an excellent subject to produce contrasted masses in black and white, volumes recently accused and to express movements defined by cylindrical lengths forming beautiful angles in the composition, skillful use of the clean bones. All are skulls, from the cats and garbanceras, to Don Porfirio and Zapata, all the orderlies, craftsmen and catrines, without forgetting the workers, farmers and the gachupines. Surely, no bourgeoisie has had so bad luck as the Mexican, because it had in the brilliant recorder and incomparable Guadalupe Posada, the relator of its ways, actions and fates. Its acute burin gave no chance neither to rich nor to poor men; to these he indicated to these their weaknesses with affection, and to the others, with each engraving he threw to their face the glass that corroded the metal in which Posada created his work. The distribution of white and black, the flexion of the line, the proportion, everything in Posada belongs to him, and by his quality he maintains himself as a Master. Because Posada was a classic, he was never subjugated by the photographic reality, the infrareality, he always knew how to express like plastic values the quality and the amount of the things within the super-reality of the plastic order. If it is unquestionable what August Renoir said: that the art work is characterized being "indefinable and inimitable", we can say that the work of Posada is the art work par excellence. Noone will imitate Posada; noone will define Posada. His work, by its form, is all the plastic thing; by his content it is all the life, things that cannot be locked in within the miserable frame of a definition.