Pica Pica, Bajada Cordón

An exhibition on the Buenos Aires sidewalk

By Martín Huberman

The fabric that characterizes the City of Buenos Aires, whose layout originates from Spanish treaties for colonial dominion, established the block as the fundamental cell in the urban conquest of the territory. In this basic constitution of cellular urbanity, the core would be primarily intended to house everything that defines the realm of the private, structuring a practical space for domesticity and other programmatic offshoots that define life behind closed doors. Outside that core, everything would be of a public nature—an untamed and hostile territory—where infrastructures would be located to project the city to another scale, creating an evolutionary and undoubtedly functional system.

To protect and nourish the habitable core, the system would provide a cellular membrane, whose fundamental action would be to mediate interrelations between the outside and the inside, the public and the private, and especially among inhabitants, embracing the human scale as a foundation and aesthetic principle. This membrane would take the forms of what we now call the sidewalk.

The sidewalk is above all the first public space, where countless intermediations between technical, civic, and individual domains unfold. As a technocratic organism, it is where infrastructures of all kinds are distributed—some visible in aerial systems and others hidden in underground networks—serving, connecting, integrating, draining, or discharging much of the necessary foundations for the development of our urban being in a covert and silent manner. As a social structure, it is on the sidewalk that much of our civic acts occur, condensing neighborhood relationships, professional interactions, and even interspecies connections, which give true character and density to our city.

At the scale of our social contract as urbanites, what defines us more as citizens: the care of our homes or our sidewalks? Is it possible that, in those scarce three linear meters, from curb to facade, we can represent our true urban idiosyncrasy? And consequently, can we define the urbanity we truly deserve through the study of our sidewalks? This exhibition presents a catalog of observations from a heterodox group of professionals who spent time with their heads down, in thoughtful gesture, searching in our sidewalks for identity traits, experimenting with the specificity of urban identity construction from our sidewalks.

A joyful sidewalk

From Pica Pica onward, sidewalks can be considered a canvas for urban interpretation and appropriation in a façade-oriented key. The sidewalk of Fundación Proa, in particular, is a clear example of the rich constellation of performative possibilities that the sidewalks of Buenos Aires can offer. Its uniqueness lies in its façade-oriented approach with institutional rigor, mediating between the classic definitions of public space through art.

Over the years, a unique history of interventions designed by local and international artists and architects has been created, paying tribute to the public and communicative potential of the sidewalk through artistic, spatial, performative, and educational reinterpretations. This space has hosted nomadic schools, oversized mother spiders, Borgesian labyrinths, fashion parades, and a unique performative façade culture in the city. It has served as a support, record, and stage to accommodate audiences eager for artistic experiences that deepen their interpretation of the city.

From its inception, the institution has made the management of its first public space a unique and resonant case for the memory of the neighborhood, its residents, and the entire city, which nostalgically recalls it through the personal and popular experiences that it has inspired.

100 years of sidewalks Works by Horacio Coppola and Facundo de Zuviría

In the realm of simple gestures that go almost unnoticed in our daily lives, the sidewalk evokes a garden of records related to the libertine expression of its inhabitants, defining a compositional aesthetic spectrum that is neighborhood-oriented, pedestrian, animal, poetic, residual, and vegetal. The evolution of the city is reflected in the record of its sidewalks, and this is evident through the lens of Horacio Coppola and Facundo de Zuviría, who have made it their subject of study. From covered sidewalks in arcades that shelter passersby to sidewalks that provide refuge for the homeless, the historical record of the first 20 centimeters of a city that has verticalized at a frenetic pace over the last 100 years is essential for understanding it as a living organism that needs to be grounded in the public realm to articulate its spasmodic growth.

The first sidewalk Works by Iván Breyter, Marcos Zimmermann, and Fernando Schapochnik

On the eastern edge of the city, bordering the river and illuminated by the morning sun in horizontal pampas, the first sidewalk of the city develops. This edge, which demarcates water and territory, has evolved since the consolidation of Buenos Aires as an autonomous territory, driven by progress moving inward along the river in a human-centered gesture. Over time, this sidewalk crystallized as a fundamental gesture in the relationship with the Río de la Plata, both in hedonistic terms and within the field of urban water infrastructure. Its nominal width was defined by Sunday strolls, its height by a prudent distance from the water due to bathing prohibitions, and its balustrades by the need for resilience against storm surges and tides dictated by the river.

Borde este is a systemic record by architect Ivan Breyter, who traverses the coastline of Buenos Aires, compiling an aesthetic history of the relationship between sidewalk and balustrade, transforming the river into a façade composed of improbable relationships.

In times of storms, when the Sudestada reigns and flooding becomes common, this sidewalk shifts from a point of observation to the horizon to a stage for abrupt breakwaters caused by the river's abundant waves. Marcos Zimmermann's work captures this brutal confrontation between nature and artifice, redefining the formal conditions of both the coastal defense and the low neighborhoods affected by the water.

In low neighborhoods like La Boca and the banks of the Riachuelo, it is common to walk along uneven sidewalks that have sought to provide informal responses to the flooding that disrupts daily life. Vereda pólder, the record by Fernando Schapochnik, subtly describes the ingenuity of some residents in addressing the torment of rising water, turning their own sidewalk into the last bastion of defense against flooding.

The non-sidewalk

Works by Cristóbal Palma

The sidewalk is for the city a system of urban connection, not only in pedestrian or vehicular terms (in conjunction with the street) but specifically at the infrastructural level. Generally, where the sidewalk reaches, services follow, bringing with them the notion of urban infrastructure that defines its formality. In the city's popular neighborhoods, where urbanization programs work diligently on the processes of ordering and expanding informal networks, the arrival of the sidewalk symbolizes the reconfiguration of growth, appropriation, and ordering logics.

In his photo essay Construcción, Villa 31, Chilean photographer Cristóbal Palma sets out to document the urban particularities of one of the city’s most dynamic informal neighborhoods. The absence of sidewalks in this segment of his record highlights their organizing power within urban systematology; their disappearance transforms the interstitial spaces between built structures into an absolute field for outdoor life, in all its forms, but especially in terms of unregulated appropriation rich with possibilities.

Sidewalk culture

Works by Ignacio Coló and Grupo Bondi

For the residents of this city, the sidewalk is the first space of public appropriation, where their urban character is uniquely forged. Perhaps this is due to the foundational law that complicates the control of our sidewalks in public realms but with private management, making them a primary stage for countless urban appropriations.

Ignacio Coló's series Carritos typifies a piece of that local idiosyncrasy that turns sidewalks into promenades, in this case a riverside one linked to gastronomy. The carts, informal barbecues that have taken shape on the sidewalks of Costanera Sur, perfectly complemented the centennial promenade project designed by engineer Benito Carrasco.

In a similar vein, the Parrichango by Grupo Bondi systematizes the culinary appropriation of sidewalks through transitory and semi-public barbecues, subtly transforming a shopping cart into a portable grill.

Sidewalk Code

Works from the Plan Visual de Buenos Aires by Gonzalez Ruiz - Shakespear and RRAA.-

In the urban liturgy of Buenos Aires, overflowing with a myriad of linguistic mechanisms that organize and signal our city life, the signs of Pica Pica, Bajada Cordón stand out from the regulated norm. Primarily due to the informality of their handwritten strokes and especially for the precise and enigmatic nature of their haiku poetry, whose sound derives from the work of a bricklayer.

The work of RRAA.- (displayed on the sidewalk of PROA21) finds its foundation in those linguistic opportunities offered by the street. Their interventions blend with unused signs, appropriations of light poles, and a certain character of anonymous vigilance, reclaiming the power of words amid chaos.

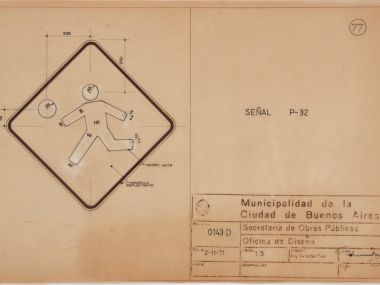

The Plan Visual de Buenos Aires (Visual Plan for Buenos Aires) (1971-1972), designed by Ronald Shakespear and Guillermo González Ruiz, represents the first formal effort to regulate the information chaos that inhabits the sidewalks of Buenos Aires, generating a comprehensive plan for urban signage in the city. The design systematized and mechanized the necessary guidelines for the proper habitability of the streets while poetically integrating the torrid relationship of the city with the Río de la Plata, the Pampean streams, and water.

All sidewalk

Works by Daniela Mac Adden and Pedro Ignacio Yañez

Central Area, beginning in the 1970s with the pedestrianization of Calle Florida and peaking in recent decades with the Planes Microcentro (Microcentro Plans), Prioridad Peatón (Pedestrian Priority) y Calles Verdes (Green Streets) initiatives. During these years, a marked transition occurred from the traditional system of streets in the central area to a hybrid system of coexistence between cars and pedestrians, effectively eliminating those first twenty centimeters of urbanity.

These plans successfully removed bus lines from small streets to the avenues, leveling roadways with sidewalks, which were then widened to prioritize pedestrians. The last link in this chain, the program Calles Verdes, explores a series of solutions addressing the new reality of the Central Area, which experienced significant hollowing out after the pandemic, with an uncertain future that seems to be shifting from a characteristic business hub to a neighborhood of mixed-use programs.

The diptych composed of the works by Daniela Mac Adden and Pedro Ignacio Yañez focuses on the iconic building of the former Banco de Londres, designed by architect Clorindo Testa, specifically at the emblematic corner of Reconquista and Bartolomé Mitre, where architecture appears to provide refuge on an urban scale. Here, the sidewalks are perforated with drainage systems, where vegetation promises a future of shade, oxygenation, and drainage to mitigate the effects of urban heat islands.

Sidewalk habitat Works by Martín Simonyan and Estudio Cabeza

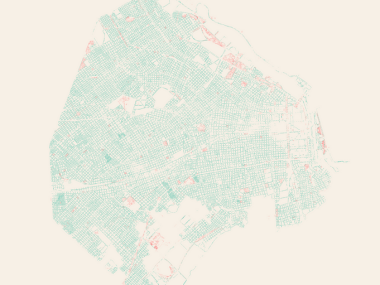

Sidewalks function as systems composed of urban infrastructures, with sanitary, signage, lighting, and drainage being the most evident. However, there is another crucial aspect for our times: the ecosystemic. Sidewalks serve as the primary home for the public tree canopy in Buenos Aires, with seven times the volume of species planted in public parks.

This fact, resulting from research by landscape architect Martin Simonyan, highlights sidewalks as the main stage for the city’s plant life. From this perspective, they can be interpreted as one of the primary systems for mitigating heat waves, providing shade in summer and serving as a fundamental axis for the proliferation of animal species that cohabit the territory in the canopies of their trees.

It is essential to raise awareness about the plant identity of the city, recognizing and promoting species that are native to the territory prior to urbanization. His research notes that the top four species planted on sidewalks include exotic species such as the American Ash (with 141,826 specimens), the Plane Tree (with 34,786 specimens), and the Paradise Tree (with 24,561 specimens). However, perhaps the most notable case is that of the Ficus (with 23,909 specimens), which has never been part of a formal urban planting program by the city. Its presence on sidewalks is linked to a process of appropriation, where the transition from inside homes to sidewalks was informally executed by local residents.

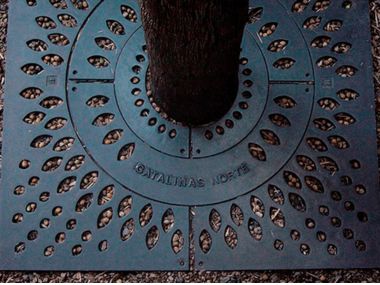

In a protective spirit, both for the tree beds and the pedestrians who traverse them, the series of tree pits designed by Diana Cabeza and Estudio Cabeza acknowledges the importance of sheltering the main inhabitants of our sidewalks: the trees. Their design simultaneously recognizes the need for adaptability to respect the growth rhythms of trunks, and their materialization in cast steel reflects an ancestral tradition of sidewalk management, where drains that directed the city’s water back to the river were once forged.

Horacio Coppola

Esto es Buenos Aires, 1931/2024

Archivo Horacio Coppola. Cortesía Galería Jorge Mara - La Ruche

Horacio Coppola used to walk around Buenos Aires neighborhoods —especially Palermo— with Jorge Luis Borges and painter Alfredo Guttero. On one of these walks, Borges stopped to look at the reflection of trees and houses on a puddle in the cobbled street. He stared at it for a long moment and exclaimed: “This is Buenos Aires!” Coppola then took his camera, snapped a photo, and titled the image after Borges’ exclamation: Esto es Buenos Aires (This is Buenos Aires).

Puerto, 1931

Calle Corrientes 3060, 1931

The photographs exhibited by Horacio Coppola are part of a selection made by Facundo de Zuviría for the book Buenos Aires. Coppola + Zuviría, featuring images of the city taken by these two photographers in the 1930s and 1980s. These images open a dialogue between eras, styles, and an urban reality that has evolved over the years. They reveal the unique perspective of these two renowned Argentine photographers, who developed a close connection with Buenos Aires in their work. Coppola’s works describe the 1930s from an avant-garde perspective, focusing on the imposing architecture through some of the most surprising and captivating shots ever taken of the city.

Iván Breyter

Serie Borde Este, 2024

Cortesía del artista

Borde Este is a systemic record by architect Ivan Breyter that explores the coast of Buenos Aires, documenting the aesthetic history of the relationship between sidewalk and balustrade, transforming the river into a façade composed of improbable connections.

Diana Cabeza

Protector Hojitas redondo con crecimiento, 2024

Cortesía Estudio Cabeza

This protector features detachable rings designed to be removed as the tree grows. It is made of sandblasted cast iron with special black paint for casting. Designed to protect trees, it also offers the option to incorporate an iso-logo, reinforcing the institutional image. It is used on sidewalks and in public or institutional planters.

Ignacio Coló

Serie Carritos, 2012

Cortesía del artista

The Carritos series is a photographic project capturing life and the urban landscape of Buenos Aires' waterfront, focusing on the food carts that populate this area. Through his lens, Coló documents both the aesthetics of these spaces and the human interactions within them. The images reflect local culture, the social life of the waterfront sidewalks, and a traditional commercial activity of the city. This series not only pays tribute to the city's outdoor dining culture but also reflects on public space and its significance in citizens' lives.

Daniela Mac Adden

Banco # 3, 2024

De la serie Edificios dormidos

Cortesía de la artista

Edificios dormidos is a series of photographs capturing buildings at rest, when they are “asleep” from their intended use. The images are taken exclusively in natural light, highlighting the quiet atmosphere and the subtle interaction between architecture and its surroundings. Through this technique, the relationship between space and time is emphasized, showing how buildings acquire a new presence in the stillness, away from human activity.

Facundo de Zuviría

La City, Reconquista y Bartolomé Mitre, 2001

Casa de Chapas y arbolito,1986

Peatones en la Recova del Bajo, 1995

Crisis, Centro Sur, 1986

The photographs selected by Facundo de Zuviría for the book Buenos Aires. Coppola + Zuviría establish a dialogue with Coppola’s from a more contemporary and urban vision. They depict shops, storefronts, streets, and representative characters of Buenos Aires in recent decades. These are two distinct yet complementary perspectives on the day and night, the streets and shops, the events, and the customs of Buenos Aires. Coppola has imprinted some archetypal images in the visual memory of the Argentine capital. Facundo de Zuviría, his disciple and follower, did the same almost five decades later, following in his master's footsteps.

Guillermo González Ruiz y Ronald Shakespear

Planos de señalética del Plan Visual de Buenos Aires, 1971-1973/2024

Fondo Guillermo González Ruiz. Fundación IDA, Investigación en Diseño Argentino

The Visual Plan of Buenos Aires, designed by Guillermo González Ruiz and Ronald Shakespear in the 1970s, aimed to improve visual communication within the urban space. This comprehensive plan established a signage system that facilitated navigation and reinforced the city's visual identity. It included signage for streets and public spaces, considering both functionality and cultural context. Over time, the plan has become a lasting reference in the urban design of Buenos Aires.

Taxi Stop, c. 1971. Urban Signage (School Children Warning Sign), c. 1973

The signage designed by the González Ruiz - Shakespear studio has become a true icon of Buenos Aires. These pieces, adapted over time, are designed in a systematic and predictable manner. Free of advertising on their informational surfaces, they are easily recognizable from any angle, making them highly visible to both pedestrians and drivers. With decades of history, the signage is part of the urban heritage and is deeply ingrained in the collective memory of Buenos Aires residents.

In particular, the taxi stop sign was conceived with the same constructive logic as the rest of the program but with greater freedom in its design. This sign evokes the everyday act of hailing a taxi, using a color palette that distinctly refers to Buenos Aires taxis.

Guillermo González Ruiz Archive. Fundación IDA, Research in Argentine Design.

Grupo Bondi

Parrichango, 2015

Fondo Grupo Bondi. Fundación IDA, Investigación en Diseño Argentino

The Parrichango is a reinterpretation of the shopping cart, designed as a portable grill. This project embraces cultural aspects of Argentine society, famous for its asados, and its political and social history, such as the supermarket looting during the 2001 crisis.

The structure is made from a single 1.5 mm thick sheet of laser-cut metal, allowing for easy and accessible manufacturing. Grupo Bondi provides the cutting file, suppliers, and downloadable instructions on their website, promoting the democratization of design and the use of local materials. This approach combines functionality and culture, celebrating Argentina’s grilling tradition in a creative way.

Martín Simonyan

Arbolado público de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, 2024

Cortesía del artista

A map of public trees on sidewalks and green spaces, based on publicly available information from the City of Buenos Aires Government data portal and the collaborative website ArboladoUrbano.com.

Cristóbal Palma

Serie Villa 31, 2019-2020/2024

Cortesía del artista

The photographs in this series document life in one of Buenos Aires' most emblematic villas miseria (shantytowns). Cristóbal Palma captures the complexity of its urban fabric and the lives of its residents. The images offer an intimate and authentic perspective on life in the neighborhood, capturing the distinctive characteristics of its people and environment. This documentation was completed before the COVID-19 pandemic and aims to portray Villa 31’s conditions before impending changes.

Fernando Schapochnik

Vereda Pólder, 2024

Cortesía del artista

Vereda Pólder is a series of four photographs exploring the urban and social aspects of the raised sidewalks in Buenos Aires' La Boca neighborhood. Unlike other parts of the city, where sidewalks are generally no higher than twenty centimeters, some sidewalks in La Boca rise above the roofs of cars. This unique feature emerged mainly as an informal response to the recurring floods that plagued the area since Buenos Aires was founded in 1536, inundating homes and businesses. Although infrastructure improvements have since controlled flooding, La Boca's raised sidewalks remain as relics of another era.

Pedro Ignacio Yañez

Serie Calles Verdes, 2023

Cortesía del artista

The photographs in this series portray interventions by the Urban Landscape Secretariat on the sidewalks of Buenos Aires. They are part of the book Paisaje de Buenos Aires. Regeneración urbana 2012-2023, which compiles the work done by the City of Buenos Aires' Urban Landscape Subsecretariat during this period. These images highlight the integration of nature and urban infrastructure, emphasizing the importance of trees and green spaces for urban life.

Marcos Zimmermann

Sudestada. Costanera Norte, Buenos Aires, 1994

Balaustrada. Costanera Norte, Buenos Aires, 1993

Inundaciones. La Boca, Buenos Aires, 1993

Cortesía del artista

The essay Río de la Plata, río de los sueños was created between 1991 and 1994, with the eponymous book published in 1994. The photographs capture the essence of the Río de la Plata, emphasizing the relationship between the natural landscape and urban identity.

The images showcase the interaction between nature and architecture, revealing the fragility of urban elements in the face of nature’s power. This perspective on the urban landscape of Buenos Aires presents the balustrade as a boundary and a point of interaction between the river and the city. The compositions emphasize linearity and perspective, highlighting the contrast between the rigidity of architectural structures and the unpredictability of nature.