Gallery 1

Women: work force and political resource

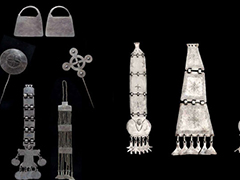

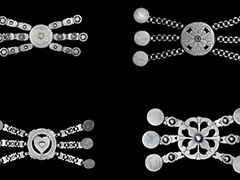

Las Pampas exhibition departs from the figure of women, ornaments and jewellery design. The wives of the leading Caciques (political chief), who had settled in these territories during the 19th Century, were of great importance and recognition, because through their ornamentation, their delicate and subtle silver jewels, created the economic and political power symbol of the Cacique.

The pieces on exhibition have a diverse and unique design. They were handmade by highly professionalized craftsmen that took part of an active economy. The jeweller created outstanding pieces were the sound of the piece created by the woman’s movement was music that translated into alliance and seduction.

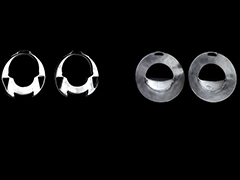

The women embellished different part of their bodies with numerous jewels: around their head, neck and chest. This ensemble presents an image of luxury and power. The chosen part of the body was greatly accentuated when the women was on a horse and the movement generated a sensual sound. Although they are mostly silver, some pieces were produced with found coins, coloured glass beats and industrial drilled thimbles, among other materials.

Carlos Aldunate remarks: “Although the possession of silver elements appears as common denominator of every women’s trousseau in the 19th Century, there is no doubt that these pieces were in the hands of the most important lonko or caciques (…). Travellers (…) describe the never-ending processions of women that were behind the chiefs during ceremonies and public official functions, whose pectorals, brooches, necklaces, head pieces, braid ribbons and bells, all silver, produced a great spectacle and sound that made pronounce the German words “It was a Chinese style music band of a military regiment” (Treutler 1861) […]

“(…) Some travellers insinuate that the way women use certain garments, such as ‘four to six fingers wide silver rings … in the arms and legs under the calf’ was a sign of their virginity (Treuler 1861).” Jewels accompanied the diseased woman in her grave: “Eugenio Robles (1942), tells the story of a woman’s funeral (…) where ‘one of her relatives placed both hands on the pit, holding a great part of the diseased jewels.’”

The women, for whom significant monetary amounts were paid, constituted – as well as captives and children- the main work force: domestic work, family attendance, care of the flock, water and firewood supply, harvest, knitting, and yarn spinning were their main duties. Women tanned leather, made household equipment and wooden tools and carried her belongings. Each cacique had many women. All of them lived together and took care of the household while the chief rode his horse through the Pampas.

The custom of embellishment shared by women continues until today, specially during celebrations and special ceremonies.

Bibliography:

- Aldunate del Solar, Carlos. Reflexiones acerca de la platería mapuche, Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino. http://www.precolombino.cl/preco_upl/pdf/18/1.pdf

- Caraballo de Quentin, Claudia. De los metales precolombinos a la platería pampa

- Pereda, Teresa. La platería en las tierras del este y del oeste

Gallery 2

Social space and political territory

In this gallery, an assembly of everyday life pieces and objects account for the customs of the native settlers in the pampas. The pieces, manufactured in leather, wood and stone, demonstrate the diversity of daily life activity in the 19th Century tolderías (tent settlement).

Raúl Mandrini states in Los pueblos originarios de las regiones meridionales en el siglo XIX (Native settlers in the meridian regions during the 19th Century): “The toldería was […] the central space of aboriginal social life. […] Life in the tolderías was supported by an active domestic and rural economy. This is where one can perceive the impact of the long-term exposure to Creole society and the inclusion of Mapuche and European elements. Around these toldos (tents), sheepherding in a small or medium scale provided food for the families as well as different commodities, mainly leather and wool […]. The tolderías were an important center of craftsmanship, which, besides covering local needs, provided remnants for exchange”.

The set of ponchos placed in circle at the center of the gallery emulates the way in which assemblies and parliaments -spaces of discussion and the political platform for each community- were organized. Mandrini explains: “The traditional institutions characteristic of the native’s political life were the assemblies, committees or parliaments, in which all the conas, or men of the spears, took part. The supreme power resided, at first, in these institutions, and they decided on crucial affairs, devoted to the great caciques (chiefs) and solved issues related to peace and war. […] In mid 19th Century, they were already the center of political life and their authority and influence exceeded traditional warrior functions. In fact, although they lacked the formal apparatus- written laws, public force and an administrative department- the great caciques, whose increasing authority was consolidated by the prestige of their bloodline and the number of conas they were able to mobilize, exerted a crucial influence in fundamental decisions and assembly resolutions. […]

The wealth of each Cacique consisted of wife trade, which implied political alliances with other bloodlines; liquor trade and permanent feasts for guests; supporting close friends and family, whether native or white, who used to live alongside him, and carried out different tasks by accompanying him in the malones (Indian raids) and assemblies.

The more generous the caciques, the greater their prestige and authority regarding their followers, whose support was essential when taking decisions in the parliaments, where they had to demonstrate their will power and authority”.

Bibliography:

- Raúl Mandrini, Los pueblos originarios de las regiones meridionales en el siglo XIX

Gallery 3

The horse: Travel, commerce and power

The diversity and sophistication of riding crops, wide belts, knives, stirrups and headstalls demonstrate the prominence of the horse in 19th Century Pampa. The custom of ornamentation highlighted the power and development the horse brought to a territory where, before its arrival, inhabitants traveled the vast plains on foot.

“[…] one thing is the Indian on foot, whom we know of because of the first chroniclers; another is the Indian with a horse. The native settler of the pampas was the one who better resisted conquest attempts. The cause of this was not solely his indomitable nature, his courage, his greed and his ability to become accustomed to the landscape. The true cause was that the Indian of the pampas was an Indian on a horse. He was a rider. And what a rider and what horses!” states Alvaro Yunque in the prologue to Fronteras y Territorios de las Pampas del Sur (Frontiers and territories from the South of the pampas), of Alvaro Barros.

Lucio V. Mansilla wrote in Una excursión a los indios ranqueles (An expedition to the Ranquel Indians), published in 1870: “The horse of the Indian is unique. It was trained in a way that combined tameness, strength and speed, which made him unbeatable […]. We believed that the extraordinary characteristics of this animal were due, in a large extent, to the particular respect that the Indian felt for him [...]. It was, above all, his friend. Around it, he created a true culture, in which the use of silver was deeply involved”.

This friendship typified the image of the pampas, and the horse reached a status of his own: “Horse’s bones and teeth were part of grave goods […] while, in other parts of America, people lived surrounded by Chinese silk and porcelains”, comments Ruth Corcuera in Herencia textil andina (Textile Inheritance of the Andes).

This gallery displays silver pieces used by caciques to lustily decorate their horses, and manufactured by the same goldsmiths that worked their wives’ jewelry. Silversmiths in Argentinean and Chilean Patagonia designed different patters, some floral, and others with less ornamentation.

The horse and the woman indicated -depending on their ornamentation- the cacique’s status and hierarchy. A cacique riding his horse on the plain, covered in his jewels and followed by a numerous group of women, with the sound and sparkle of their silverwork, seemed to be a common striking image narrated by the chroniclers of the pampas.

The horse and silverwork modified the landscape and enabled commerce with the Creole world. As Raúl Mandrini refers to in Los pueblos originarios de las regiones meridionales en el siglo XIX (The native settlers of the meridian regions of the pampas): “The relation between both societies, which had known moment of extreme violence and periods of relative peace, had an impact on the lives of native settlers by introducing new products, goods, unknown economic, social and political practices, other beliefs and ways of thinking to their customs, which were soon incorporated and adapted to their interests and life conditions [...] native settlers transformed their economy, their sociopolitical organization and their belief system.”

Bibliography:

- Claudia Caraballo de Quentin, De los metales precolombinos a la platería pampa

- Ruth Corcuera, Herencia textil andina, Fund. CEPPA, Buenos Aires, 2010

- Raúl Mandrini, Los pueblos originarios de las regiones meridionales en el siglo XIX

- Lucio V. Mansilla, Una excursión a los indios ranqueles, Buenos Aires, 1870. http://es.wikisource.org/wiki/Una_excursión_a_los_indios_ranqueles

Gallery 4

The poncho

José de San Martín, Lucio V. Mansilla and cacique (chief) Calfucurá were three historical figures and three Ponchos (hand-woven piece of clothing) marked by the depths of time. These ponchos –as well as a numerous set of pieces from private collections- constitute the this gallery. The room, devoted to the most characteristic element of the plain, has on display Pehuenche, Pampa and Ranquel pieces, hand-woven with wool, as well as some English manufactured ponchos produced in woolen cloth.

The poncho given to general San Martín during the crossing of the Andes - courtesy of the Museo Histórico Nacional -; a poncho given by Ranquel cacique Mariano Rosas to general Mansilla –mentioned in the novel Una excursión a los indios ranqueles (An expedition into Ranquel Indians)– and the poncho owned by the great cacique Calfucurá - courtesy of the Museo Gauchesco Ricardo Güiraldes - constitute the frame of reference for a comprehensive tour of colors, patterns and designs characteristic of the garment essential in the social dynamics of the 19th Century.

–Have this, brother; wear it in my name. It was made by my “queen wife”.

I accepted the gift, which had a great meaning, and returned the gesture by giving him my rubber poncho.

While receiving it he said:

–If ever we are not at peace, my Indians shall not kill you, brother, because of this poncho.

–Brother –I answered–: if ever we are not at peace and we meet again, I shall find you, because of this piece.

The great meaning of Mariano Rosas’s poncho was not that it could be a shield when in danger, but that the poncho knitted by a man’s queen wife was, amongst the Indians, a sign of love, like a wedding ring for the Christians.

When I got out of the tent and was seen with the cacique’s poncho, an expression of surprise aroused in all the physiognomies.

People from the palace were more attentive and solicitous than ever. Pour humanity!

Lucio V. Mansilla, Una excursión a los indios ranqueles, cap. 58.

The poncho is a simple and elegant garment for men, handmade by his spouse. It covers the basic need of warmth, while still enabling free movement. It is the permanent and faithful companion of the pampas inhabitant. Ponchos are described in several travelers’ testimonies. In 1760, Dom Pernetty, states: "In regards to how people were dressed [...], they wear a sort of striped garment, with different colored bounds (listas), with a unique slit in the middle in order to pass their head. This coat falls over shoulders covering the body up to the fists, falling to the front and back at knee-length; and with fringes around the edges; they are called ponchos”. These testimonies talk about the great size and striped pattern that characterized this type of clothing, as they were first used by gauchos. Painter and traveler E. E. Vidal (1820) writes that, in Peru and Salta, “the manufacture of ponchos is famous; they were made out of cotton, highly priced and of great beauty; however, those executed by the humble Indians from the pampas were made of wool, closely-woven, and strong, so as to resist heavy rain. The way they were decorated was intriguing and original, the colors were moderate but long lasting; although they have dyes with brighter color, they use them for other purposes”.

“In the beginning of the 19th Century, the poncho was present in the preparation of the liberating campaigns. During the time of the independence, the expeditionary armies of Ortiz de Ocampo to Alto Perú, of Belgrano to Paraguay (and afterwards to the north), and to the Andes, passed by populations that lived in the countryside, received persistent donations in reales (Spanish currency), horses, mules, blankets, goat fur and mainly ponchos” asserted Ruth Corcuera in Herencia textil andina (Textile Inheritance of the Andes).

England was the big textile manufacturer of the time and exported cotton yarn, wool and diverse fabrics for the making of suits and dresses. The English manufactured poncho was a wanted piece, specially by the Indians, who traded many handmade ponchos, of great craft value, for one industrially made, whose use was widely spread. Even though some of these ponchos reproduced floral designs traditional of the Victorian era, the majority of the patters were strange to the English tradition. Manufactured for the local market, they included an enormous range of earth and night sky colors: slender representations of ñandu feathers, cloaks with images of bobcats, suns, stars, moons, thunderbolts, and designs called “ojo de perdiz” (eye of a quail), “grecas” (girdles with repeating pattern) and “guardas” (vertical design pattern).

The poncho patria, also manufactured in England, had a collar and a slit that was buttoned up in the chest. It is a possible adaptation of similar military Spanish cloaks, which military authorities gave the caciques. Their use was also very popular.

Federico Bárbara states in Usos y costumbres de los indios pampas (Uses and habits of the Pampa Indians) (1856): “Women had the indispensable obligation to spin the yard and knit in order to dress their husband, on top of providing fabric for their sons.”

Bibliography:

- Clara M. Abal de Russo, Arte textil incaico, Fund. CEPPA, Buenos Aires, 2010

- Ruth Corcuera, Herencia textil andina, Fund. CEPPA, Buenos Aires, 2010

- Ruth Corcuera, Diseños y colores en la llanura

- Juan Carlos Garavaglia, “El poncho: una historia multiétnica” en Guillaume Boccara (ed.), Colonización, resistencia y mestizaje en las Américas

(siglos XVI-XX). IFEA / Abya-Yala, Quito, 2002

- Lucio V. Mansilla, Una excursión a los indios ranqueles, Buenos Aires, 1870. http://es.wikisource.org/wiki/Una_excursi%C3%B3n_a_los_indios_ranqueles