Interview with Julian Rosefeldt (extract)

By Sarah Tutton and Justin Paton

To give visible action to words

Anna-Catharina Gebbers and Udo Kittelmann

Huesos Dada

Paul Auster

Manifiestos argentinos. Políticas de lo visual 1900-2000

Rafael Cippolini

Manifesting the Manifesto: Why One Genre Has Been Ignored

Leslie Heme

The Manifesto. Negotiating Reality

Nanna Katrine Bisbjerg

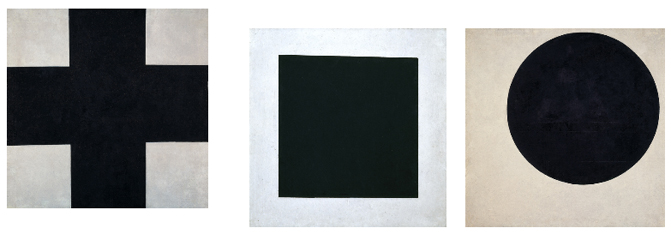

Movimientos: Futurismo; Vorticismo; Jinete Azul; Expresionismo Abstracto

Movimientos: Estridentismo; Creacionismo; Suprematismo

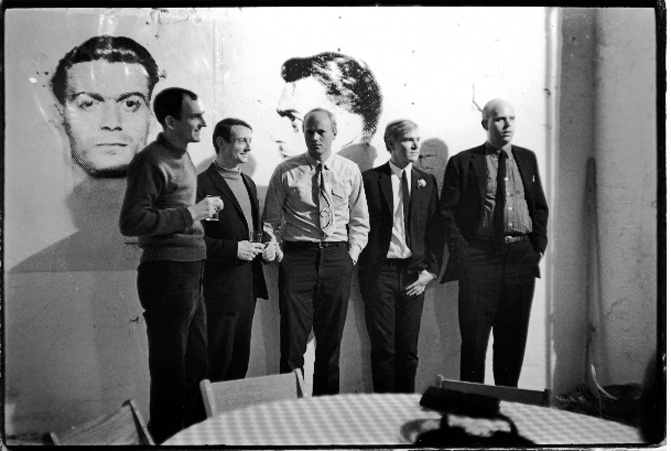

Movimientos: Pop Art; Merz; Fluxus; Conceptualismo

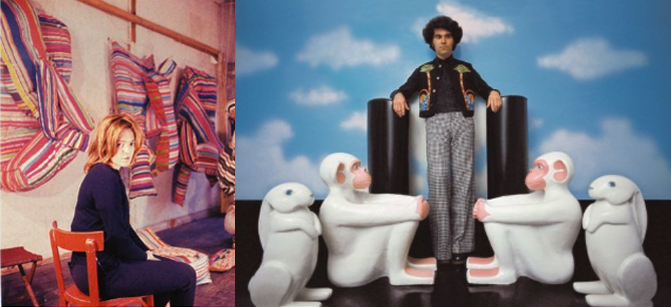

Julian Rosefeldt Ph: Veronika Bures

Julian Rosefeldt Ph: Veronika Bures

Interview with Julian Rosefeldt (extract)

By Sarah Tutton and Justin Paton

In: JULIAN ROSEFELDT: MANIFESTO, Koening Books, 2016

‘Manifesto’ is a word with a lot of historical weight. What does it mean to you?

I have used the title Manifesto as a clear statement that the focus in this work is above all on texts, whether by visual artists, filmmakers, writers, performers or architects – and on the poetry of these texts. Manifesto is an homage to the beauty of artists’ manifestos – a manifesto of manifestos.

Were manifestos important to you as a young artist?

No, I must admit that they were not important to me in the past. I simply didn’t know them at the time. Today I think of the manifesto as a rite of passage, not only for young artists but also for young people in general. As we move beyond adolescence, we leave home and scream out our newly discovered fury at the world. A manifesto often represents the voice of a young generation, confronted with a world they don’t agree with and they want to go against. You can either play in a punk band, start yelling at your parents or your teachers – or you can write or make art. Art historians tend to regard everything created and written by artists with reverence and respect, as if, from day one, the artists themselves intended their work to become part of art history. But we shouldn’t forget that these texts were usually written by very young men who had barely left home when they reached for the pen. Thus their manifestos are not only texts which are intended to turn art – and eventually the whole world – upside down and revolutionise it; at the same time they are testimonials about the search for identity, shouted out into the world with great insecurity. So I read the artist’s manifesto firstly as an expression of defiant youth, then as literature, as poetry – so to say, Sturm und Drang remastered.

The texts you have selected come largely from the first half of the last century. Why?

Yes, most of the manifestos that I have included in Manifesto are from the European avant-garde in the early twentieth century, with others from the neoavant-garde in the 1960s. The art scene at the beginning of the last century was still very small and those writers of art manifestos were again a minority within this tiny art scene. To be heard, artists needed to yell. The art scene today is a global network and business with diverse means of expression. The manifesto as a medium of artistic articulation has become less relevant in a globalized art world. You could say that the interview, the podium discussion, the talk show, the dialectically led discourse have replaced the former loud bellowing sole claim of the manifesto. It would sound unnecessarily exaggerated and almost romantic, even a bit ridiculous, to shout ‘Down with…’ or something similar today. Still, there are a few very interesting contemporary manifestos – as, for instance, the Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics (2013) by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams or the feminist Cyborg Manifesto (1991) by Donna Haraway – but they read more like socio-economical and -political analysis. Yet when you read a manifesto from the 1920s or even the 1960s, you still hear that original voice, that fervent desire to propel an idea into the world.

Was there a particular text that sparked your interest?

My interest in the artist’s manifesto began whilst I was working on Deep Gold in 2013. Deep Gold is an homage to Luis Buñuel’s film L’Age d’Or about two young lovers and the obstacles that prevent them from consummating their relationship. For Buñuel the lover’s predicament symbolizes the hypocrisy of bourgeois interview with julian rosefeldt Sarah Tutton and Justin Paton 97 –– Manifesto –– society, Catholicism and traditional family mores. During my research I was reading a lot about gender and feminist theory, and eventually about manifestos by feminist artists. I came across two texts by the Futurist poet and choreographer Valentine de SaintPoint. She lived an interesting life; she started out as a strong Futurist, later sympathised with fascism as did many of her Italian artist friends, and died in Egypt as a Muslim. She wrote two manifestos, one called Futurist Manifesto of Lust (1913) and the other Manifesto of the Futurist Woman (1912). They are both published in a book called 100 Artists’ Manifestos [2011, edited by Alex Danchev] which became an important source for Manifesto. When I was young I had studied – probably like everybody interested in art – Dada, Fluxus, the Surrealists and the Futurists, but only superficially. Now, during my research for Manifesto, when I read any manifesto I could find including those related to theatre, dance, film and architecture, it was exciting to discover that the same ideas appear again and again. And these common ideas all came along with so much energy – that very young, wild energy. The writing was beautiful, and I could hear the words as if they were spoken. I realised that they weren’t just historical art documents, but the most lively, performable text material. They reminded me rather of a piece of theatre, of a Sarah Kane or Frank Wedekind text or something comparable. And so I began to imagine these manifestos in performed scenes.

According to what criteria did you seek out and put together the twelve manifesto collages you created?

Before I started writing the script and collaging the manifestos, the development of the work involved a lot of textual research and analysis. With the exception of a fragment quoted from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s Manifesto of the Communist Party of 1848, ‘All that is solid melts into air’, my selection begins at the start of the twentieth century with the legendary 1909 The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and ends shortly after the turn of the century. I included Karl Marx, because for me his is the mother of all manifestos – besides the Ten Commandments and the Lutheran Thesis. The most current manifesto I used is the Golden Rules of Filmmaking (2004) by the American film director Jim Jarmusch. From all of the manifesto authors I read, I subjectively chose about sixty whose manifestos I found to be the most fascinating, and also the most recitable. Or I chose them because they suited one another. For example, the comments of Vasily Kandinsky and Franz Marc correspond extremely well with the thoughts of Barnett Newman. And also the texts of André Breton and Lucio Fontana could be linked, while the writings of the many Dada or Fluxus artists could be combined into a kind of condensation, a kind of Super-Dada- or Super-Fluxus-Manifesto. Through cuts and the combination of original texts from numerous manifestos, twelve manifesto collages finally emerged. And these read harmoniously within each collage to a degree that the borderlines between the text fragments could no longer be identified. I have constructed Manifesto as a series of episodes that can be seen separately but that can also be seen together in their entirety, as a choir of different voices. In this sense Manifesto became a new text itself – again: a manifesto of manifestos.

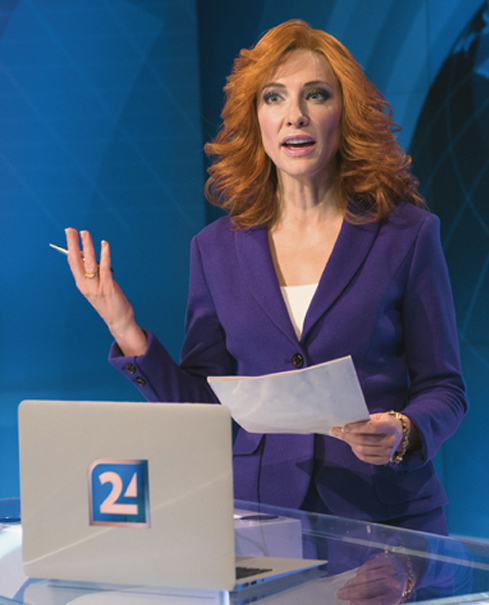

You have an extraordinary collaborator in all this, the actor Cate Blanchett. She inhabits thirteen different roles set against twelve different scenarios. How did these characters and their dialogue evolve?

The main idea for Manifesto was not to illustrate the particular manifesto texts, but rather to allow Cate to embody the manifestos. Until the last third of the twentieth century there were only a few manifestos written by women artists. Most were written by men and they are just bursting with testosterone. So I thought it was thrilling to let them be spoken today by a woman. The process of scripting Manifesto was very organic. I started to play with the texts and to edit, combine and rearrange them into new texts that could be spoken and performed. I like to imagine these texts as the words of a bunch of friends sitting around a table in a bar talking and arguing. They are complementing each other in a playful way. One may say ‘Down with this or that…’ and the other replies, ‘Yes, to hell with…’ I would take a sentence by one artist and interrupt it with the words of another one. Sometimes they would fit perfectly. The words took on a new energy when combined, and if you start to read the text like that it also becomes more vivid and more speakable. While in one way the process of collaging them together was maybe not very respectful to the original texts, in another I liked the way that it referenced this idea of a collection of voices, a conversation. Many of the early manifestos, of the Futurists and the Surrealists, were written by groups of artists. There were already multiple voices in these texts. I then rearranged these multiple voices from different manifestos into new monologues: in this way the authors talk to one another while, at the same time, they are addressing the audience with one homogeneous voice. In parallel, I began to sketch different scenes in which a woman talks in monologue, ending up with sixty short scenes, situations right across various educational levels and professional milieus. The only thing these draft scenes had in common was that they are being performed today, and that a woman is holding 98 –– Manifesto –– a monologue: whether a speaker by a grave at a cemetery, a primary-school teacher in front of her class, or a homeless person on the street. Sometimes we listen to the woman’s inner voice; in other instances she addresses an audience; once she even interviews herself, etc. I finally edited everything down to twelve scenes and twelve corresponding text collages. A thirteenth collage was used for the introductory film, in which we see a burning fuse in extreme slow motion. Those words that remained were simply the most beautiful, speakable and performable ones.

Manifesto was filmed over a twelve-day period in Berlin in the winter of 2014. Was there any room for improvisation?

Usually there is, but since this time we were working within a very tight time frame there wasn’t much space for improvisation. Just to give you some context, for an arthouse film you normally produce three to five minutes a day. We had to produce twelve minutes a day, which is pretty similar to the timeframe of a TV soap opera. But of course we didn’t want to work on the aesthetic level of a TV soap. So we needed a very generous team and most of all a very generous actor to work under these conditions. One challenge was the huge amount of text to be spoken in twelve different accents which Cate had to overcome. And then each of the characters had to speak in a milieu represented by the colour of speech. As if this weren’t enough, for organisational shooting reasons sometimes we even had to cover two roles per day, which also meant an additional costume and makeup change each day for Cate and the hair and makeup team. For these reasons and given the tight time schedule we had to plan the shoot meticulously. But, here and there, a certain amount of spontaneity and improvisation was necessary. And of course Cate might have read the text or understood the respective scene differently from me, and so sometimes she surprised me with ideas emerging from the depths of her profound experience and incredible talent. Every day was different, like entering Wonderland, encountering an entirely new world and character. And the way that the dialogue – or better, monologue – shaped the scene was constantly shifting and exciting. And despite the highest level of concentration and dedication, and the many working hours each day, Cate admirably retained her very special sense of humour during work. We laughed a lot.

Humour plays an important role in your work, and there is a lot of humour and absurdity in Manifesto.

It’s very difficult to purposefully create humour – as humour rather derives from spontaneity. To place a good joke in a film, the timing has to be good, and the acting as well; the absurd logic in the scene has to be convincing. Everything has to come together in that one moment, and that’s very difficult to achieve. For me, the humour in Manifesto stems from the combination of the spoken word and the scenario itself. The interaction of certain images with text fragments happened intuitively. And I find some of them funny, although it isn’t my main intention to make the audience laugh. For instance, the Pop Art scene. If you read a Pop Art manifesto you might at first come up with the idea that we need something ‘pop’, and that we might need a ‘pop’ world in which to read that manifesto. But I thought, no, actually it’s the opposite. You need a background against which the Pop Art manifesto could be written – something more like an anti-world, the fertile ground on which something like Pop Art could actually be invented. Pop Art was clearly a statement against a certain kind of stiffness in society. So I wanted to push this to the extreme and I came up with the idea of using Claes Oldenburg’s I am for an Art (1961) as the text for a conservative, religious, Southern American family saying grace before eating lunch on Sunday. I didn’t expect this scene to turn out funny in the end.

The scene set in the classroom is also very funny.

I think so too. I’m a father myself and some words of the class teacher in that scene actually reflect exactly what I would like to say to my children sometimes. And I think it resonates with us because even though we all know how important good education is, we also have this sceptical anger against so-called ‘good’ education. We hate to say ‘no’ to our children, right? And so there’s this woman in the scene, this teacher who says with utter conviction, quoting Jim Jarmusch, ‘Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination.’ A wonderful breach of taboo. Cate does it so convincingly. And the children are so persuasive as well. If it weren’t so convincing, it would probably not be funny.

In Manifesto you have used a Sol LeWitt text about Conceptual Art for a scene in which Cate Blanchett plays two characters, a news anchor and a reporter, both called ‘Cate’. What is their relationship to LeWitt’s text?

This is an exceptional scene in a way. Rather than performing a manifesto, Cate is inhabited by LeWitt’s writing. She is the manifesto. The tussle between logic and illogic within the text is also inherent in the scene and the characters. It becomes a piece of conceptual art in a way, right?

It does. This scene is very different to the one dedicated to Pop Art that you mentioned earlier. In fact, one of the things that is so compelling about 99 –– Manifesto –– Manifesto is this diversity – every scenario is distinguished by its unique rhythm, pace and aesthetic sensibility.

Yes, I used different recipes for each scene depending on the text. The Manifesto of Futurism for instance, which is very much about speed and acceleration, is placed in the world of high finance: the fast-paced parallel world of the stock exchange where highly efficient computer programmes have let speed become invisible. So in this case the scenario depicts very much a direct translation of the original thought.

You have also used manifestos by artists such as the choreographer and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer, the filmmaker Jim Jarmusch or the architects Bruno Taut and Lebbeus Woods.

The writing in these manifestos is particularly beautiful. As an artist who studied architecture and works with film, I don’t see these disciplines as far away from painting and sculpture, anyway. I especially like the Bruno Taut piece in the collage of architectural manifestos. The architects and filmmakers caused me some trouble, though, because I’d originally wanted there to be a linear and chronological progression through the scenes combining manifestos from various creative disciplines according to the school of thought and epoch in which they were written. But in the end it felt better to keep all the architectural manifestos together, and all the film manifestos together.

That brings us to the question of actuality. In general, are these old manifestos relevant today?

Absolutely. And not just relevant, but also visionary. Art history is a derivation of history and we learn from history. Artists, as well as writers, philosophers and scientists, have always been the ones who have dared to formulate thoughts and visions whose consistency had yet to be proven. The John Reed Club of New York – named after the US-American communist and journalist John Reed – of which many artists and writers were members, published a Draft Manifesto in 1932, in which a scenario of a capitalist world order run out of control is described. It reads as if it were written yesterday. We’re well advised, therefore, to read artist manifestos as seismographs of their age.

Do you have a favourite manifesto?

Many. And now that Cate has interpreted them all, I care for them even more. The manifesto of the American artist and architectural visionary, Lebbeus Woods, of 1993, comes into my mind. It is simply beautiful: pure lyrics, beginning with the sentence, ‘I’m at war with my time’, which echoes the tenor of many manifesto texts I’ve read and used. But Woods’s manifesto ends optimistically with a line full of hope: ‘Tomorrow, we begin together the construction of a city.

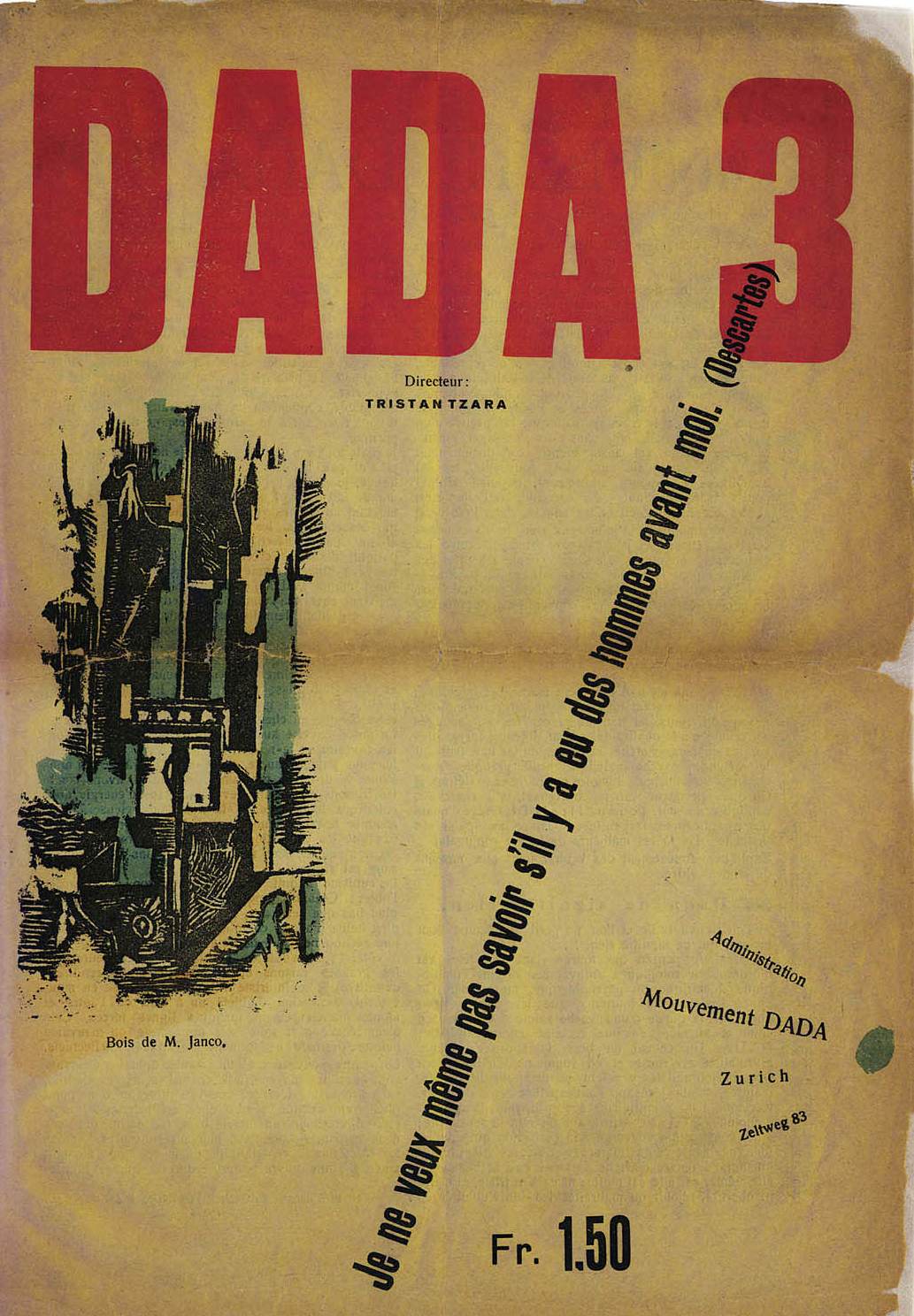

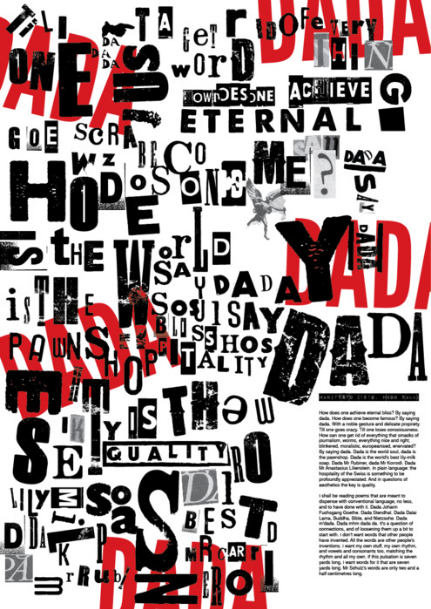

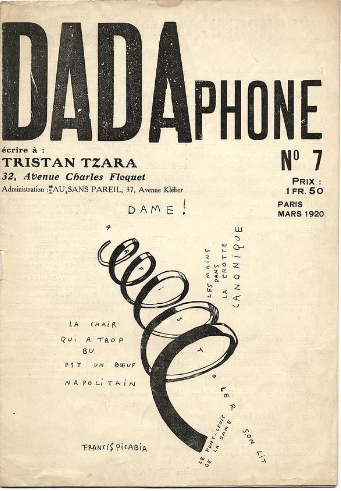

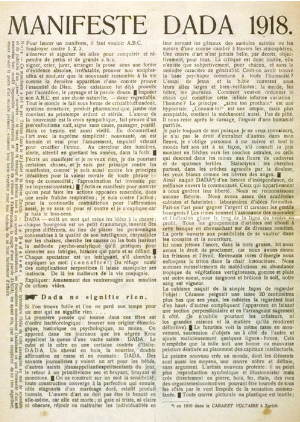

Cover of the magazine directed by Tristan Tzara

Cover of the magazine directed by Tristan Tzara

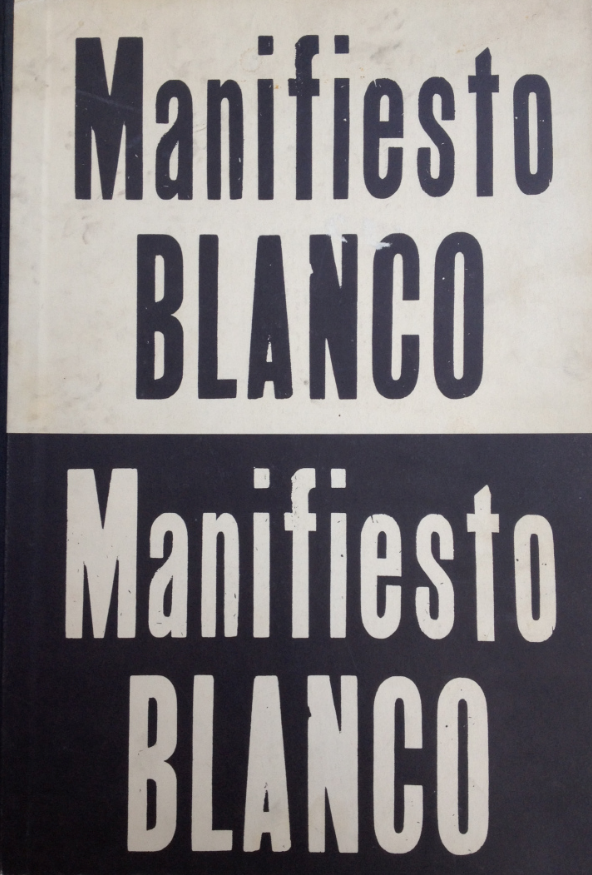

Manifiesto Blanco, Lucio Fontana, 1946

Manifiesto Blanco, Lucio Fontana, 1946

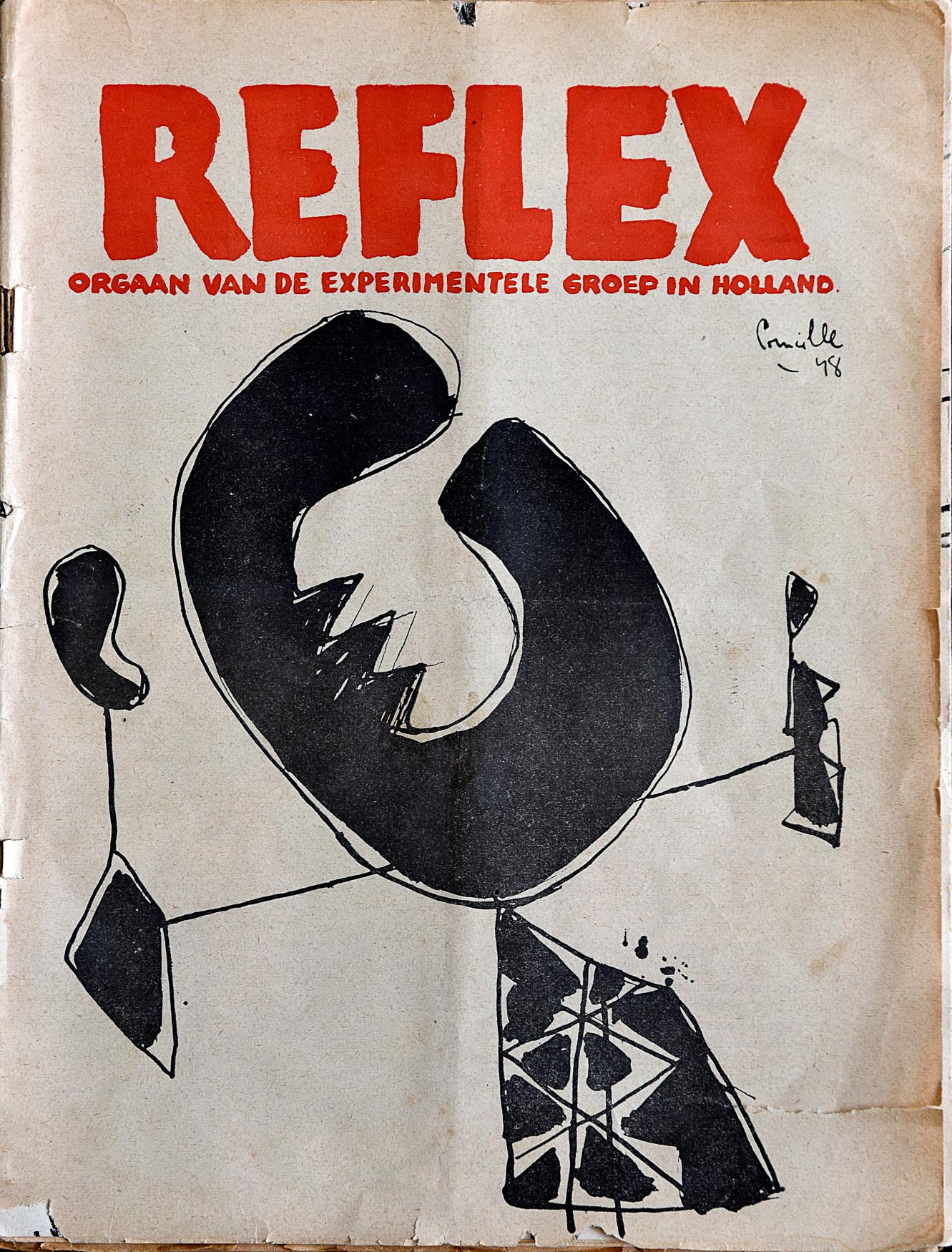

Reflex, 1948. Constant Nieuwenhuys Manifesto

Reflex, 1948. Constant Nieuwenhuys Manifesto

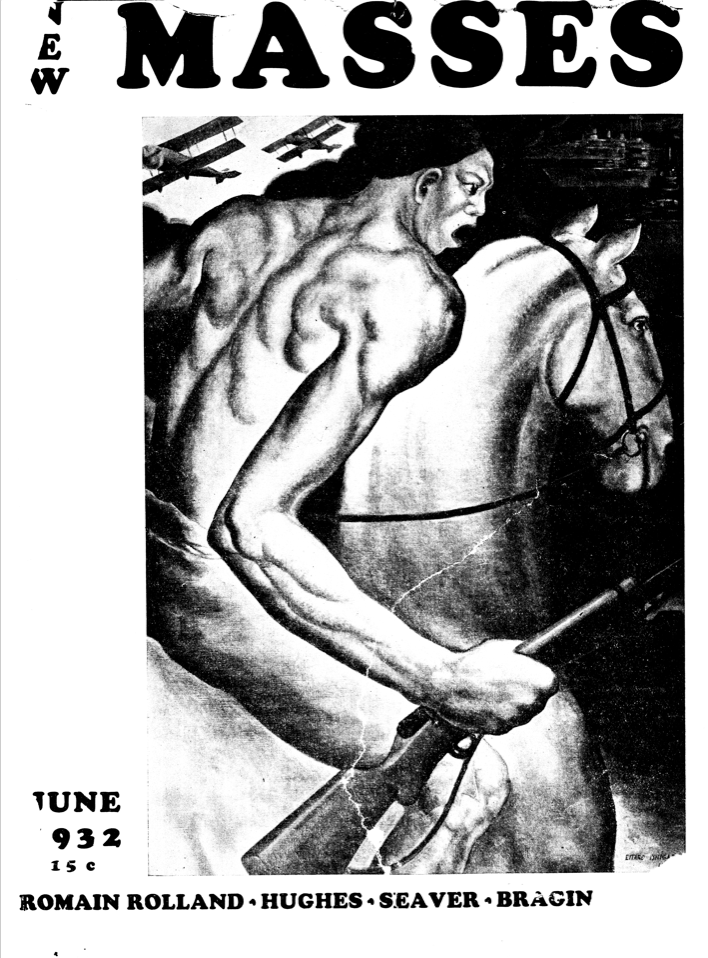

Original image of the Draft Manifesto, John Reed Club, 1932

Original image of the Draft Manifesto, John Reed Club, 1932

To give visible action to words

Anna-Catharina Gebbers and Udo Kittelmann

In: JULIAN ROSEFELDT: MANIFESTO, Koening Books, 2016

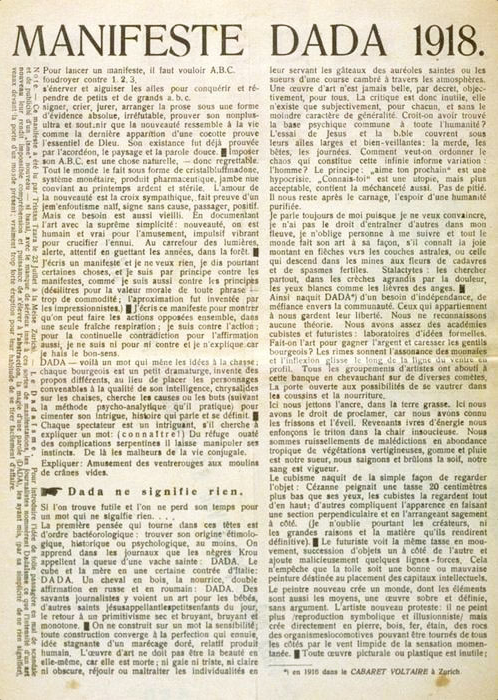

A flickering coloured shape snakes across the black screen, its pulsing light accompanied by a growing hissing noise. For the viewer, it is not immediately obvious what this encroaching object is. It turns out to be a burning fuse that Julian Rosefeldt is using to ignite his film project Manifesto. The aim of a manifesto, after all, is to demolish traditional views with an explosive force. Manifestos call for revolution and herald new eras. Along with the impetus of intentionality and performativity, a mood of departure and subversion is literally ‘inscribed’ within them, as Rosefeldt’s introductory film both reveals and obfuscates. This indeterminacy is deliberate. As the flame of the fuse gradually takes shape, enlarged almost to the point of abstraction, an off-screen voice announces: ‘To put out a manifesto you must want: ABC to fulminate against 1, 2, 3; to fly into a rage and sharpen your wings to conquer and disseminate little abcs and big abcs; to sign, shout, swear; to prove your non plus ultra; to organize prose into a form of absolute and irrefutable evidence.’

With these opening lines from his Dada Manifesto1918, the Romanian-French artist Tristan Tzara (born Samuel Rosenstock, 1896–1963) intentionally evokes associations with the avant-garde manifestos of the Futurists, among others, and plays with the blatant intentionalism of such texts. From this starting point, however, he goes on to develop a Dadaist anti-manifesto that is filled with unsettling ambiguity. His text represents an unspoken but practised antiintentionalism: ‘How can one expect to put order into the chaos that constitutes that infinite and shapeless variation: man?’3 The blurred imagery in Julian Rosefeldt’s introduction is a reference to this critique of modernity and the belief in progress that was so clearly reflected in the Futurist manifestos. Here, as in Tzara’s text, blurring is a purposeful confrontation with the world as we know it. Rosefeldt thus places his filmic blurring in the context of the avant-garde movement.

In Manifesto, Julian Rosefeldt not only examines the concerns and intentions that are so compelling and urgent they must be expressed in the form of a manifesto; he is also interested in the specific rhetoric of manifestos and how they create a ‘call to action’. This leads him to ask: what do we do by saying something? At the action level, a manifesto issues a proclamation and makes a postulation. Over and above this, however, it is intended to shape reality in a very concrete way. The connection between speaking and acting in a manifesto can therefore be analyzed both in terms of content and in relation to speech-act theory.

In a series of lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955, which were published posthumously under the title How to Do Things with Words, the British philosopher John L. Austin (1911–1960) demonstrates that constative utterances also have a performative dimension, and that by issuing an utterance we are doing something – we are performing an illocutionary act.4 In other words: an utterance is invariably an action, and ‘with the aid of linguistic utterances we can perform a wide variety of actions’.5 Julian Rosefeldt explores this theme by developing specific links between his filmed images and the spoken manifesto texts: does a loudly or quietly spoken phrase leave a visible trace on a person’s physical actions? Is embodiment intrinsic to the text? And how do the spoken words alter the perception of the filmed images that are shown concurrently?

The introduction is the only film in this multipart work that does not feature a person on screen. Manifesto clearly wants to show individual characters with their personal struggles, their interactions with others, and their cultural and film historical traditions. And so this first glowing fuse in the darkness is mirrored in a daylight scene: on a misty morning in an industrial park, three elderly women can be seen setting off fireworks like excited young kids. The image has a distant echo of the three children playing with fireworks in Michelangelo Antonioni’s (1912 2007) movie La Notte,6 which captures the ennui of the affluent modern bourgeoisie. In the foreground of Rosefeldt’s film we see a scruffy, bearded man in a grey overcoat, dragging a shopping cart full of collected empty bottles behind him. The film then cuts back to the fireworks exploding in the sky – but now we see them from the bird’s-eye view of a drone. We look down upon the three women and the homeless man, who slowly moves off as the camera flies over the industrial park and a deep female voice is heard off-screen. The speaker is reading excerpts from texts filled with Situationist critique of elitism and capitalism, compiled and collaged by Rosefeldt from manifestos written by Aleksandr Rodchenko (1891–1956), Lucio Fontana (1899–1968), Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920–2005), Guy Debord (1931–1994) and the John Reed Club of New York (1932). In these texts, the artist is hailed as a revolutionary and demands are made to abolish commodities, wage labour, technocracy and hierarchy – life itself is to become art.

In his introductory film, Rosefeldt precedes the quotations from Tzara’s text with a line from The Manifesto of the Communist Party: ‘All that is solid melts into air.’7 This immediately creates a highly ambiguous link between the individual texts, as well as between texts and images, because for Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) it was clear that the bourgeoisie itself could not exist without constantly revolutionizing all relations of society. Conserving the old modes of production in unaltered form had been the condition of existence for earlier industrial classes. Everlasting uncertainty and agitation, on the other hand, was what distinguished the bourgeois epoch.

The Communist Manifesto is in fact the text that is most frequently associated with the term ‘manifesto’. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were commissioned by the Communist League to write this work, which was originally titled Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei [The Manifesto of the Communist Party]8 in the winter of 1847/48. When it was published in early 1848, neither the February Revolution in France nor the March Revolution in the German Confederation had yet taken place. Inspired by the spirit of Enlightenment, the ‘age of revolution’ was a period of social and political upheaval in western societies. Beginning with the America Revolution in 1776 and continuing through the French Revolution of 1789 to the Revolutions of 1848, it was succeeded by the ‘age of capital’ (1848–1875)9: following on from the uprisings against the aristocratic, feudal order, The Communist Manifesto was intended to mobilize the working class to take part in a revolutionary overthrow of capitalism.

By choosing this line as his opening quotation, Julian Rosefeldt also highlights the fact that manifestos are mainly written by young, angry men. Marx had just turned twenty-nine and Engels twenty-seven whe they demonstrated with this approximately thirtypage essay how the written word can fundamentally transform the intellectual and political world. Many of their statements and declamations have become well-known sayings, including the opening line, ‘A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of Communism’, and the call for action with which The Manifesto of the Communist Party concludes: ‘Working Men of All Countries, Unite!’

Following the publication of Marx and Engels’s manifesto in the mid-nineteenth century, the word ‘manifesto’ entered the vocabulary of the labour movement and became a recognized designation for this kind of text. As a generic term, however, it remained firmly rooted in political discourse. Although numerous proclamatory aesthetic texts were also written in the realm of art and literature over the years, the term ‘manifesto’ was rarely used in these contexts until the early twentieth century, when it was adopted by visual artists specifically because of its political implications. After Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944) unleashed a flood of manifesto writing with his Manifesto of Futurism,10 the avant-garde endowed the genre with some distinctive features: the urgent and precise communication of authorial intent; appellative rhetoric; a combative, provocative style; and frequently propagandistic self-promotion.

Julian Rosefeldt recalls the proletarian origins of politicization with his highly ambiguous portrayal of a factory worker – a single mother going through her morning routine of making coffee and preparing breakfast for her sleeping daughter, and then driving to work at a waste incineration plant. It is to be assumed that these important survival rituals do not leave much room for revolutionary activities, yet while she roars through the city on her moped, texts can be heard from ambitious manifestos by architects such as Bruno Taut (1880 1938), Antonio Sant’Elia (1888–1916) and Robert Venturi (b. 1925), or the architectural studio Coop Himmelb(l)au, which was founded in 1968. Taut’s unshakable belief in the power of architecture to completely transform the world, his ‘Wandervogel’ romanticism, and his enthusiasm for the new materials of glass, steel and concrete shatter against this woman’s everyday existence, as she travels from a dreary modernist housing development to a factory where she looks out of a huge glass window onto an alpine landscape of garbage.

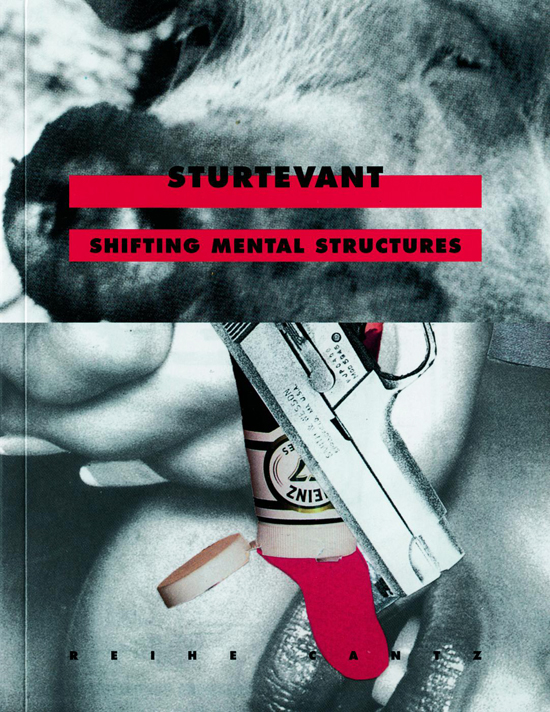

The first avant-garde was on the one hand closely linked to the political utopias of modernism; on the other, it aimed to integrate art into the praxis of everyday life and establish a new, revolutionary aesthetics. An integral part of this was the use of the term ‘avant-garde’, originally a French military expression denoting the ‘advance guard’ that was sent ahead of the massed body of soldiers to enter enemy territory. The new aesthetics was also characterized by its selfstaging in a variety of media, a particular rhetorical style, and the development of specific types of texts such as manifestos. Rosefeldt recalls these aspects by, for example, having an announcer in a television studio read excerpts from manifestos by Sturtevant (1924–2014) and Sol LeWitt (1928–2007) in the typical style of a newsreader. ‘All current art is fake, not because it is copy, appropriation, simulacra, or imitation, but because it lacks the crucial push of power, guts and passion,’12 she declares, quoting Sturtevant in a sharp tone of voice. During the broadcast, Rosefeldt also confronts the rhetoric of the well-groomed newsreader with her alter ego – a field reporter standing in the rain, wearing an all-weather jacket. One is enclosed within the aseptic environment of the TV studio; the other is apparently exposed to the storms of the real world (dramatically simulated using special effects, although the wind and rain machines are ultimately exposed). The field reporter and the studio anchor address each other as ‘Cate’ as they discuss the fact that conceptual art is only good if the idea is good.

Sturtevant, Shifting Mental Structures (1999)

Manifestos are not simply a mode of providing information or giving instructions for action, however. The affirmative nature of their language, their apodictic, imperative style, their declamatory tone, the use of the future tense, hyperbole and superlatives but also the frequent inclusion of lists, memorable sequences and polar thinking are all intended to serve an appellative function. The distinctive style of a manifesto aims to create an emotional impact. Besides texts that are virtually impossible to recite, Rosefeldt has discovered manifestos with truly theatrical qualities. By taking them out of their usual context, he also draws attention to the literary, poetic beauty of numerous art manifestos by the likes of Francis Picabia (1879–1953), Bruno Taut, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes (1884 1974), Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948), Richard Huelsenbeck (1892–1974), AndreÅL Breton (1896–1966), Tristan Tzara or Lebbeus Woods (1940 –2012). To create his text collages, Rosefeldt studies the speech rhythms of the various authors and in doing so reveals surprising parallels between them; the same musical, synesthetic approach is also used to compose his images. He links texts and images both metaphorically – for example, by establishing a connection between the manifestos of the Futurists and stock exchange traders, on account of their shared love of speed – and antithetically, when he puts Claes Oldenburg’s Pop Art manifesto into the mouth of a Southern American housewife. He also invites viewers to experiment by creating their own combinations of images and sounds as they move through the Manifesto installation. With this elaboration of the complex nature of manifestos, Rosefeldt not only gives existing texts a contemporary relevance by placing them in new contexts – a method he has already employed in other works – but for the first time he assigns the leading role to the words themselves.

As a combination of a functional text and an art text,13 the manifesto can be located ‘somewhere between literature and non-literature, poetics and poetry, text and image, word and action’.14 Tristan Tzara’s humorous interventions upset linguistic conventions and hence subvert the logic of language comprehension. The method he recommends for making a Dadaist poem involves dismantling familiar structures and developing new ones, as follows: ‘Take a newspaper. Take some scissors. Choose from this paper an article of the length you want to make your poem. Cut out the article. Next carefully cut out each of the words that makes up this article and put them all in a bag. Shake gently. Next take out each cutting one after the other. Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag. The poem will resemble you. And there you are – an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.’15 Similar approaches based on deÅLcollage were later developed by James Joyce (1882–1941) and Max Frisch (1911–1991), among others; William S. Burroughs (1914–1997) and Brion Gysin (1916– 1986) used what they termed the ‘cut-up technique’. In the new millennium, this practice is also found in the realm of music, where it is known as a ‘mash-up’. It invariably involves subverting expectations in order to move beyond normal practice in the contemporary world.

The thirteen text collages that Julian Rosefeldt has compiled from a large number of art manifestos also subvert expectations, above all through their juxtaposition with his filmed images. Here, there are no angry young men mounting the barricades or declaring their demands to a secret assembly of potential conspirators. On the contrary: the majority of the protagonists are women – often not the youngest – who are either formulating the text as an interior monologue intended only for themselves, or delivering it to an audience that expects anything but a revolutionary call to action.

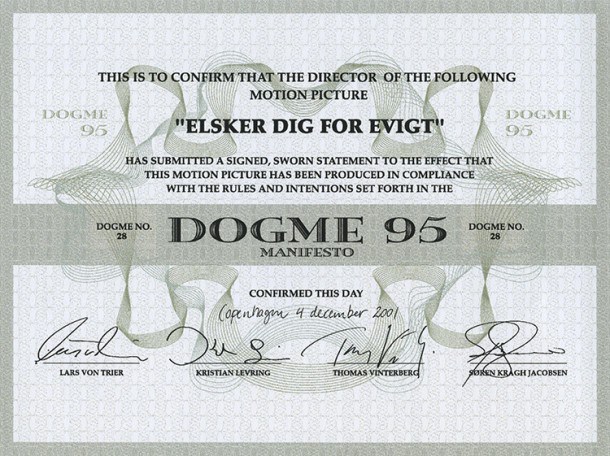

Although the relationship between language and image is not always asyntopical – often a person is visible on screen as we hear their inner voice – the text and the filmed images do not appear to have the same referential objects. The texts do not specify or explain the images, and this serves to emphasize the principle of expenditure, the declamatory style and the expressionistic language that are inherent in manifestos. The effect of this discrepancy between image and language is illustrated by Rosefeldt in a scene where a schoolteacher and her pupils quote passages from manifestos by experimental filmmakers such as Dziga Vertov (1895–1954), Stan Brakhage (1933–2003), Werner Herzog (b. 1942), Jim Jarmusch (b. 1953), Lars von Trier (b. 1956) and Thomas Vinterberg (b. 1969).

Despite the discrepancy between image and text, a connection is made in the viewer’s perception of what is seen. Each of the films shows someone going about their everyday business, doing their job, engaging in their usual activities – basically ‘functioning’ in a normal situation. In the viewer’s mind, due to the intuitive association between sound and images, the monologue becomes the audible testimony of the portrayed character’s inner struggle with their particular situation, or of a conflict they find themselves in. Whether it is an inner voice or an audibly articulated one, what is being ‘discussed’ are alternative possibilities for action, but these actions are never performed. Instead, a decision is made in preparation for an action. In this way, Rosefeldt adds a level of tension that runs counter to the mainly peaceful images, generating the kind of subliminal rumblings which often lead up to the implementation of an action and put viewers on alert.

Rosefeldt uses the appellative nature of the texts to heighten this tension. The verbalizations and subsequent rationalizations that occur in a monologue generally create a certain detachment from a situation, while an interior monologue is only aimed at the person him- or herself. Here, however, although the audience is not present at the fictional level of the respective characters, viewers feel that they are being addressed and challenged due to the proclamatory style of speaking. Rosefeldt draws attention to this aspect by including – at exactly the same point in each film – a moment when the main character looks directly at the viewer and addresses him or her. Different dialects and stylistic elements, such as choice of words and sentence structure, were used to create an individual manner of speaking for each of the protagonists. By turning towards the audience in this moment of synchronicity, however, the characters temporarily put their roles aside, also in a linguistic sense: their individual monologue becomes a monotonous vocalization at a constant, predetermined pitch. As each film has its own set pitch, the combined sounds briefly produce two successive chords16 – diegetically created by the orchestral harmonization of different manifestos.

The stylistic device of the aside does not have the same distancing effect (Verfremdungseffekt) in the Manifesto films as it normally does in the theatre, however. The characters do not use the aside to comment on what is happening in the film, nor do they give us information on the relationship between things or people within the communicative frame of the narrative, nor do they make critical or insulting observations. Nevertheless, the scenic unity is threatened and the fourth wall to the audience becomes porous – the screen becomes a membrane. Strangely enough, however, the characters do not actually step outside their roles; instead, the viewer steps inside the film. The seductive power of the inflammatory texts and the sense of identification with the predominantly female protagonists have an affirmative effect that draws the viewer in.

A further level is added to Manifesto by its leading actor, Cate Blanchett. Her extreme versatility and ability to authentically convey a wide range of speaking styles and dialects enable the viewer to grasp both the variety and the unifying elements of the different manifestos on an emotional level. Over and above this, Blanchett’s international celebrity guarantees that the project will receive media attention far beyond the art audience, and thus emphasizes the work’s manifesto-like character.

As the goals of the avant-garde artists – to break with tradition and move away from the idea that naturalistic representation was art’s primary task, to unify the arts and integrate art into life – also involved communicating sociopolitical ideals, their innovative approaches required careful elaboration and explanation. They wanted art to be not only the expression of, but also the driving force behind, sociopolitical change. The specific correlation between image and text is ultimately what defines the manifesto as a medium of reception control.

Julian Rosefeldt’s complex film installation draws on Guy Debord’s concept of the ‘society of the spectacle’, where relationships and experiences are increasingly mediated by visual images. The ‘crisis of narratives’18 at the end of the twentieth century also contributed to this development. At the same time, however, the growing volume of available images and texts, along with the expansion of the pool of recipients through print media, TV shows, web-based magazines and social media platforms, has led to increasing attempts – by commercial image makers, advertising media, and political bodies as much as by artists – to control reception. The desire to communicate grows, while the individual message gradually loses its distinctive quality and impact due to the endless possibilities for reflection and dissemination. Rosefeldt makes ‘manifest’ how all of this rekindles our desire for manifestos, but also shows how curiously unreal it would seem if we were now to proclaim universal ideals in the form of a manifesto.

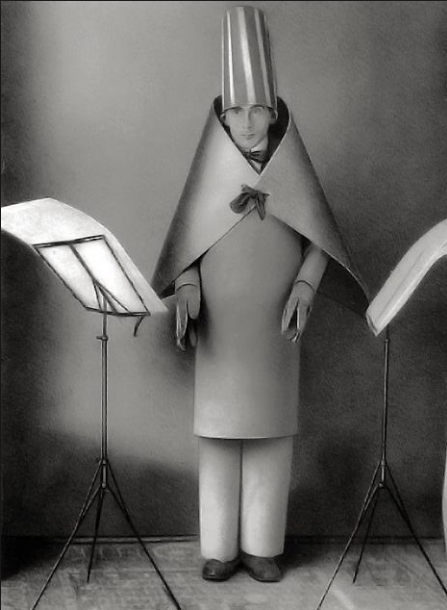

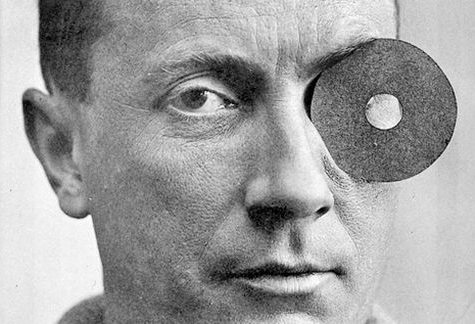

Hugo Ball reciting the poem Karawane, Cabaret Voltaire, 1916

Hugo Ball reciting the poem Karawane, Cabaret Voltaire, 1916

Hugo Ball

Hugo Ball

Dada Manifesto, Hugo Ball

Dada Manifesto, Hugo Ball

Huesos Dada

Paul Auster

Prologue for: Hugo Ball. La huida del tiempo (un diario) con el primer manifiesto dadaísta, Acantilado Ed, 2005. Translation by Roberto Bravo de la Varga

In: http://www.acantilado.es/wp-content/uploads/Huesos_dada_prologo_Paul_Auster.pdf

De todos los movimientos de la primera vanguardia, el dadaísmo es el que sigue teniendo más significación para nosotros. A pesar de su corta vida—comenzó en 1916 con los espectáculos nocturnos del Cabaret Voltaire, en Zúrich, y acabó, de forma efectiva aunque no oficial, en 1922 con las descontroladas manifestaciones en París contra la obra de Tristan Tzara, Le Coeur à gaz—su espíritu aún no ha quedado completamente relegado al olvido en lo remoto de la historia. Incluso ahora, más de cincuenta años después, no pasa un año sin que se publique algún nuevo libro o se presente alguna exposición sobre el dadaísmo, y es más que un interés académico lo que nos mueve a continuar investigando los interrogantes que planteó. Porque los interrogantes del dadaísmo siguen siendo los nuestros y cuando hablamos de la relación del arte con la sociedad, del arte opuesto a la acción y del arte como acción, no podemos evitar recurrir al dadaísmo como fuente y ejemplo. Queremos conocerlo no sólo por sí mismo, sino porque somos conscientes de que nos ayudará a entender nuestro propio presente.

Los diarios de Hugo Ball son un buen punto de partida. Ball, una figura clave en la fundación del dadaísmo, fue además el primer desertor del movimiento, y sus anotaciones sobre el período que va del año 1914 a 1921 son un documento extremadamente valioso. El original de La huida del tiempo se publicó en Alemania en 1927, poco antes de la muerte de Ball, a la edad de cuarenta y un años, a consecuencia de un cáncer de estómago, y está compuesto de pasajes que el autor extrajo de sus diarios editó con una visión retrospectiva clara y polémica. No es tanto un autorretrato como un testimonio de su evolución interior, una rendición de cuentas espiritual e intelectual que va avanzando de asiento en asiento de una manera rigurosamente dialéctica. Aunque hay pocos detalles biográficos, la arriesgada aventura del pensamiento basta para cautivarnos, porque Ball fue un agudo pensador (como partícipe en los inicios del dadaísmo tal vez estemos ante el más fino observador del grupo de Zúrich) y porque el dadaísmo sólo marcó un estadio en su complejo desarrollo, de modo que la visión que obtenemos a través de su mirada nos ofrece una perspectiva que no habíamos tenido hasta entonces.

Hugo Ball fue un hombre de su tiempo y su vida parece encarnar las pasiones y contradicciones de la sociedad europea del primer cuarto de siglo de una forma extraordinaria. Estudioso de la obra de Nietzsche; director de escena y dramaturgo expresionista; periodista de izquierdas; pianista de vaudeville; poeta; novelista; autor de obras sobre Bakunin, la intelectualidad alemana, el cristianismo temprano y los escritos de Hermann Hesse; converso al catolicismo, parecía que, en un momento u otro, había tocado prácticamente todas las preocupaciones políticas y artísticas de la época. Y, sin embargo, a pesar de sus numerosas actividades, las actitudes e intereses de Ball fueron increíblemente coherentes a lo largo de su vida, y al final su carrera entera se puede ver como un intento metódico, incluso febril, de basar su existencia en una verdad fundamental, en una realidad única, absoluta. Demasiado artista para ser filósofo, demasiado filósofo para ser artista, demasiado preocupado por el destino del mundo para pensar únicamente en términos de salvación personal, y con todo, demasiado introvertido para ser un auténtico activista; Ball luchó por encontrar soluciones que de algún modo pudieran dar respuesta tanto a sus necesidades particulares como a las generales, e incluso en la más profunda soledad nunca se vio a sí mismo separado de la sociedad que lo rodeaba. Fue un hombre que tuvo que afrontar grandes dificultades para lograr lo que buscaba, que nunca se fijó una idea de sí mismo y cuya integridad moral le permitió tener gestos decididamente idealistas que no encajaban en absoluto con su delicada naturaleza. No hay más que examinar la famosa fotografía de Ball recitando un poema sonoro en el Cabaret Voltaire para comprenderlo. Está vestido con un disfraz absurdo que lo hace parecer como un cruce entre el Hombre de Hojalata y un obispo enloquecido, y mira fijamente por debajo de un sombrero alto de hechicero con una expresión de incontenible terror en la cara. Es una expresión inolvidable, y esta imagen única de él viene a ser una parábola de su carácter, una perfecta interpretación del interior confrontándose con el exterior, de la oscuridad encontrándose con la oscuridad.

En el prólogo de La huida del tiempo, Ball ofrece al lector una autopsia cultural que marca la pauta de todo lo que sigue: «Éste es el aspecto que presentaban el mundo y la sociedad en 1913: la vida está totalmente encadenada a un entramado que la mantiene cautiva. […] La pregunta última que se repite día y noche es ésta: ¿existe en alguna parte un poder fuerte y, sobre todo, con elvigor suficiente para acabar con esta situación?» En otra parte, en su conferencia de 1917 sobre Kandinsky, expone estas ideas incluso con mayor énfasis: «Una cultura milenaria se desintegra. Ya no hay columnas ni pilares, ni cimientos…, se han venido abajo… El sentido del mundo ha desaparecido.» Estos sentimientos no nos resultan nuevos; confirman nuestra impresión sobre el clima intelectual europeo que se vivía en la época de la Primera Guerra Mundial y se hacen eco de muchas cuestiones que hoy damos por sentadas puesto que han acabado conformando la sensibilidad moderna. Lo que es inesperado, en cualquier caso, es lo que Ball dice un poco más adelante en el prólogo: «Podía dar la impresión de que la filosofía había pasado a manos de los artistas; como si los nuevos impulsos partieran de ellos. Como si ellos fueran los profetas de este renacimiento. Cuando hablábamos de Kandinsky y de Picasso, no hablábamos de pintores, sino de sacerdotes; no hablábamos de artesanos, sino de creadores de nuevos mundos, de nuevos paraísos.» Los sueños de regeneración total no podían coexistir con el más negro pesimismo, y para Ball no había contradicción en esto: ambas actitudes formaban parte de un mismo planteamiento. El arte no era una manera de dar la espalda a los problemas del mundo, era una manera de resolver directamente esos problemas. Durante sus años más difíciles, esta fe sustentó a Ball desde sus primeros trabajos en el teatro—«Únicamente el teatro está en disposición de conformar la nueva sociedad. »—hasta aquel planteamiento suyo, influido por Kandinsky, de servirse de «todos los medios y recursos artísticos reunidos», y más allá, en sus actividades dadaístas en Zúrich.

La seriedad con que estas consideraciones aparecen elaboradas en los diarios contribuye a desterrar algunos mitos sobre los comienzos del dadaísmo, sobre todo la idea de que el dadaísmo era poco más que el desvarío rimbombante e inmaduro de un grupo de jóvenes que rehuían la llamada a filas, una especie de chifladura deliberada al estilo de los hermanos Marx. Hubo, por supuesto, muchas actuaciones del cabaret que fueron sencillamente estúpidas, pero para Ball estas bufonadas representaban un medio para alcanzar un fin, una catarsis necesaria: «El escepticismo consumado también hace posible la libertad consumada. […] Prácticamente se puede decir que cuando desparece la fe, en una cosa o en una cuestión, esta cosa y esta cuestión retornan al caos, se convierten en mercancía no declarable. Aunque, tal vez, el caos alcanzado resueltamente y con todas las fuerzas y, por tanto, la revocación completa de la fe sean necesarios antes de que pueda triunfar una construcción radicalmente nueva sobre los fundamentos de una fe transformada.» Por tanto, para comprender el dadaísmo, al menos en esta primera fase, hemos de verlo como restos de los viejos ideales humanistas, una reafirmación de la dignidad individual en la era de la estandarización mecánica, como una expresión simultánea de esperanza y desesperación. La particular contribución de Ball a las representaciones del Cabaret, sus poemas sonoros, o «poemas sin palabras», confirma esto. Aunque desecha el lenguaje ordinario, no tuvo intención de destruir el lenguaje en sí mismo. En su deseo casi místico de recuperar lo que consideraba un habla primitiva, Ball vio en esta nueva forma de poesía, puramente emotiva, un modo de capturar las esencias mágicas de las palabras. «Con este tipo de poemas sonoros se renunciaba en bloque a la lengua, que el periodismo había corrompido y maltratado. Suponía una retirada a la alquimia más íntima de la palabra…»

Ball se fue de Zúrich sólo siete meses después de la inauguración del Cabaret Voltaire, en parte por agotamiento y en parte por desencanto con la forma en que el dadaísmo estaba evolucionando. Se enfrentó principalmente con Tzara, cuya ambición era convertir el dadaísmo en uno de los muchos movimientos de la vanguardia internacional. Tal como apunta John Elderfield en su introducción al diario de Ball: «Una vez fuera, creyó percibir una cierta “hybris dadaísta” en lo que habían estado haciendo. Había creído que estaban evitando la moral convencional para elevarse como hombres nuevos, que habían dado la bienvenida al irracionalismo como una vía hacia lo “sobrenatural”, que el sensacionalismo era el mejor método para destruir lo académico. Luego empezó a poner en duda todo esto—había llegado a avergonzarse de la confusión y el eclecticismo del cabaret y consideró que aislarse de su época era un camino más seguro y más honesto para alcanzar estas metas personales… » En cualquier caso, algunos meses más tarde, Ball regresó a Zúrich para tomar parte en los eventos de la Galería Dada y para dar su importante conferencia sobre Kandinsky, pero poco tiempo después estaba de nuevo discutiendo con Tzara, y esta vez la ruptura fue definitiva.

En julio de 1917, bajo la dirección de Tzara, el dadaísmo era lanzado oficialmente como movimiento total, con su propia editorial, manifiestos y campaña de promoción. Tzara era un organizador incansable, un verdadero vanguardista al estilo de Marinetti, y al final, con la ayuda de Picabia y Serner, fue apartando el dadaísmo de las ideas originales del Cabaret Voltaire, de lo que Elderfield denomina acertadamente «el primitivo equilibrio de construcción-negación», y acercándolo a la osadía de un anti-arte. Pocos años más tarde, se produjo una nueva escisión en el movimiento y el dadaísmo se dividió en dos facciones: el grupo alemán, liderado por Huelsenbeck, George Grosz y los hermanos Herzefelde, con un enfoque fundamentalmente político, y el grupo de Tzara, que se trasladó a París en 1920 y abogó por el anarquismo estético que a la postre desembocó en el surrealismo.

Si Tzara dio al dadaísmo su identidad, también es cierto que le sustrajo el propósito moral al que había aspirado con Ball. Al convertirlo en doctrina, al aderezarlo con una serie de ideales programáticos, Tzara llevó el dadaísmo a una contradicción consigo mismo y a la impotencia. Lo que para Ball había sido un auténtico clamor que partía del corazón contra todos los sistemas de pensamiento y acción se convirtió en una organización más entre otras muchas. La postura del anti-arte, que abrió el camino a incesantes ataques y provocaciones, era esencialmente una idea inauténtica, porque el arte que se opone al arte no deja por ello de ser arte; no se puede ser y no ser a un tiempo. Tal como Tzara escribió en uno de sus manifiestos: «Los auténticos dadaístas están en contra del dadaísmo.» La imposibilidad de establecer este principio como dogma resulta evidente, y Ball, que tuvo la perspicacia de advertir esta contradicción muy pronto, abandonó en cuanto vio signos de que el dadaísmo estaba convirtiéndose en un movimiento. Para los demás, sin embargo, el dadaísmo se convirtió en una especie de farsa que iba cada vez más lejos. Pero la auténtica motivación había desaparecido, y cuando el dadaísmo finalmente murió no lo hizo tanto por la batalla que había librado como por su propia inercia.

Por otra parte, la posición de Ball no ha perdido hoy la validez que tenía en 1917. Tal como yo lo veo, teniendo en cuenta lo que fueron los distintos períodos y las tendencias divergentes dentro del dadaísmo, el momento en que participó Ball sigue siendo el de mayor fuerza, el período que nos habla hoy con mayor poder de convicción. Tal vez sea una visión herética, pero cuando consideramos cómo se agotó el dadaísmo bajo la influencia de Tzara, cómo sucumbió al decadente sistema de intercambio en el mundo del arte burgués, provocando al mismo público cuyo favor estaba solicitando, parece que esta rama del dadaísmo debe verse como un síntoma de la debilidad esencial del arte bajo el capitalismo moderno, encerrado en la jaula invisible de lo que Marcuse ha llamado «tolerancia represiva». Sin embargo, como Ball nunca trató el dadaísmo como un fin en sí, conservó su flexibilidad y fue capaz de usarlo como un instrumento para alcanzar metas más altas, para producir una crítica genuina de su época. Dadaísmo, para Ball, era simplemente el nombre de una especie de duda radical, una manera de dejar a un lado todas las ideologías existentes y avanzar en el análisis del mundo circundante. Como tal, la energía del dadaísmo no puede agotarse jamás: es una idea cuyo momento siempre es la actualidad.

El retorno final de Ball al catolicismo de su infancia, en 1921, no es en realidad tan extraño como podría parecer. No representa un verdadero cambio en su pensamiento y en muchos sentidos puede considerarse sencillamente un paso más en su evolución. Si hubiera vivido más tiempo, no hay razón para pensar que no habría experimentado nuevas metamorfosis. De hecho, en sus diarios descubrimos una continua superposición de ideas e inquietudes, de modo que incluso durante el período dadaísta, por ejemplo, hay repetidas referencias al cristianismo («No sé si, a pesar de todos nuestros esfuerzos, iremos más allá de Wilde y Baudelaire; si, a pesar de todo, no seguimos siendo simplemente románticos. Seguro que hay otros caminos para que se obre el milagro, también otros caminos para oponerse…: la ascética, por ejemplo, la Iglesia.») y durante la etapa de su catolicismo más serio hay una preocupación por el lenguaje místico que recuerda claramente a las teorías sobre los poemas sonoros de su período dadaísta. Como señala en uno de sus últimos apuntes, en 1921: «El socialista, el esteta, el monje: los tres están de acuerdo en que la moderna cultura burguesa es responsable de la decadencia. El nuevo ideal tomará sus nuevos elementos de ellos tres.» La corta vida de Ball fue una lucha constante por lograr una síntesis de estos distintos puntos de vista. Si hoy lo consideramos una figura importante no es porque lograra descubrir una solución, sino porque fue capaz de plantear los problemas con semejante claridad. Por su coraje intelectual, por la convicción con que se enfrentó al mundo, Hugo Ball sobresale como uno de los espíritus ejemplares de nuestro tiempo.

Paul Auster, 1975

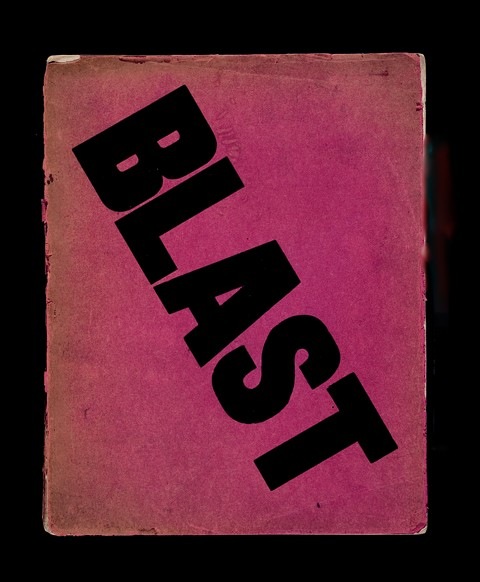

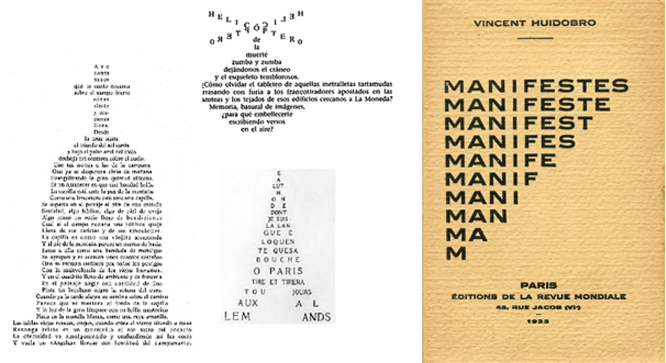

Wyndham Lewis, Manifesto en BLAST, 1914

Wyndham Lewis, Manifesto en BLAST, 1914

Manifiesto Estridentista, 1921

Manifiesto Estridentista, 1921

Lars von Trier / Thomas Vinterberg, Dogma 95 (1995)

Lars von Trier / Thomas Vinterberg, Dogma 95 (1995)

Manifiestos argentinos. Políticas de lo visual 1900-2000

Rafael Cippolini

En: Rafael Cippolini. Manifiestos argentinos.Políticas de lo visual 1900-2000, Adriana Hidalgo Editora, 2003

Fuente: http://www.fba.unlp.edu.ar/visuales3/material/2012_cippolini.pdf

Políticas del canon: manifiesto y legitimación

El canon es un sistema de jerarquías impulsado, históricamente, mediante diversos mecanismos de legitimación cuya forma y articulación se renueva y redefine continuamente.

Los manifiestos sostienen y socavan, admiten y destruyen la posibilidad de un canon. La noción de canon es compleja, ya que necesita e implica un conjunto de relaciones simbólicas que se extiende en la creación de su propia topología: conocemos distintos cánones, no solo temáticos (adscriptos a un orden epistemológico estricto) sino geográficos en tanto nacionales. Así distinguimos cánones locales frente a un Canon Universal que a su vez los contiene. Su otra realidad es temporal: el Canon propone ininterrumpidamente criterios de valoraci6n distintos y consagraciones diversas. Estas variaciones bien pueden denominarse «políticas del Canon".

La presencia de la mutable forma del manifiesto es uno de los principales agentes en las dinámicas de este proceso. Las estrategias de legitimación poseen efectos retroactivos: la valoración cambia su signo y los "logros" de un período histórico se revisan en otro.

De manera que, frente a la voz fuerte de un Canon se alza la voz estratégica, siempre menor e incisiva del manifiesto.

EI erudito alemán Ernst Curtius demostró lo veloz que puede resultar, en la conformación del mismo Canon, el sistema que logra que artistas y obras asciendan y desciendan mediante un remolino de fuerzas que muchas veces toma la forma de un sistema de premios y castigos.

Tal labilidad del Canon no se explica sino par su puro desplazamiento. En realidad debería entenderse como una suma de capas geológicas (más que genealógicas). De estas diferencias de identidad se aprovecha el manifiesto para provocar un orden que, si bien no siempre es nuevo, al menos, es disímil del reinante.

En el caso de las artes visuales, el Canon es una narración que se modifica, a la que se le sobreimprimen voces continuamente, formando un palimpsesto que actúa imperativamente sobre la apreciación de las imágenes que un país, región o grupo produce. EI papel del manifiesto en este relato resulta crucial.

Por lo general el sujeto del enunciado necesariamente no se corresponde con los artistas favorecidos por el Canon. Habitualmente, la buena suerte de las tentativas de la voz disidente con respecto de las operatorias de la consagración o sus beneficiarios, corresponde a aquellos que poseen un discurso textual, argumental y estilísticamente sugestivo y, en tanto, más persuasivo, mas eficaz. La eficacia se constata en sus efectos siempre múltiples.

(...)

EI manifiesto y la puesta en escena de un sujeto

La función más invariable que presenta un manifiesto es generar, inventar, poner sobre la escena un sujeto. Este sujeto es muchas veces plural y será el titular de un mecanismo (él mismo como procedimiento, una vía) de apropiación.

Un sujeto que se apropia de discursos, que utiliza la forma de saberes y aseveraciones que le son ajenas. A lo largo del siglo XX, este sujeto se presentó en múltiples aspectos y apropiándose no sólo de los enunciados propuestos en los discursos del arte, sino de la cultura universal en general.

Los manifiestos artísticos, escritos por plásticos, por artistas de la imagen, saquearon de todas las canteras: de las ciencias, de la religión, de la política, de las otras artes (muchos manifiestos presentan claros efectos dramáticos o literarios).

Uno de los primeros manifiestos argentinos sin dudas es "EI dibujo en la escuela primaria. Pedagogía. Metodología" ", publicado en 1911, y cuyo autor es eI pintor Martín Malharro. Presenta rodos los síntomas de una apropiación. Malharro se apodera de sus propios recursos: él mismo es maestro, profesor de dibujo y pintura, inspector técnico de dibujo, director de cursos temporarios de dibujo en el Ministerio de Instrucción Pública.

A su vez, utiliza todo su repertorio para intervenir ahí donde desea: la Academia, órgano que legitimaba la labor de un artista. Malharro no sólo usa la articulación de su discurso pedagógico proponiendo un nuevo método de enseñanza, sino ataca frontalmente y sabotea minucioso el mecanismo institucional que aprueba y califica el trabajo artístico.

Escritura de artista y expresiones extratextuales

Como afirma el pintor y curador Jorge Gumier Maier a propósito de la pintura, conviene parafrasearlo ahora y anotar que el manifiesto es algo que se debe sostener en cada escena, en cada aparición . Un manifiesto es una intervención, y en cuanto tal sus efectos siempre resultan focalizados y concebidos para provocar una situación determinada.

Para conseguir esa focalización presenta una escritura. El manifiesto, tal como lo concebimos, es escritura de artista. Muchas veces se denominó "manifiesto" a diferentes expresiones extratextuales. Un ejemplo sería el afiche utilizado por el grupo Ar Detroy" en 1991, titulado "Eco de silencio en el mundo", donde todo lo sostiene la imagen y no aparece palabra alguna.

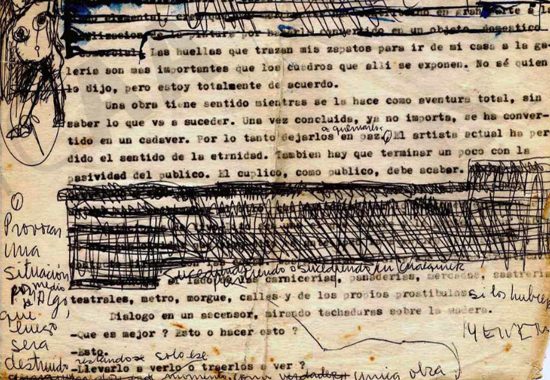

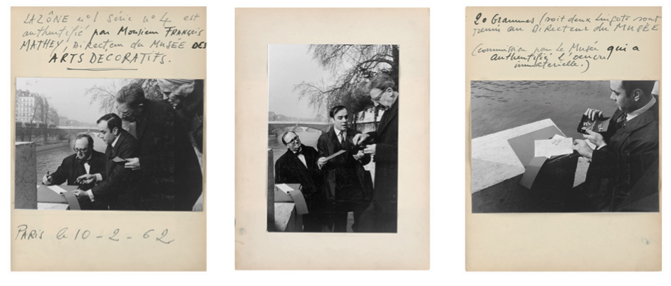

Otro ejemplo, más complejo, es "el gran manifiesto -rollo arte vivo- dito" ", fechado en Ávila en 1963, obra del pintor Alberto Greco, en el cual se mixturan, en unívoca narración, dibujos en tinta, collages y textos manuscritos deliberadamente fragmentarios y autorreferenciales. En este caso, la escritura de Greco se potencia con las imágenes que la acompañan. De rodas maneras, este es un caso bastante atípico.

Alberto Greco, “Manifiesto Vivo-Dito del Arte-Vivo,” 1962

EI manifiesto, entonces, es una forma de escribir y de hacer pública esa escritura, de presentación de un artista visual en tanto escritor (por supuesto, en muchas ocasiones también como diseñador, diagramador y tipógrafo). EI manifiesto, además de hacer pública una escritura, prepara la puesta en escena para esa escritura.

La escritura, como herramienta, tiene aquí la finalidad de provocar.

Provocar al discurso del arte vigente, a las formas presentes de promoción y legitimación. Ahora bien ¿quién genera ese discurso del arte? ¿'Cuáles son las fuentes de esa producción? ¿Cómo, con qué, desde dónde se construye? ¿Las escuelas? ¿Los críticos? ¿Otros artistas, establecidos, más reconocidos?

Los manifiestos centran su objeto en la construcción del enemigo: en los profesores, en los críticos en tanto creadores y difusores de ese discurso que se pretende intervenir, en el gusto de la sociedad en su conjunto (es muy común que un manifiesto ataque la conformidad de un gusto establecido para generar un descontento que obligue a reformular las leyes de aceptación de una estética determinada).

Para lograr su fin el artista se convierte en crítico, es decir, utiliza la palabra, la escritura, para desestabilizar una pretensión; o bien cede la palabra a un crítico que se convierte así, momentáneamente en un artista. A veces el manifiesto es un silencio: es la sustracción, el robo del enunciado. La ambigüedad de la sentencia en (la pipa de) Magritte podría funcionar en este sentido.

Es imposible divorciar la escritura de la historia, ya que ésta (la escritura) se vuelve histórica en cada lectura. EI manifiesto tiene como objetivo un reconocimiento particular. Ninguno tiene pretensión de eternidad.

Más que sentar una posición, el manifiesto busca sentar una oposición.

Muchas veces se trata de generar un escándalo. Otras, de la emergencia de un dogma. La primera, de acelerar el caos. La segunda, de instaurar un orden: presuponer una creencia.

EI manifiesto como herramienta de exploración de la realidad

Muchas veces la emergencia de un dogma es en sí un escándalo; en medio de una situación, de un contexto caótico, el orden que intenta implementarse tendrá a futuro efectos insospechados, convocará nuevos caos. Podríamos entender como caos, en estas oportunidades, a los mecanismos de enunciado que, una vez librados a su funcionamiento, provocan los resultados mas insólitos, tanto en sus relaciones textuales como extratextuales, políticas. La escritura de la historia, muchas veces, podría definirse como un ejercicio descriptivo, basado en la narración de estas instancias. Se aplica una medida, es decir, una creencia peculiar, instrumentándola en la eficacia propia del discurso.

Una medida, lo que debe entenderse como unidad comparativa, patrón; de ella nacerá, un juego de relaciones, una referencia desde la cual tratar de entender un proceso, algunos acontecimientos.

Un manifiesto actúa sobre lo real a la vez que se convierte en una herramienta de exploración analítica de esa misma realidad. No en otro sentido jamás abandonará su naturaleza política, transformadora. Cada manifiesto resguarda un núcleo secreto de intenciones que constituyen el corazón de su capital simbólico. De ese cúmulo, de esos pequeños sistemas que llamamos capitales simbólicos, resulta imperioso trazar, provisoriamente, un boceto de arqueología.

(...)

EI manifiesto artístico como instrumento político

Lo clásico consiste en fijar la noción de manifiesto artístico como un préstamo, una transformación derivada o mera variable formal de la figura del manifiesto como instrumento político.

De esta manera se supedita la acción del arte, su campo mismo y hasta su razón de ser a la posibilidad y preeminencia de una realidad social, es decir: eI arte entendido como actividad que encuentra su especificidad en un contexto colectivo y de interpelación.

Se justifica así la necesidad política de las vanguardias: la etimología de origen y su proyecto de renovación de la vida humana como síntoma.

En cuanto a su constitución, la sumatoria de elementos parecería confirmarlo: una primera persona plural, la voluntad de ganar aliados para una causa, su exhaustividad persuasiva, el cuestionamiento de un estatuto tomado como regulador de causas y efectos.

Este esquema tradicional y político en su sentido más lato, deja consignada de una vez y para siempre la inevitabilidad de una causa determinante. Ésta será eternamente la misma, la transformación social, la diatriba del artista en el cuestionamiento de diversos factores de malestar colectivo. Esta causa excedería el ámbito de praxis del artista o bien entendería a este mismo ámbito como la atención dirigida en unívoca dirección: en las peculiaridades de la vida de relación.

El manifiesto artístico, según esta creencia, carecerla de lábiles márgenes de ductilidad formal y se ajustaría, en permanencia histórica, a un mismo prototipo ajustado y desajustado por levísimas variantes de una política vinculada a determinaciones estatales.

Desde los tramados de lectura de este libro, una de las intenciones es proponer un estado de cuestión diverso y nuevas especulaciones en torno a la determinación de una causa única y definitiva, instalada estructuralmente casi como imposición de una verdad indiscutible y mistificante.

Por el contrario, vaciando de antemano y cuestionando esta causa única, insistiendo en la naturaleza del manifiesto de artista como obra, el repertorio exhibido puede leerse en un horizonte muchísimo menos acotado, menos imperativo, participante del espíritu lúdico, libre, irresponsable, nunca esclavo de los caprichos de la grey, de la arenga de creer conocer de antemano todas las necesidades de una colectividad.

Por mera contraposición, la emergencia de diversas variables en la formalidad de los manifiestos sugiere la hipótesis de que éstos, como producción textual, intentan descubrir diferentes jerarquías atenidas siempre a diversos órdenes de necesidad.

Siendo as! posible descubrir, incluso inventar, nuevas necesidades, la idea de hombre, la definición de éste como sujeto, se libera de la sumisión de ser mero factor de obediencia a un repertorio anterior. Dado que el hombre, como tal, puede redefinir su condición en amplitudes casi inimaginables, sus instrumentos de expresión pueden mutar y reinventarse continuamente.

Como se lee, el atomizar la posibilidad única en la causa del manifiesto artístico, constituye todo lo contrario a su despolitización. Muy por el contrario, bien debe entenderse como una nueva politización, como la radicalidad de su objeto. Como la negativa a aceptar la tesis por la cual el arte en tanto actividad, en cuanto productor de realidad, no es otra cosa que un epifenómeno de lo político a secas.

El arte genera sus propias políticas en tanto indaga la novedad de otras necesidades. El arte no necesariamente es un producto social, sino que, no sólo posee un objeto autónomo inspirado en la libertad esencial del individuo, en sus sueños, pensamientos, percepciones y emociones no legisladas de antemano por orden alguno, sino que también en muchas oportunidades ha sido el mismo arte el que se adelantó, en su red de visiones y procesos, a síntomas que disciplinas como la sociología, la antropología, incluso la filosofía y la historia leyeron en absoluto destiempo.

He ahí su capacidad de vanguardia.

Marinetti hablando sobre el poeta-soldado en el Teatro Politeama de Buenos Aires

La idea de una vanguardia artística de status independiente es propia del siglo XX. Su promotor fue el poeta italiano Filippo Tommaso Marinetti quien, el 20 de febrero de 1909, publica en Le Figaro de Paris, un texto titulado "Fundación y manifiestos del futurismo".

EI manifiesto propiamente dicho consta de once ítems, de una introducción en clave narrativa y de una conclusión conceptual de base programática.

Este texto, de inmensa repercusión, señala una diferencia sustancial: es el arte el que genera y propone un disturbio social y político cuyas metas coinciden con un violento cambio de percepción. Su obertura se escenifica como la puesta en relato de un mito de origen: el poeta y líder, junto a sus amigos, habiendo "pisoteado largamente sobre opulentas" alfombras orientales" "discutiendo ante las fronteras extremas de la lógica y habiendo "ennegrecido mucho papel en escrituras frenéticas" "cubierto el rostro del buen fango de los talleres -empaste de escorias metálicas, de sudores inútiles, de hollines celestes" "contusos y con los brazos vendados" dictaron la Primera Voluntad a todos los hombres "vivos" de la tierra.

Su estilo es vigoroso y épico:

(..) ¡Vamos amigos! Finalmente, la mitología y el ideal místico han sido superados. ¡Estamos a punto de asistir al nacimiento del Centauro y pronto veremos volar los primeros Ángeles!. ... iHabrá que sacudir las puertas de la vida para probar sus goznes y cerrojos!' .. iPartamos! iHe aquí, sobre la tierra, la primerísima aurora! iNo hay nada que iguale el esplendor de la roja espada del sol, que brilla por primera vez en nuestras tinieblas milenarias!

Entre sus premisas se han inmortalizado:

1. Nosotros queremos cantar el amor al peligro, el hábito de la energía y de la temeridad. (..)

4. Nosotros afirmamos que la magnificencia del mundo se ha enriquecido con una belleza nueva: la belleza de la velocidad. Un automóvil de carrera con su capó adornado de gruesos tubos parecidos a serpientes de aliento explosivo ... un automóvil rugiente que parece correr sobre la metralla, es más bello que la Victoria de Samotracia. (..)

9. Nosotros queremos glorificar la guerra -única higiene del mundo-, el militarismo, el patriotismo, el gesto destructor de los libertarios, las hermosas ideas por las cuales se muere y el desprecio por la mujer. (. . .)

10. Nosotros queremos destruir los museos, las bibliotecas, las academias de todo tipo, y combatir contra el moralismo, el feminismo y toda cobardía oportunista o utilitaria.

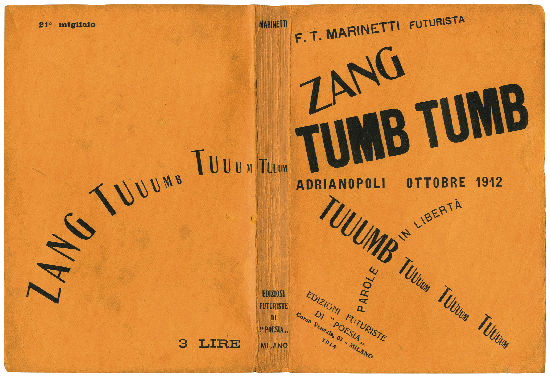

Tapa de Zang Tumb Tumb; Adrianopoli Ottobre 1912; Parole in Libertá (1914)

Hay quienes sostienen que la noción de vanguardia en las artes es anterior a dicho texto. Tal confusión existe porque más de un siglo antes la política utilizó el término, tornado de la jerga militar, para designar a quienes, dentro de la conformación de las fuerzas armadas, se adelantan para la exploración y la ofensiva. Así, algunos de los denominados por Marx socialistas utópicos, formularon que, a una "comunidad de vanguardia", corresponde un "arte de vanguardia".

En tales casos, la existencia del arte es subsidiaria y dependiente de una "política de vanguardia" previa, de un proyecto social que lo antecede.

La novedad de Marinetti es que desde el arte desea cambiar tanto el presente como las formas valorativas retrospectivas.

Tanto el cubismo como el fauvismo no fueron vanguardias sino escuelas. En primer término, la influencia de éstas se circunscribió, mayormente, al campo de las artes visuales, a diferencia del futurismo cuya pretensión fue modificar y crear, desde sus principios, multitud de disciplinas, de la música a la gastronomía. Fauvismo y cubismo fueron escuelas heterodoxas, en las cuales la idea de pedagogía, de transmisión de saber, era sobredeterminante.

La discusión es vasta. Juan Pablo Renzi publicó, en la revista Espacios, de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Buenos Aires, n 4/5 de noviembre-diciembre de 1986, un texto titulado "Cien años de vanguardias" en el cual afirmaba:

Acordemos, desde ya, que la era moderna en pintura se inaugura con el escándalo que produjo Le dejeneur sur I'herbe de Manet en el Salón de los Rechazados de París en 1863 y que la muestra de los impresionistas en el estudio del fotógrafo Nadar, en abril de 1864, también en Paris, puso en circulación su primer movimiento de vanguardia.

Más de cien años en los que, con estupor e indignación, un público cada vez mayor ha celebrado o vilipendiado la aparición de más de treinta movimientos artísticos de vanguardia. Haciendo un promedio, podríamos decir que durante un siglo, cada tres años y fracción ha habido una nueva propuesta estética para el arte de Occidente. Dando apenas el tiempo necesario para respirar y opinar, el movimiento moderno se convierte en el proceso más rico y contradictorio de la historia de las artes visuales.

Renzi alude a una concepción amplia, la misma que utiliza, por ejemplo, Cyril Connolly en sus reflexiones y catálogos sobre el Movimiento Moderno.

EI Movimiento Moderno comenzó como una revuelta contra los burgueses en Francia, los victorianos en lnglaterra y los materialismos de Estados Unidos. EI espíritu moderno fue una mezcla de ciertas cualidades intelectuales heredadas de la llustración: lucidez, ironía, escepticismo, curiosidad intelectual, combinada con la intensidad apasionada y la sensibilidad exaltada de los románticos, su rebelión y sentido de la experimentación técnica, su conciencia de que vivían en una época trágica.

Se ha dicho que una de las funciones del manifiesto consiste en poner en escena un sujeto. Este sujeto, sin lugar a dudas, cumple un rol histórico como productor de enunciados. La singularidad del mismo es fundante al momento de proporcionar una lectura disímil, porque aporta otros elementos en el proceso de interpretación de la historia de las artes.

El caso de Marinetti, entonces, resulta paradigmático.

(...)

Ideologías, mercancía y mercado del arte

Uno de los grandes inventos del capitalismo es que todo lo existente, legal o ilegalmente, puede ser caracterizado como mercancía. EI siglo XX amplió los límites conocidos de este término hasta posibilidades antes inimaginables o apenas esbozadas. Así, las ideologías tuvieron, a lo largo de cien años, su valor diferencial de mercado, lo mismo que las estrategias políticas. Todo, según la óptica en cuestión, tiene un mayor o menor rédito. Las llamadas escrituras de artista de las que los manifiestos, en tanto forma, no son más que un ejemplo, no dejan de atenerse a esta lógica de evaluación.

EI mercado de arte define el juego de ofertas y demandas que las galerías de arte y casas de subastas ponen en circulación, determinando y adaptándose al consumo de coleccionistas, amantes o especuladores del arte. Pero también, y soterradamente, la palabra adquirió otros sentidos, establecidos ya no en una economía librada al flujo de capital monetario sino también simbólico.

Y si bien esta economía simbólica puede medirse en términos dinerarios, asimismo posee una independencia eidética que le proporciona disponibilidad plena en el dominio teórico.

No siempre las obras mas significativas de una época, aquellas en que pueden captarse los rasgos plenos de un período determinado y que, por lo mismo, en muchas oportunidades hacen las veces de puesta en abismo del lapso en cuestión, son las más favorecidas en la evaluación monetaria. En innumerables ocasiones éstas resultan ajenas a la promoción de los catálogos y las muestras respectivas.

No siempre los artífices de las vanguardias de las primeras décadas del siglo intentaron sustraerse de la ventaja económica que podía inclinarse en su beneficio.

En septiembre de 1918, Marcel Duchamp llego a Buenos Aires desde Nueva York, habiendo previamente realizado una breve escala en Barbados". Viajó acompañado de Ivonne Crotti (su hermana Suzanne estaba casada con Jean Crotti) y se hospedó en el Hotel Plaza. Partiría recién en junio del siguiente año.

Si bien en los meses que residió en el país se sabe que jugó al ajedrez y proyectó tres obras, un celebre ready-made titulado Intrucciones para el Readymade malhereux, un estudio para la esquina derecha inferior del Gran Vidrio (A regarder d 'un oeil) y Stereoscopie a la main, fue menos difundido que su fallido objetivo había sido intentar realizar una exhibición de una treintena de obras cubistas en una galería comercial, con la esperanza de iniciar así un posible tráfico. A sus planes se sumaba la intención de importar bibliografía ilustrativa, ejemplares de obras de Apollinaire y Metzinger que actuarían como difusoras de una tendencia sobre la que casi todo se ignoraba en el medio. EI proyecto, cuyo nombre pudo haber sido Cubify B. A. ("Cubificar Buenos Aires") resultó un rotundo fracaso.

El único ready-made que Duchamp ideó en Buenos Aires fue un regalo que envió por correo a su hermana Suzanne con motivo de su boda con Jean Crotti

Cincuenta años más tarde, el discurso más visible demarcatorio de aquello que el mercado resulta para el mundo del arte seguía centrándose en una consideración peyorativa. Mientras que Romero Brest afirmaba solitariamente que era necesario un cambia drástico y puso en funcionamiento, tras el cierre del Insrituto Di Tella, una empresa dedicada al diseño, productora de objetos de uso y elementos de decoración, que se llamó "Fuera de Caja. Centro de Arte para Consumir", cuyo local funcionó en la galería del Hotel Alvear, Aldo Pellegrini escribía un manifiesto acompañando una exhibici6n de Libero Badii. Horacio Coll, Ennio lommi, Alberto Heredia y Aldo Paparella, inaugurada el 11 de junio de 1971 en la galería Carmen Waugh, cuyo título fue "El artista y el mundo del consumo":