Curatorial Text

by Marco Scotini

—

Synopsis of the Works

Gender Disobedience

Radical Ecologies

Insurgent Communities

Diaspora Activism

—

THE DISOBEDIENCE ARCHIVE

Interview with curator Marco Scotini during the Istanbul Biennial

—

The Disobedience Archive at the Venice Biennale

by Elvira Vannini

—

Power and Disobedience

by Mike Watson

—

The Disobedience Archive

by Martina Angelotti

Text by the curator Marco Scotini

Disobedience Archive is a multiphase, mobile, and evolving video archive that concentrates on the relationship between artistic practices and political action. Developed by the curator and art theorist Marco Scotini in 2005, the project generates an atlas of contemporary resistance tactics from direct action to counterinformation, from constituent practices to bioresistance. It also functions as a “user’s guide” to social disobedience, encompassing hundreds of documentary elements spanning decades.

Disobedience Archive investigates art activism that emerged after the end of modernism and comprises hundreds of video and film images that reveal the mediatised nature of history. On the one hand, it aims to show precisely what corporate media, as the central agents of political authoritarianism, attempts to conceal or remove from sight. On the other, it aims to take back control of the violent expropriation of experience and, in turn, ends up producing history and rendering it visible. Presented twenty times in different countries, Disobedience Archive transforms each time without ever assuming a final configuration. Whether in the form of a parliament, a school, or a community garden, the project turns the archive, typically static and taxonomic, into a dynamic and generative device.

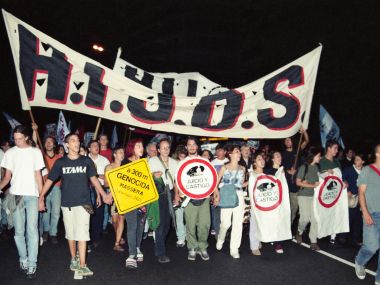

For PROA21, Disobedience Archive embodies the topic of the street (la calle) as one of the privileged symbolic spaces of collective subjectivity and new social protagonisms. On this occasion it presents four sections including 36 films: Diaspora Activism deals with transnational migration processes in the context of hegemonic neoliberalism, as a struggle that drives new ways of inhabiting the world and questions the very meaning of citizenship. Gender Disobedience is, in continuity with the previous section, dedicated to nomadic subjectivities, conceived as a rupture of heterosexual binarism. This section brings together the alliances between activism that critiques capitalism and the LGBTQ+ movements that have emerged globally. Radical Ecologies builds frontlines of solidarity in the fight against assaults on human and more-than-human worlds and projects a vision of a more caring future. Insurgent Communities finally addresses the fight for freedom in places where wars, state oppression, and the aftermath of colonisation limit the scope and possibilities available to human life and other life forms.

Gender Disobedience

Maria Galindo y Mujeres Creando

Revolución puta, 2023

51’40’’

Revolution Puta is both a cinematic political manifesto and a poetic visual story. The film is the result of twenty years of “fight with prostitutes and with different groups for self-managed sexual work, without masters or pimps”. The social influence runs through the entire reflection and permeates the aesthetic proposal: poor women speak starting from their class consciousness, without embellishing or sanitizing poverty. The film is in fact the place of the “first-person word” through a direct interpellation of the members of the organizations OMESPRO La Paz and OMESPRO Santa Cruz as protagonists and narrators of the story (Organización de Mujeres en situación de prostitución). The cinematic language adopted by Galindo is heterodox, difficult to classify and unacceptable for a Europeanizing and colonized cinematic taste, also thanks to the non-conformist and anarchic attitude reflected in her work. The film is structured into four thematic short films: The knowledge of the whore, The whore and the work, The whore and the State and Testament. Although they are woven into a feature film, each maintains its own independent structure. In these times of mutation in which images belong simultaneously to different linguistic spaces, Revolution Puta was not produced for “film festivals”, but for social imaginaries. It can be projected in rooms, but also in improvised places, in classrooms, in debates. It has the vocation and versatility to invade all types of spaces except the internet because on the latter the video would be immediately censored by a reactionary and patriarchal culture.

Ege Berensel

March of Women (Marcha de Mujeres), 2018

27’

March of Women focuses on the 1977 Bakırköy Sümerbank Strike by TEKSİF (a women textile workers’ union), which had been shot and documented in 16 mm by women.

Marcelo Expósito con Nuria Vila

Tactical Frivolity + Rhythms of Resistance (Frivolidad Táctica + Ritmos de Resistencia), 2007

39’

Created in 2007 as a contribution to non-global movements, Tactical Frivolity + Rhythms of Resistance is part of the series Tra i sogni: Saggi sulla nuova immaginazione politica (Among Dreams: Essays on the new political imagination), created by Expósito in the 2000s to portray the expressive forms of social movements against neoliberalism. The video embodies a revolutionary character; it is disobedient and determined to challenge and desacralise all those protest actions that have been considered anarchist, both in the past and present. Through its documentary style, Tactical Frivolity + Rhythms of Resistance captures all those “frivolous” practices, all those micro-actions of social struggle that instill fear in those in positions of power. The work documents the protests of the British group Earth First! against the annual meeting of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank in Prague, in September 2000.

The video shows people dressed in pink, with balloons and feathers, dancing in the streets, reclaiming places, spaces and identities with radical actions. There is a story of 67,000 people dressed in pink and silver taking to the streets and uniting as a dancing movement, determined to make their voices heard and express their disobedience. However, the video also reveals much more. It shows the violence of the police, who respond to the dancing march with violent, punitive and repressive actions. The images of the protest in pink are interspersed with short interviews, capturing testimonies of the violence. The images, together with the sounds, become a powerful instrument, a choral anarchist action, which underlines how street demonstrations can become the manifestation of desire, a moment of protest.

Tactical Frivolity + Rhythms of Resistance pays homage to the practices of social frivolity and is a tribute to the anti-globalization, feminist and ecological movements of the 1990s that anticipated the traits of the present ecofeminist and queer movements.

Carlos Motta

Corpo Fechado – The Devil’s Work (Cuerpo cerrado - La obra del Diablo), 2018

24’33’’

Corpo Fechado: The Devil’s Work is a historical documentary and filmic poem that interprets the story of José Francisco Pereira, an enslaved man who was tried by the Lisbon Inquisition for sorcery and sodomy. An adaptation of Pereira’s trial is interwoven with passages from Saint Peter Damian’s passionate 11th-century condemnation of sodomy as an unrepeatable sin in Letter 31 (also known as The Book of Gomorrah), and Walter Benjamin’s iconic elucidations on historicism and progress in Theses on the Philosophy of History. The film revisits the morally and legally charged figure of the sodomite as a violent historical construction and expression of ecclesiastical, institutional, and colonial patriarchy.

In 1731, José Francisco Pereira, a slave from Judá, Costa da Mina, was tried by the Lisbon Inquisition for sorcery. Pereira confessed that together with fellow slave José Francisco Pedroso, he made and distributed bolsas de mandinga, amulets to protect slaves from wounds both in Brazil and Portugal. He also confessed to have made pacts with male demons and engaged in copulation with them. Pereira was thus also charged with sodomy, exiled in the galleys as a slave rower, and forbidden to enter Lisbon forever.

In 1049 Italian monk Saint Peter Damian composed Letter 31 to Pope Leo IX condemning sodomy and all acts against nature committed to satisfy sexual pleasure beyond procreation – like masturbation, inter femoral fornication and anal coitus – as unrepentable sins. The Saint passionately implored the Pope to eradicate this widespread sin within the clergy through legal and theological arguments, eventually describing the spiritual condition of the damned Sodomitic soul. Letter 31 arguably established the subsequent historical position of the Catholic Church against homoerotic sexual practices by categorizing them and placing them at the bottom of the moral and legal orders.

In Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940), Walter Benjamin critiques historicism and the notion of the past as a continuum of progress. He introduces this critique with the metaphor of the angel of history, a figure whose face is turned towards the past, with its wings caught up in a storm, unable to look into the future. In the essay Benjamin explains the framework of modernity pointing out how society has constructed "progress," an illusion in which old systems endure and are propelled forward by a promise of a better future.

In Corpo Fechado The Devil’s Work the three chronologically distinct accounts are layered to contest the violence exerted by the colonial Catholic Church to promote a singular theological model and the creation of forms and languages of sexual oppression and the subjectivities they perpetuate.

Güliz Sağlam 8 Mart 2018 – Istanbul / 8th of March (8 Mart 2018 – Estambúl / 8 de Marzo), 2018

6’

From 20 March 2021 onwards, feminist and LGBTQ+ rights movements have been actively protesting to protect the Istanbul Convention (an international treaty against gender-based violence and domestic violence, approved by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe in 2011 and signed in Istanbul by 45 nations) by occupying the streets in many provinces across the country. Some of Güliz Sağlam’s recent videos document the protests that took place in Tünel (Istanbul, Turkey), against Turkey’s exit from the Istanbul Convention on 1 July 2021, against the patriarchal state. Hundreds marched and chanted slogans such as “Women are strong when they are united” and “Immediate action against femicide, now!”, among others. For example, the video 8 Mart 2018 – Istanbul / 8th of March 2018, filmed a few years earlier, captured a powerful display of solidarity from women and members of the LGBTQ+ community who occupied Istiklal Caddesi, one of the most popular and lively streets in Istanbul, for International Women’s Day. Protesting has always been one of the most direct and effective means of vindicating struggles and denouncing injustices and abuse: many individual voices, silenced and unheard, become a single powerful collective voice. A transfeminist tide occupied the road from one end to the other. The video shows a banner with the words “Our life, our revolt, our struggle: feminism” held by the front rows of the crowd, which alludes to the length of the procession.

This was the last time a feminist protest could be organized on Istiklal Caddesi because the government banned this type of protest in 2019. But, in actual fact, alternatives were quickly found to continue demonstrating around Istiklal Caddesi, thus avoiding the government’s restrictions. Sağlam, following the example of 8 Mart 2018 – Istanbul / 8th of March 2018, will continue to make films inspired by protests (such as 8 Mart 2021 - Istanbul Feminist Gece; 8th of March 2022 – Istanbul...) which, together, tell the story of difference and oppression and repression depending on local and global circumstances in recent years.

Seba Calfuqueo

Nunca serás un Weye / You Will Never Be a Weye, 2015

4’46’’

In Mapuche culture (Amerindian people from central and southern Chile and southern Argentina), gender has a bearing onspiritual practices, visibly for example through the Machi. Traditionally, the Machi are predominantly women revered as healers and spiritual guides, symbolising a bridge between the mundane and the divine and offering guidance and remedies to their communities. However, there are also male healers, known as Machi Weye or Ngenpin, though less common. Gender roles within Machi culture reflect a dynamic balance in which men and women contribute to the spiritual and social fabric of society. This emphasises the resilience and adaptability of Mapuche traditions in dealing with contemporary conceptions of gender.You Will Never Be a Weye is a video performance by Chilean artistə Seba Calfuqueo inspired by the ancestral culture of the Machis Weyes, which, despite its vital role, was historically concealed after the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores on Chilean soil, and not accepted by the imported models of society, religion and patriarchy, despite his vital role for Mapuche people. Archival documents on Machis Weyes culture are almost completely non-existent, yet they are reported in the 1673 book El Cautiverio Feliz by the Spanish writer Francisco Ñúñez de Pineda y Bascuñán. In this book, he states referring to a Machi Weye: “He resembled Lucifer in features, size and costume. He wore no underwear because he was of those called hueyes”.

The artist stands in a darkened room where the artist slowly dresses in the traditional clothing of the Machis Weyes, slowly recounting personal and historical facts about the Machi Weyes, and sharing the desire to save their identity. Paying homage to his ancestors, Calfuqueo through this video performance attempts to reclaim an identity that has been brutally erased.

Sara Jordenö

Kiki, 2016

93’48’’

In the late Seventies, in New York City, the protagonists of the black/black LGBTQ+ scene gathered on the Christopher Street Pier, practicing a performance-based art form, the Ballroom, made famous a decade later in the early Nineties, by Madonna’s Vogue music video and the documentary Paris Is Burning. Twenty-five years after these cultural milestones, a new and very different generation of LGBTQ+ youth has formed an artistic and activist subculture, called the Kiki Scene. The term ballcultureidentifies a subset of New York's LGBT culture - a term in use until the 1990s - of dance competitions that unite African-American gays, Hispanics and transgender people, parading in 'drag', i.e. dressed in clothing from the opposite gender.

Kiki (Kiki, or alternatively kiking or ki, is a term that originated within ball culture and is used by the LGBTQIA+ community as an informal term indicating a social gathering mainly for gossip or general fun) follows seven characters from the Kiki Scene over the course of four years, using their preparations and spectacular performances at events known as Kiki Ball as a framing device while they delve into their struggles (such as homelessness, illness, and prejudice) and their subsequent political achievements. The Ball offers artists a safe space to express themselves freely, unlike the repressive and potentially violent places they grew up in – many of them were in fact kicked out by their families of origin and, as black LGBTQ+ people, are a minority within a minority. The Kiki scene was created within the community as a peer-led group offering alternative family systems (Houses). The scene then evolved into a major (and ever-growing) organization with rules, leaders and teams that govern it, which now has hundreds of members in New York, the United States and Canada.

In this cinematic collaboration between Kiki Gatekeeper, Twiggy Pucci Garçon and Swedish director Sara Jordenö, viewers are granted exclusive access to this high-stakes world, where fierce Ballroom competitions serve as a pretext for conversations about the Black and Trans movements. Lives Matter. This new generation of young dancers uses the motto “Not About Us Without Us” and Kiki was made with extensive community support and trust, including a soundtrack from renowned producer collective Ballroom and Voguing Qween Beat. Twiggy and Sara’s insider-outsider approach to their stories breathes new life into the portrayal of a marginalized community demanding visibility and real political power.

Simone Cangelosi

Una nobile rivoluzione: Ritratto di Marcella Di Folco (Una noble revolución: Retrato de Marcella Di Folco), 2014

83’07’’

A Noble Revolution: Portrait of Marcella Di Folco was inspired by the similarities shared by the stories of Simone Cangelosi and Marcella Di Folco, who was the first transgender person in the world to hold public office. The film is a documentary that retraces Marcella’s life through a montage that combines images of her public and political life, describing her as a remarkable woman who has lived multiple lives.The work begins in Rome, Marcella’s hometown, during the years when she worked at Piper, a historic nightclub in the capital. In that period, Marcella began to affirm her identity and live a life of liberty. After being noticed by Federico Fellini, she began her film career starring in Satyricon (Fellini, 1969). Over the years, she has never hidden her homosexuality, and the pivotal moment occurred at the Paradise nightclub when the Carrousel de Paris, a group of trans performers with whom Marcella had formed a close friendship, performed. This relationship gave her the necessary security to begin her path of transition and in 1980 in Casablanca she underwent surgery. Upon returning to Italy, she moved to Bologna and joined MIT (Movimento Identità Transessuale [Transsexual Identity Movement]), participating in the protests that led to the approval of Italian Law no. 164 (dated 14 April 1982, was the first law in Italy to introduce the possibility of gender reassignment). Following this, Marcella took an active role as an advocate and supporter within MIT, ultimately assuming the role of President in 1988. Under her leadership, the movement gained new impetus and she pioneered a gender identity advisory centre, the first of its kind to be run by transgender individuals. This centre continues to operate today as part of Bologna’s local health services.In 1995, she became a City Councillor of Bologna with the Green Party. A few years later, in 1998, she met Simone Cangelosi. “I never imagined that she would become my friend, nor that she would become a point of reference for me,” says the director, but what was clear from their first meeting was that he was “in front of a historical figure”.

Pedro Lemebel

Desnudo bajando la escalera, 2014 (2’10’’); Pisagua, 2006

3’29’’

“I have always used fire and neoprene, for all the symbolic load that that flammable glue has since the times of the dictatorship: toluene against hunger, unemployed young people, the barricade, the Molotov heart, until now (that meaning) is strengthened again in the burned street of the student march.”

(Pedro Lemebel)

Neoprene is a solvent that, since the 1970s, has been used as a medicine by marginal communities, especially minors. Pedro Lemebel chooses to work with neoprene to evoke the ghosts of the hungry, of the kids who inhaled it on street corners and of those segregated by the neoliberal state. As a flammable material, however, it is also used as a symbol of resistance to the patriarchal hegemonic system. On February 11, 2014 at 5 in the morning, in front of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Santiago de Chile, Lemebel performs Desnudo Bajando la Escalera. The title of the action is a clear reference to Duchamp, but while the latter broke down perception, Lemebel breaks down linear time through a series of quotes and references. The performance alludes to emblematic cases of human rights violations during the Chilean dictatorship. The place in front of which Lembel performs is the same as Yeguas Del Apocalipsis (the art collective founded in the late 1980s by Francisco Casas and Lemebel himself) second public appearance in 1988. The country is certainly not the same, and neither is Lemebel. The artist, however, performs an embodied analogy: his body takes the place of those that have disappeared, and by returning them to the public sphere, he showcases the repression and violence of state terrorism.

“But do you have any idea where they will take us? Gastón asked, furrowing his plucked eyebrows. It’s a military secret that I can’t tell you. And get a move on, we have little time (...). But I need to know if it’s the North or the South, if it’s cold or hot, to decide what clothes to bring. I think it’s up to you to go to the North, the soldier told him dryly. But in which area of the North? Beach or mountain range? In Pisagua, it seems. So it’s beach, sand, sea and sun, thought Gaston, grabbing his swimsuit and a towel.”

(Pedro Lemebel)

Due to its isolated position between ocean and desert, the small port of Pisagua, in the north of Chile, is unfortunately known for having been transformed into a concentration camp and port of exile for political dissidents during dictatorial regimes. The 2006 video Pisagua was shot by director Veronica Quense, when the latter went with Lemebel to visit the city and collect the testimonies of the residents. The result of their experience is this action in which the artist walks barefoot, holding his heels in his hand, towards the sea. With every step he takes on the white cloth Lemebel leaves behind faint blood-colored footprints: a tribute to all the homosexuals and dissident feminists who lost their lives in that place.

RADICAL ECOLOGIES

Oliver Ressler

The Path is Never the Same (El camino nunca es el mismo), 2022

27’

This film focuses on two complex, self-organizing systems: a forest and an occupation.

Long shots capture the Hambach Forest near Cologne, one of Germany’s last old-growth forests. The forest has become the site of Europe’s longest tree-top occupation. Since 2012, around 200 people have been living in the forest to prevent its clearing by the energy company RWE, which seeks to extract the lignite beneath the forest floor.

By January 2020, much of Hambach Forest had already been destroyed, but sustained pressure from climate activists over the years forced German politicians to order the preservation of what remained. The film reflects on the forest as a living space and on the urgent need to confront the climate vandalism carried out in the name of “economic activity.”

The people here organize non-hierarchically, standing— as one activist in the film puts it—“just like the trees, next to each other, on the same level.”

Sanjay Kak

Words on Water, 2002

85’

The documentary looks at the effects of the Sardar Sarovar Dam (the largest one in the Narmada Project involving the construction of 30 large, 135 medium-sized and 3000 small dams in Gujarat and other parts of Central India) and the millions of people who will be adversely affected by this project sponsored by the World Bank and the Central Government of India.

For more than two decades the shores of the Narmada River in central India have been the sight of extraordinary struggles for human dignity. Inhabitants of the Narmada Valley have organized a unique popular movement - protesters are the hundreds of thousands of people who have been displaced after the construction of 30 dams along the river, and abandoned by the Indian government, which has failed to provide new housing for the victims.

Critical Art Ensemble

Radiation Burn: A Temporary Monument to Public Safety (Quemadura por radiación: un monumento temporal a la seguridad pública), 2010

12’30’’

The work deal with the fear of the so-called ‘dirty-bomb’, described as a real threat in the context of global terrorism and implemented as a means to legitimize relationships of power. The video evokes the image of Japanese citizens engaged in the daily acts of amateur risk assessment imposed upon them by the failures of the corporate state.

Ravi Agarwal

The Flower Pluckers (Los Recolectores de Flores), 2007

3’33’’

Ancient Tamil Sangam akam love poetry, is one, where five landscapes, Kurinji (mountains), Mullai (forests), Marutam (agricultural lands), Neytal (sea), and Palai (desert), reflect an internal terrain of feelings – of sexual union, yearning, sulking, pining, and separation. The poems, from a literary tradition in old Tamil, suggest other ideas of nature, where the subjectobject co-form each other. Nature has been reduced to an object which can only be ‘acted’ upon through it being ‘extracted,’ ‘admired,’ ‘enjoyed,’ etc. but not ‘lived’ with. The relationship is one of power. Capital, technology, mass production, resource exploitation, have all prospered though this positioning. Wilderness has been privatized, forests fenced, rivers tamed, and animals made extinct. No one can guarantee future survival.

Mao Chenyu

I Have What? Chinese Peasants War: The Rhetoric to Justice (¿Tengo qué? Guerra de los campesinos chinos: la retórica a la justicia), 2013

103’

The essay film I Have What? Chinese Peasants War: The Rhetoric to Justice examines China’s agricultural discourses and the status of capital in the past several decades through regional samples. It investigates issues including how the land system may acquire equality and efficiency as well as the loss of divinity in the relationship between the peasants and the land. Meanwhile, the film also attempts to expand the vocabulary of the land and farming. As the artist was tracing the land and the relics of past beliefs, he also interviewed more than a hundred peasants in a dozen village communities. In front of the camera, the peasants either soliloquized or sit by one another to discuss current social affairs, their hypotheses of things, and anticipations, thus re-sharpening certain concepts that had once become inertia thinking through personalized expressions of emotions and narratives. The film also discusses the relationship between introduced species and the severe drought in Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau as well as the changes in the “rationality” of local governance.

Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée (AAA)

Au Rez-de-chaussée de la ville (En los bajos de la ciudad), 2005

34’

ECObox is an urban social experiment started in 2001 in La Chapelle, in the North of Paris. It aims to use temporary and under-used spaces for collective activities. It brings together the knowledge of architects, artists and researchers and the knowledge and skills of local people, in a collective who acts through ‘urban tactics’, strategies self-re-presented by AAA in this documentary.

Karrabing Film Collective

The Family & The Zombie (La familia y el zombie), 2021

29’23’’

The Family and the Zombie, 2021 (Karrabing Film Collective) interrogates the current ecological crisis and the indigenous and cultural destruction that colonialism has produced in Northern Australia. The film opens with a group of future ancestors digging for sweet potatoes while their children play. Alternating between contemporary times, in which the Karrabing members struggle to maintain their their physical, ethical and ceremonial ties to their remote ancestral lands, and a future peopled by ancestral beings living in the aftermath of toxic capitalism and white zombies, the film rejects the colonial clock in which the past is buried in the inexorable domination of the future.

INSURGENT COMMUNITIES

Khaled Jarrar

The Infiltrators (Los infiltrados), 2012

70’

The film unravels adventures of various attempts by individuals and groups during their search for gaps in the Wall in order to permeate and sneak past it. Lookouts, fear, angst, running, permeation, jumping off, crawling, passing through dark passages are stages of a complex process of passing through to the “other side” and require a very specific state of mind. Some attempts end in failure, and others in success. Some are caught by the Israeli soldiers, and others reach their destination. It’s a cat-and-mouse game.

Paloma Polo

El barro de la revolución, 2019

120’8’’

What social conditions give rise to political change? This question propelled Polo’s immersion in the revolutionary movement in the Philippines. The work, coexistence, and filmic inquiry she undertook in a guerrilla front were the culmination of three years of research and reflection as she engaged in the political struggles of this country.

For more than five decades, the initiatives directed by communist communities in the Philippines have been neglected, censored, and often violently repressed due to their wilfulness to implement alternate socio-political and cultural modes of existence. The bonds she forged within these communities, and her subsequent commitment and solidarity with their struggle, facilitated her later integration in a guerrilla unit on the basis of her film project.

Building the revolution in the Philippines means growing collectively and singularly. The revolution advances to the extent that revolutionaries cultivate themselves and flourish, managing to effectively transform a common world. The work of the members of the NPA (New People’s Army), the armed branch of the Communist Party, is founded on three main pillars: 1_building up their organs of self-governance (“base building”), 2_ the implementation of agricultural revolution (to different degrees, depending on the region), and 3_military combat.

The ongoing Philippine struggle adheres to the communist tradition and is rooted in the revolutionary liberation movements that have combatted the colonial yoke for centuries. A strenuous revolutionary force emerges from the poorest communities, which are wilfully fighting to eradicate the ills that, from the revolution’s perspective, continue to ravage the country: a semi-colonial and semi-feudal society plagued with capitalist bureaucrats and relegated to a deindustrialization that forces the estate to consume imported merchandise and to continuously exploit cheap labour, while the plunder of natural resources orchestrated by international corporations in alliance with the government is rampant. An intense militarization and state repression render the Red zones almost inaccessible.

The NPA members that are featured in the film are not only guerrilla fighters, they are industrious and active builders of an alternate world, born out of cooperative work. Daily life in the camp is organized around educational and pedagogical projects, which are reinforced by the collective assessments. Their task is largely pedagogical, but they also serve entire communities as doctors, teachers, researchers, artists, mediators, administrators, farmers… This transformative process, gradually and existentially modelled as it surmounts setbacks and obstacles, can only take place and can only be thought if it is always in the making. In this sense, large swathes of remote rural regions have become a sort of laboratory of life.

Ali Essafi

Wanted (Al-Hareb) (Se busca (Al-Hareb)), 2011

20’

Ali Essafi’s short film Wanted (2011, 24’) attempts to fill three gaps, three invisibilities in the history of Moroccan cinema, from which he has suffered in his personal construction as a filmmaker: he replaces the ‘missing images’ of the political repression of the 1970s in Morocco with little-known, or even censored, images. In this way, he follows, paying homage to Ahmed Bouanani’s approach as a bystander, re-establishing the possibility of cultural transmission between generations despite colonial and post-colonial ruptures, and extending his research to a cinema whose forms reactivate traditional oral practices. In the 1970s, Moroccan schoolboys and students dreamed of freedom and democracy. Severe police crackdowns on dissent and wide arbitrary arrests, detention, and secret prisons have branded the decade as the ‘years of lead’. A number of activists lived in clandestinity. Aziz was twenty-three years old at the time, he was lonely and carried a false identity for two years before he was identified and arrested.

Grupo de Arte Callejero

Aquí Viven Genocidas, 2001 (10’); Invasión, 2001 (3’); Poema visual para escaleras. Estación Lanús, 2002 (3’); Ministerio del Control. Plan Nacional de Desalojo, 2003 (2’); Shopping para artistas, 2003 (1’); Desalojarte en progresión, 2003 (1’)

Libia Castro & Ólafur Ólafsson

Aðfaraorð / Preamble (Aðfaraorð / Preámbulo), 2020

5’06’’

Roy Samaha

Transparent Evil (Mal transparente), 2011

27’

Late 2010, I got commissioned by Leica to follow in the footsteps of James Bruce (a Scottish explorer who set to discover the source of the Nile between 1768 and 1773). I got interested in that project because it had the nature of a time travel. So I was set to document the Nile River from Alexandria to Aswan. January 25, the revolution started in Egypt. The only incoming images so far were made by protesters with cellular phones and uploaded on the net. They were much more efficient than the state owned television station which was still doing the pro-regime propaganda in high definition resolution. I understood that there was no point in making the same pictures that were out there. This is the ecstasy of communication this is the electronic revolution. “Every revolution is a technical one”. The Invisible Generation is everywhere.

Chto Delat

Partisan Songspiel. A Belgrade Story (Canción partisana. Una historia de Belgrado), 2009

29’15’’

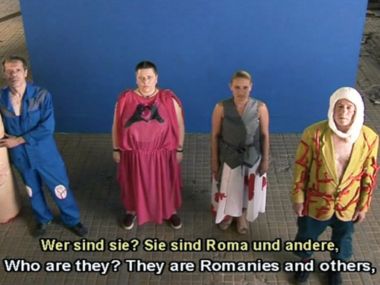

The film presents an analysis of a concrete situation: Partisan Songspiel begins with a representation of the political oppression (forced evictions) the government of the city of Belgrade visited on the Roma people inhabiting the settlement of Belleville, on the occasion of the summer Universiade Belgrade 2009. It also addresses a more universal political message about the existence of the oppressors and the oppressed: in this case, the city government, war profiteers and business tycoons versus groups of disadvantaged people − factory workers, NGO/minoritarian activists, disabled war veterans, and ethnic minorities. At the same time the film establishes something that we can call the “horizon of historical consciousness,” which is represented through the choir of “dead partisans” who comment on the political dialogue between the oppressors and the oppressed.

Etcétera / Movimiento Internacional Errorista

FAKE NEWS – El club del helicóptero, 2017

7’06’’

Mohanad Yaqubi

R21 aka Restoring Solidarity, 2022

71’

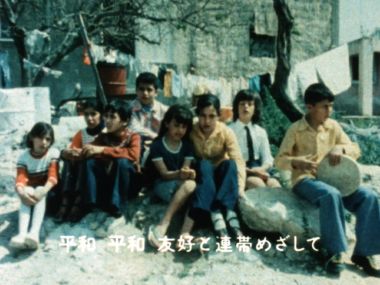

R21 comes as an addition to and a reflection on a collection of 20 16mm films, safeguarded in Tokyo by the Japanese solidarity movement with Palestine. It’s an undelivered solidarity letter written by a Japanese activist that was lost on its way to a Palestinian filmmaker. Fragments of the letter are found throughout the collection and compiled into an imagined structure that reveals itself during the film.

R21 aka Restoring Solidarity acts as a catalog, the film as a time machine, the film as an archive. The themes that Reel no. 21 deals with, reveal themselves in the form of a montage essay. At the same time, the act of restoring these films brings out motives, aspirations, and the disappearance of a generation and its struggles, not only in Japan, but around the world.

DIASPORA ACTIVISM

Atelier Impopulaire

Before We Love, Act 2: 12 Gates (Antes de amar, Acto 2: 12 Puertas), 2024

30’

12 GATES is the second act of BEFORE WE LOVE, an opera in three chapters inspired by the UMBRA Poets Workshop (1961-63) that completes Atelier Impopulaire’s trilogy about the birth of underground artistic movements and civil rights activism in the Italian, African-American, and Latino communities that had migrated to New York City’s Lower East Side by the early 1960s.

In this instance, 12 GATES manifests as a single-channel video that is part of a large-scale multimedia installation. It integrates rare archival material with Atelier Impopulaire’s new footage, drawing on UMBRA’s literature to explore the fight against cultural oppression by movements advocating for social justice through multidisciplinary practices.

The installation follows the principle of non-chronological chronicle, faithful to the idea of Tom Dent - founder of the group - of generating a deconstruction of the “historical truth”of the narrator's singular point of view. The video thus becomes a pluricultural fragment, serving as an agent of meditation on history, where elements of contemporary visual languages function as a counterpoint, intertwined in a narrative that combines film works, poetry, and abstraction.

Ursula Biemann

Sahara Chronicle (Crónica del Sahara), 2006–2009

33’14’’

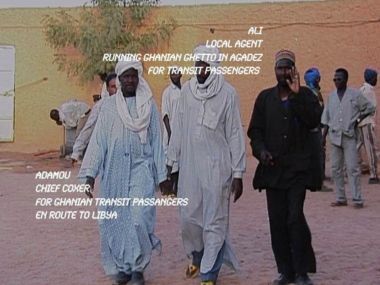

Part of the larger project The Maghreb Connection, on the policy of mobility and containment of migration flows in the Maghreb, the anthology of 12 video-narratives Sahara Chronicle, made between 2006 and 2009, was realized during the artist’s countless journeys between the main stopping points of the trans-Saharan migratory network of Morocco, Niger, and Mauritania. It is a film-essay that narrates migration as a collective experience in its systemic dimension, focusing on one hand on the attempts made by different authorities to contain and manage these movements, and on the other hand on the story of how people move across the Sahara and the struggle for migratory autonomy. These movements have generated prolific operational networks, systems of information and social organization among migrants and interactions with local populations. The film presents the migration system as a set of pivotal sites, each of which has a particular function in the struggle for migratory autonomy, as well as in the attempts made by different authorities to contain and manage these movements.

Sahara Chronicle highlights how migration policy in Africa has changed in the direction of progressively reducing freedom of movement between borders. Cooperation agreements with the EU have delegated the management of trans-Saharan movements to the Maghreb states (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya), outsourcing border control to countries where the flow of people had been free for decades. The visa requirement for travelers entering the Maghreb from the south now makes it illegal to cross a territory that most people considered their legitimate area of mobility.

El Chinero, un cerro fantasma, 2023

11’

LIMINAL & Border Forensics

Asymmetric Visions (Visiones asimétricas), 2023

10’54’’

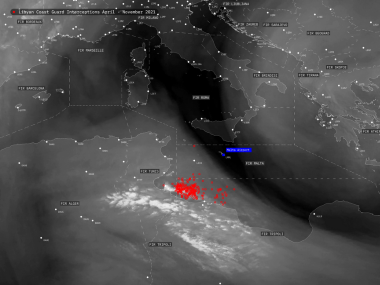

The film unfolds above the murmuring waves of the central Mediterranean, where the drama of survival plays out on the stage of the sea and sky: immigrant vessels, specks in the deep, moving under the gaze of mechanical hawks.

The aerial specters weave a tapestry of surveillance along the maritime border, pioneering the imagination, outlining the vision of sovereignty and order. The detached rhythm of surveillance drones hums in the silent air, casting long shadows on the blue surface of the water in this liminal zone where hope and despair dance together; this indifferent violence casts a deep shadow on the blue surface, its silence more piercing than the primal cries for survival aboard migrant vessels. Yet, these cries are frozen and isolated in front of distant screens, transformed into silent images, silencing the despairing will to live. Are the red dots at sea life jackets or flames?

Border Forensics employs cold images and technology to present us with an unknown narrative: a whisper rejecting the portrayal of humanity, a resilient spirit thriving beyond the reach of distant observers, evidence of a persistent journey for dignity under the relentless gaze of the sky. This modern technology plays a lament for deferred dreams. As the ghosts of technology glide through the sky, they mark the boundaries between the visible and the invisible, the saved and the abandoned. Their traces are etched between sea and sky, narrating journeys beyond borders, entwined with the fate of relentless waves.

Angela Melitopoulos

Passing Drama (De paso por Drama), 1999

66’14’’

Passing Drama is a multi-voice diary recounting the intertwined migration path of the inhabitants of Drama, a small town in northern Greece still inhabited by refugees who survived Nazi deportations. During the Second World War, many inhabitants of Drama were forced to exodus to labour camps in Nazi Germany, and not all of them returned to their hometown. This migratory and diasporic fate is common to the parents of Angela Melitopoulos (who was in fact born in Germany) and to entire generations of refugees, involved in a progressive cracking of collective memory, the restoration of which is attempted by the dense visual and sound texture that the artist restores in the film. Conceived as a veritable “video texture”, Melitopoulos thus restores the migrant history of her own family, emphasizing how the experience of diaspora undermines any order of perception of subjective memory. This idea of oblivion is expressed through an interwoven montage of images that reflects the deforming action of time: the older the events, the more the montage of images has undergone manipulation. The repeated fragments of industrial looms that appear between the sequences provide not only sociological representations (many refugees did in fact work in the textile industry), but also reflect the actual “textile-urological” paradigm of the film’s narrative construction.

Pınar Öğrenci

Inventory 2021 (Inventario 2021), 2021

16’

Inventory 2021 by artist Pınar Öğrenci is a remake of the original film Inventur-Metzstrasse 11 shot by Yugoslav director elimir ilnik in Munich in 1975. In this second version of his film, set in the city of Chemnitz and shot in 2021, Öğrenci offers an alternative look at the situation of people of different genders, ages and ethnicities living in Germany as immigrants. As in the original work, the filming takes place inside the building where the people are supposedly staying, who, one after the other, introduce themselves to the camera by briefly telling who they are and how they live their situation as immigrants.

Pınar Öğrenci, however, offers a contrary perspective to that of elimir ilnik: the 1975 film depicted an inhospitable and difficult situation for most of the foreigners, foreshadowing a progressive decay of their conditions, metaphorically rendered through the movement of descending stairs. In contrast, Inventory 2021 illustrates a situation of well-being and progressive improvement in the lives of the immigrants. The interviewees declare themselves satisfied with their daily life in Chemnitz, they manage to perceive it as permanent rather than precarious and, once their story is over, they leave the scene by climbing the stairs rather than descending them.

With a decolonial and anti-racist slant, Öğrenci’s film thus promotes a positive approach to immigration, reformulating the concept of home, no longer linked only to contingent circumstances but a place of authentic and rooted life even for those who find themselves living in a context different from their own. With Inventory 2021, Öğrenci conveys confidence in the capacity for integration and inclusion of what was once considered foreign, emphasising the enriching potential of diversity in the contemporary world.

Daniela Ortiz

No es un hueco en mi tierra la raíz que arrancaste; es un túnel!, 2024

30’

Tita Salina & Irwan Ahmett

B.A.T.A.M (Bila Anda Tiba Akan Menyesal) - When You Arrive You’ll Regret (B.A.T.A.M (Bila Anda Tiba Akan Menyesal) - Al llegar te arrepentirás), 2020

43’01’’

“Exiles, refugees, undocumented migrants – regardless of the word we use, the movement of human beings across the planet is a millenary and repetitive story. It follows the evolutions of our civilizations, the catastrophes and sometimes the downfalls”.

Following an archaeological dynamic, Bani Khoshnoudi reflects on social reactions towards human migration movements. She delves into a contemporary context, exploring the displacement of peoples – Transit(s) – through the traces they left behind.

The director closely examines the complexities of these experiences of change, offering an intimate perspective on the lives of individuals. She addresses the fluidity of their identities, reflecting their emotions, internal conflicts, and relationships, as they navigate the difficulties of being “foreigners” in a place that may not fully accept them.

Transit(s): Our Traces, Our Ruin stands out for its ability to convey universal messages, thanks to its artistic sensitivity in recounting both personal and collective experiences. It is a work that invites reflection and empathy, posing important questions about the dynamics of contemporary societies and the challenges faced every day in the search for belonging and identity.

Sim Chi Yin

Requiem (Internationale, Goodbye Malaya [Réquiem (Internacional, Adiós Malaya)], 2017

6’08’’

Requiem depicts now-elderly former communists reclaiming memories of their political participation, war, deportation, exile, and socialist dreams, in the form of song. In their youth, they were guerrilla fighters who took on the British in the jungles of Malaya (present-day Malaysia and Singapore) in the anti-colonial war of 1948-1960. In poignant moments, the veterans struggle to remember lines from the global socialist anthem they sang daily 70 years ago, the Internationale – which their death row comrades had sung in defiance as they were marched to the noose to be hanged. Goodbye Malaya, composed and scored by a pair of Malayan communists in 1941, was belted out en masse on the decks of the ship as the leftists were deported from their homeland, and in many cases, the country of birth. Over 30,000 Malayan leftists – including the artist’s paternal grandfather – were deported by the British to China during the so-called “Malayan Emergency” (1948-1960), a war that followed Britain’s rule in Palestine and preceded America’s war in Vietnam. Their stories are largely missing in the historiography of this war – the longest the British fought post-World War II. Like memory itself, their voices are sometimes fragile, fallible, but also resilient.

THE DISOBEDIENCE ARCHIVE

Interview with curator Marco Scotini during the Istanbul Biennial

(fragments)

Arts of the Working Class exchanged written correspondence with Scotini on the eve of an event many expect to shift fundamental ideas about art curating and its circulation.

Arts of the Working Class: What are “disobedient images,” and how are they framed within the Archive?

Marco Scotini: Disobedient images do not conform to the norms of any single, exhaustive cultural category. They are multiple, heterogeneous, polyphonic, and resist definitions that codify and objectify the spaces of art and politics. Their refusal to obey asserts itself as a force of creation and experimentation—of languages, devices, institutions, and subjectivities.

What matters is what and whom these images disobey. If they challenge the colonial aspect—never neutral and always technologically mediated—of audiovisual language, and if their purpose is to reveal precisely what corporate media tries to hide or erase, then they reclaim control over the violent expropriation of experience and, in doing so, produce and make history visible. History, understood as a problem of political representation, lies at the center of these films and videos. This “disobedient cinema” embodies a strategy of action that cuts across the canonical divisions established by “power”—such as environment, bodies, psyches, labor, society, and semiotic flows—to intervene in life itself.

These images function as profaning devices and claim an experimental potential against political directives or mandates. They map a politics of immanence—never given once and for all, but constantly conquered through the pragmatics of experience. For this reason, Disobedience Archive is not only a record of struggles and protests, but also an archive of imaginaries, ways of living, production, seeing, learning, and self-representation.

Arts of the Working Class: Does the Disobedience Archive occupy spaces opened up by contemporary art in order to influence the organizational capacity of communities toward political action?

Marco Scotini: The Disobedience project is an inquiry into artistic activism practices that emerged after the end of Modernism, inaugurating new ways of knowing and acting.

A different relationship between art and politics characterizes the current phase of capitalism, in which it is impossible to understand radical societal changes without considering the transformation of languages that have been and continue to be produced—both as political subjects and as mediated objects.

Indeed, Disobedience Archive operates within this social terrain, located at the core of subjectivity production, where there is no longer a separation between the flow of signs and the flows of material or force. The archive aims to act as an activator of the present in terms of social change and as a collector of countless experiences of insubordination as a shared force.

Arts of the Working Class: There is a passage in the main document of the Disobedience Archive (The Park) that says: “Every mobile phone now holds the power to defy, to become narrative.” In comparison, how does the art world's labor force represent a movement toward class consciousness? And how does it fail to do so?Marco Scotini: Fortunately, there is no single “art world.”

However, within the art world, a deeper problem exists today—one that, since the financial crisis, arguably stems from the fact that a new neoliberal threat has captured libertarian aspirations and extracted value from the terrain of social demands that should have opposed it. It has neutralized and reabsorbed every fracture into the realm of expression alone, without damaging power relations.

Source: https://artsoftheworkingclass.org/text/the-disobedience-archive

The Disobedience Archive at the Venice Biennale

(fragments)

by Elvira Vannini

Addressing the theme of geographic, ethnic, and identity displacement raised by Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, Disobedience Archive introduces two new sections: “Diaspora Activism” and “Gender Disobedience.” These operate as alarms, pointing to a critical position that Scotini seems unwilling to relinquish: an anti-capitalist trajectory for negotiating freedom against imposed mandates, where the concept of autonomy applies to those who practice rupture.

Disobedience manifests across different latitudes and historical moments, tracing the transformations of post-1968 movements (which, as Foucault notes, became transversal rather than identity-based or hierarchical) through to the most recent uprisings. It reaffirms the urgency of new spaces for political imagination and organization—spaces where politics is never separate from aesthetics.

Themes Addressed by the Disobedience Archive

Disobedience creates a trajectory of escape by refusing to separate decolonization from capitalism (understood as an economic system deeply entangled with colonialism, class exploitation, sexism, and racism). It does not merely represent; it interrogates the epistemic and political positioning of the subjects who speak and the struggles they lead. Disobedience is choral, insurrection is collective, and the modes of organization are associative and assembly-based.

Thus, the focus cannot be on individual artworks. Replacing pluralism with multiculturalism risks weakening the conflict over self-determination and the identities of dissenting subjectivities involved in this grand epic narrative.

What happens when the artist is “authentic”? When a foreigner speaks about foreignness and otherness? When non-Western women, Indigenous, or queer individuals speak of their own experiences?

It is certainly right for women, lesbians, travestis, queers, trans, and non-binary people to occupy these spaces. But there is a danger in the essentialist myth of authenticity, which turns the native into a “reliable informant.”

Including foreign, marginalized, outsider, queer, and Indigenous artists is not enough to decolonize the exhibition within the ordered garden of the Biennale—because, as Fanon reminds us, decolonization is a program of absolute disorder.

Foreigners in Disobedience Archive: Queerness and the Anti-Colonial Discourse

Disobedience responds with a gesture of collective rupture that generates a heterotopic structure—one in which all social spaces are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. This results in a centrifugal diffusion of dissent, opposing the production of the other (anti-colonial) discourse to the reproduction of the Other’s (recolonial) discourse.

Power and Disobedience

(fragments)

The adage by sociolinguist Max Weinreich, that “a language is a dialect with an army and a navy,” reveals the contingency of power. There is an inherent contradiction in the power exercised by the state: it is language that grants a nation-state the right to uphold a punitive legal framework —with the legitimate use of violence as its backing— and yet, that right to exercise legitimate violence almost always stems from a foundational phase of illegitimate violence or the threat of it. India’s independence was achieved in part through peaceful civil disobedience, but it could not have been sustained without a military and police system aligned with the ruling class.

Given the evident gap between the nation-state as a benevolent provider (as it wishes to be perceived) and as a bully in service of the wealthy (as it often is), it is no surprise that resistance to its authority —or to that of its government— is as constant and global as the changing seasons. What may be more surprising is that we have yet to conceive of a more friendly, honest, and localized social structure. This failure may be inscribed in the very methodology of disobedience.

The exhibition Disobedience Archive (The Republic), held at the Castello di Rivoli in Turin during the past spring and early summer, was the result of nine years of research on forty years of resistance history, carried out by curator Marco Scotini in response to the global anti-capitalist uprisings of 2001–2002 and the repression of the post-Seattle movement through the Patriot Act in the United States and similar legislative processes in other countries.

The show presented a selection of 22 videos from the archive, addressing topics such as education, anti-capitalism, Italian resistance in the late 1970s, disobedience in Eastern Europe and Argentina, the Arab Spring, Reclaim the Streets, gender politics, and Foucault’s notion of “biopower.” The screens were arranged in an amphitheater-like —or “Parliament”— format that invited the audience to investigate the recent history of resistance. This was the first time the archive was presented in Italy and it coincided with a moment of increasing political tension and a growing hybridization between the art world and activist politics.

The simplicity of the traditional “us versus them,” “left versus right,” is certainly a distraction, but there is another dialectic at play that impedes social change on a different level. In Turin, the exhibition included works by collectives such as the Living Theatre, figures like feminists Carla Lonzi and Carla Accardi, and the free radio station Radio Alice from Bologna, all committed to a more complex and non-dialectical vision of society, reflecting the internal conflict of the Italian left at that time and the antagonism between the Communist International and the Situationist Movement in France in 1968.

In Italy, the Bene Comune movement, which firmly links art and activism, is consolidating itself as a national political alternative. In April, Stefano Rodotà, considered the father of the movement, was a presidential candidate in the final vote against Giorgio Napolitano. A deep understanding of history —such as that proposed by projects like Disobedience Archive— can help unlock the antagonisms that prevent each generation from unmasking the deception inherent in state and governmental power.Source: https://artreview.com/november-2013-opinion-mike-watson-on-power-and-disobedience/

The Disobedience Archive

(fragments)

by Martina Angelotti

The year 1968 was marked by division and a collective, political, and existential explosion. In Italy, it was the prelude to the clashes at FIAT Mirafiori and the major strikes that quickly led to the Hot Autumn. The poet, novelist, and artist Nanni Balestrini produced numerous works about this difficult period in Italian history, transforming the linguistic space into a public space for political reflection belonging to the community. It is not surprising, then, that the Castello di Rivoli in Turin was the first Italian venue chosen for Disobedience Archive (The Republic), an exhibition curated by Marco Scotini, nor that a collage by Balestrini opens (or closes, depending on the direction of the route) the section of ephemera that contextualizes the exhibition in a parliamentary antechamber composed of documents, publications, objects, and works. What Parliament? The one designed by artist and architect Céline Condorelli as an exhibition device for visitors to engage with and explore the filmic legacy collected by Disobedience over the course of its extensive trajectory, initiated about a decade ago.

The Parliament is arranged in a fragmented circle divided into four semicircular sections. Unlike a real parliament, these are physically separated by the museum walls into four interconnected but independent rooms. This is not an institutional structure designed to ensure debate and dialectic between an elected majority and its opposition—which defines the very essence of parliamentarism. Rather, it is an attempt to bring the voice of dissent and social reconfiguration to a non-representational republican charter.

It is a contingent archive expressed in the “here and now” of the exhibition. That the event takes place in Turin—or more broadly, in Italy—is not coincidental, especially when one considers the national political situation, where the Chamber of Montecitorio has repeatedly subjected democracy to extreme tensions due to an already endemic conflict between politics and the judiciary, as well as among multiple state institutions. It is not about thinking separately of Art (with a capital A) and Politics (with a capital P), but about recovering a natural blending capable of building a “grammar”—to borrow from Foucault—that includes both major and minor languages, yet equally recognizable.

If aesthetics consist in granting visibility to what previously had none, it is difficult not to see this Disobedience Archive experiment as an aesthetic act in itself. It not only centers reflection on the language of activist cinema but also turns the practice of disobedience into one of the Fine Arts, as Marcelo Expósito—an artist-activist present in the archive since its beginnings—proposed.

Each version of the exhibition changes form to embrace and promote the nomadic experience of an archive that becomes conscious, encourages the rewriting of movements, the sharing of self-empowerment practices, and the reconstruction of protest, thus developing a new aesthetic, didactic, and political choreography.

If activism and civic community confront us with a question—what do we do?—one possible answer is: disobey.Fuente: https://www.domusweb.it/en/art/2013/05/17/disobedience_archive.html