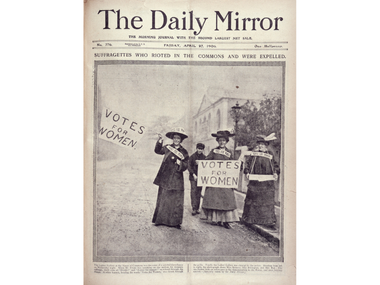

Newspaper article on suffragettes who protested in the House of Commons, in: The Daily Mirror, London, April 27, 1906 � The British Library Board

Newspaper article on suffragettes who protested in the House of Commons, in: The Daily Mirror, London, April 27, 1906 � The British Library Board

Reform and revolution (1900-1930)

Until the end of the 19th century, becoming a professional designer or enrolling in a university to study architecture was an option rarely accessible to/for? women. The few creative jobs considered appropriate, such as drawing teacher, required a certain social status. Even so, many women worked in design-related areas, often from their homes or in factories where authorship was rarely acknowledged.

From approximately/around? 1900 onwards, a series of changes in Europe and North America began to improve opportunities for women in the field of design. With the advance of industrialization, design emerged as a profession with its own identity. The constant work of the women's movement paid off: the introduction of universal suffrage also meant the vote for women, and universities began to open their doors to them both men and women.

After the end of the First World War, a new way of thinking emerged throughout Europe, driven by avant-garde artists who renewed traditional visions. This movement motivated many women to join reform-oriented schools and communities, seeking new means of expression. However, the practice of design continued to be permeated by a strong bias that linked gender with specific skills and abilities.

Designing protest

Graphic design consolidated itself as a key tool in the construction of the suffragist movement, and its impact was evident in the proliferation of posters, flyers, and printed materials that took over public space.

British activists managed to articulate a clear and effective visual identity that amplified their political message. In 1908, the editor of the newspaper Votes for Women defined the color palette of the movement: white for purity, purple for dignity, and green for hope – colors that were used in flags and graphic materials. Furthermore, they chose to wear white dresses, which allowed women from different social classes to project a unified image. Both in daily life and in printed images, this palette guaranteed a visual impact in black and white graphic media, ensuring its dissemination.

In California, at that time, efforts to obtain the right to vote for women had failed, but when a new government took office in 1910, activists began to feel more hopeful. The designer Bertha Boyé (1883–1931) departed from a traditional image of women to disseminate the slogan of women's suffrage, claiming the right to vote and projecting confidence and optimism.

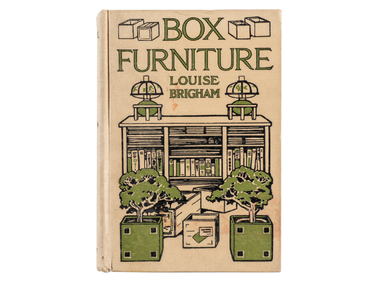

Louise Brigham, Box Furniture. How to Make a Hundred Useful Articles for the Home, 1919 Photo: Vitra Design Museum

Louise Brigham, Box Furniture. How to Make a Hundred Useful Articles for the Home, 1919 Photo: Vitra Design Museum

The social dimension of design

Although the term "social design" is relatively new, its principles and objectives have existed since the late 19th century, when committed individuals – mostly women – sought to improve the living conditions of the most disadvantaged sectors.

A clear example of this was the creation of Hull House in Chicago, a social center established in one of the city's most vulnerable areas. Conceived to support the growing immigrant population, the space offered classes in literature, art, and history, as well as craft workshops. The prominent group of volunteers came mostly from the upper class, serving as teachers and educators. The movement inspired Louise Brigham, a pioneer of DIY, who created guides for manufacturing accessible furniture without requiring advanced skills or special tools.

In the media

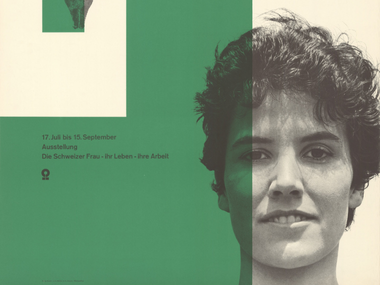

The Vienna World's Fair of 1873 was the first to dedicate a space to the life and works of women, marking a starting point for numerous "women's exhibitions" that would follow this event, such as De Vrouw (Woman), Salon des Arts Ménagers (Household Arts Salon), and the Swiss SAFFA (Swiss Exhibition of Women's Work).

The exhibitions tended to focus on sewing and other crafts that conformed to middle-class stereotypes of femininity, and presented professionals linked to family or social work. Magazines such as Die Welt der Frau (The World of Woman) and Gartenlaube (The Arbor) timidly began to address political issues raised by the women's movement, although they mostly dealt with childcare, housework, and fashion advice.

In 1912, the exhibition Die Frau in Haus und Beruf (Woman in the Home and Profession) was organized in Berlin, highlighting job opportunities. With the support of Fia Wille and Lilly Reich, the exhibition demonstrated the need for female income and hosted the Congress of German Women.

The campaigns of the feminist movement, initiated in the mid-19th century, led to greater awareness about the role of women in society.

Women at work

As industrialization accelerated in the mid-19th century, various movements emerged that criticized the mass production of low-quality objects and promoted the union between the arts and crafts to create beautiful and well-made products. New schools and workshops were founded that have become emblematic names, such as the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops), where women had the opportunity to study and work, and whose contribution is valued today.

Between 1898 and 1938, a notable group of women designers stood out for their work in the Hellerau workshops in Dresden, being recognized in the catalogs alongside the name of their designs – something innovative for the time, since it was then uncommon to publicly acknowledge women in the field of design. Prominent figures include Gertrud Kleinhempel and Else Wenz-Viëtor.

Emancipation and education

Few institutions have rivaled the reputation and prestige of the Bauhaus School. Founded in Weimar in 1919, the Bauhaus accepted women as students on equal footing with men, a stimulating idea in a context where most art schools excluded or discouraged their participation. However, many of the women who enrolled soon faced a disappointing reality: they were channeled into craft workshops traditionally considered feminine. In recent years, design historians have begun to recognize and study their contributions.

An interesting contrast is offered by the VkhUTEMAS art and design school, which operated in Moscow between 1920 and 1930: there, political conditions and institutional structure decisively influenced how possibilities, roles, and gender perceptions were conceived. Another universe still little explored by design history is that of the Loheland School, an artistic community also founded in 1919, which shared several principles with the Bauhaus. The fundamental difference was that Loheland did not admit men.

Alma Siedhoff-Buscher. Bauhaus Bauspiel, 1923 (2015) � Naef Spiele, Schweiz. Ph: Heiko Hillig

Alma Siedhoff-Buscher. Bauhaus Bauspiel, 1923 (2015) � Naef Spiele, Schweiz. Ph: Heiko Hillig

THE BAUHAUS: ALMA SIEDHOFF-BUSCHER AND MARIANNE BRANDT

Alma Siedhoff-Buscher (1899–1944) entered the Bauhaus in 1922. She began in the weaving workshop but managed to transfer to the wood carving workshop. At the great Bauhaus exhibition of 1923, she presented a children's room that attracted great attention, and from then on she decided to specialize in toys and children's furniture. Inspired by the Montessori method, Siedhoff-Buscher defined children's play as their "work" and designed robust and colorful toys to encourage their development.

Marianne Brandt (1893–1983) left her mark on the predominantly male world of the Bauhaus metal workshop. Her designs for metal utensils, decorative objects, and especially lamps, were produced in small series and are among the few objects that the Bauhaus successfully commercialized in collaboration with external manufacturers. In 1929, after her first major success—the Kandem lamp—the German company Ruppelwerk commissioned her to redesign its entire product line. Brandt was one of the first women to head the Bauhaus metal department.

VKhUTEMAS: ART AND SPORTS

The VKhUTEMAS art and design school in Moscow, founded in 1920, had an important parallel with the Bauhaus: both were born from the motivation to build a new society. In some of its courses, more than half of the graduates were women, and the senior faculty included several of them. Although the school administration did not segregate students, women were mainly concentrated in the faculties of sculpture, ceramics, and textiles, while there were fewer female graduates in painting, graphics, or architecture, and none in the wood and metal workshops. Sport was an integral part of school life, which was also reflected in the art and design works of the students. Varvara Stepanova, for example, designed unisex sportswear that guaranteed freedom of movement and featured bold constructivist prints and graphics.

Loheland photo workshop: Jump (Montage), c. 1930. Ph: Loheland-Archiv, K�nzell

Loheland photo workshop: Jump (Montage), c. 1930. Ph: Loheland-Archiv, K�nzell

LOHELAND SCHOOL OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION, AGRICULTURE, AND CRAFTS

The Loheland School in rural Hesse enabled women to qualify as gymnastics teachers, but its integrated curriculum also offered classes in dance, crafts, art, and economics. The progressive approach to education followed by its founders Louise Langgaard (1883–1974) and Hedwig von Rohden (1890–1987) embraced a new physical awareness and women’s emancipation. The school’s funding partly derived from the sale of products from its own pottery, weaving, and turning workshops, while dance performances in the big cities raised the school’s profile. The photography workshop headed by Valerie Witzlsperger also proved to be highly important to the school, since it documented its students’ expressionist dances, their community life, and their simple handcrafted products.

Pioneers of Modernism (1920-1950)

In Europe and North America – the Global North, as we call it today – the social upheavals of the early twentieth century had given women access to new education and career options in architecture and design.

While patriarchal patterns continued to lurk in the background, women designers began to make a name for themselves internationally and made their presence felt in existing, often male-dominated networks which they used to good advantage. They established their own studios and joined professional organisations and artist’s associations. Some collaborated closely with their partners, contributing to the joint works to a degree that research has only recently begun to appreciate fully. If they were frequently overshadowed by their partners, this was in line with social conventions that liked to see women as men’s helpmates, an image the media were all too willing to help foster.

A small number of women designers worked in complete independence. Others created signature works that came to stand for entire companies or became successful business leaders themselves, but they rarely sought the public limelight.

While most of the designers presented here have found a place in the history of design with exhibitions and catalogues to celebrate their works, design historians still have much to discover.

Poster for the Swiss Exhibition for Women's Work, SAFFA, Zurich, 1958. design by Nelly Rudin Plakatsammlung Schule f�r Gestaltung Basel, Copyright for Nelly Rudin: � VG Bild-Kunst

Poster for the Swiss Exhibition for Women's Work, SAFFA, Zurich, 1958. design by Nelly Rudin Plakatsammlung Schule f�r Gestaltung Basel, Copyright for Nelly Rudin: � VG Bild-Kunst

IN MOTION (1950–1990)

After World War II, design and architecture underwent an unprecedented period of dynamism in which the ideals of modernism were revived and reinterpreted. Technological progress fueled hopes for a new society where people would live in modern, light-filled buildings, with appliances that made everyday life easier and an abundance of consumer goods. It was a time of intense activity for designers. Many women managed to establish themselves in fields traditionally considered "male," such as architecture, furniture design, and academia, leaving a lasting mark on future generations.

However, in the West, female designers continued to face limitations imposed by traditional gender roles. Although production and consumption heavily relied on women, their role was largely confined to that of consumers, not producers or creators. Even so, many women succeeded in turning stereotypes to their advantage, capitalizing on their supposed domestic skills to build careers in design.

In socialist countries, by contrast, the situation was different: at least officially, women participated in the workforce on equal terms with men.

In the 1960s, demands for equal rights and opportunities intensified with the second wave of feminism, which challenged the conservative postwar mindset in the West. While there were few initiatives directly linking design with feminism, their impact was nonetheless significant.

GMs Damsels of Design, photographed c. 1955. From left: S. Vanderbilt, R. Glennie, M. Ford Pohlman, H. Earl, J. Linder, S. Logyear, P. Sauer. Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections

GMs Damsels of Design, photographed c. 1955. From left: S. Vanderbilt, R. Glennie, M. Ford Pohlman, H. Earl, J. Linder, S. Logyear, P. Sauer. Courtesy General Motors Design Archive & Special Collections

The woman's sphere

In the 1950s, the ideal of the housewife who stayed at home, cared for her family, and maintained cleanliness and order still prevailed in many Western countries. Some women designers managed to turn this stereotype into successful careers, and although the design canon largely ignored them, this was not only because their work was often perceived as having a distinctly “feminine” touch. The myth of the artist working and creating in total isolation is also deeply rooted in the field of design, yet women designers were often part of a larger team. And while Brownie Wise (1913–1992) may not have designed the iconic Tupperware containers, she did invent the innovative party plan system—home-based marketing through sales gatherings—for which the product became famous. The decoration Enid Seeney (1931–2011) created for the Homemaker dinnerware series, of which millions were sold in the 1950s, helped popularize the forms of postwar modernism. Until recently, these two designers were rarely mentioned.

Designing for life

The market for brightly colored printed textiles and wallpaper flourished with the postwar construction boom. More than in other areas of design, abstract and modern art became a major source of inspiration. In an effort to boost consumer demand, fairs such as the Werkbund association’s “Neues Wohnen” (New Living) exhibition in Cologne in 1949 or Britain Can Make It, held in London in 1946, helped bring modern design to the general public. Wallpaper patterns and upholstery fabrics were often created by women who had begun working with manufacturers after graduating from art school or studying textile design.

Teachers, university professors, academics

When evaluating the achievements of women designers, it is important to remember that many of them not only worked creatively but also played an active role in teaching. From around 1900, women were able to pursue disciplines traditionally deemed appropriate for them, such as drawing, embroidery, textile design, and ceramics. It is no surprise that the first Bauhaus workshop led by a woman—Gunta Stölzl—was the weaving workshop. Lucia DeRespinis, for her part, was one of the first women to earn a degree in industrial design from the Pratt Institute in New York. She graduated in 1952 and, years later, became one of the institution’s first female professors. Today, at the age of ninety-eight, she has devoted more than forty years to teaching. Many designers have left their mark on design history by passing on their knowledge and skills to new generations. Moreover, their teaching has helped consolidate lesser-recognized disciplines, such as textile and interior design, within the academic field.

Nanda Vigo. Light Tree (1984) and Cronotopo (1964), 1985. Ph: Gabriele Basilico, courtesy by Archivio Nanda Vigo, Milano

Nanda Vigo. Light Tree (1984) and Cronotopo (1964), 1985. Ph: Gabriele Basilico, courtesy by Archivio Nanda Vigo, Milano

A new generation

Although a growing number of institutes, universities, and art academies had opened their doors to women in the 1920s, it took many years before female graduates were no longer seen as daring exceptions. It was only after World War II that a new generation of highly qualified women emerged—women with excellent credentials and extensive professional networks. Like their male counterparts, they established studios and gained access to markets. In Italy, women designers often began their careers after graduating in architecture, while in the Nordic countries it was more common to train as a carpenter or cabinetmaker, or to study at a school of applied arts. Leading magazines such as Domus began to recognize the work of women designers, who also received awards and honors at international exhibitions.

Galina Balashova. Sketch of the Interior of the Orbital (Living). Compartment of the Soyuz Spacecraft. Variant 1, 1963. � The Museum of Cosmonautic, Moscow

Galina Balashova. Sketch of the Interior of the Orbital (Living). Compartment of the Soyuz Spacecraft. Variant 1, 1963. � The Museum of Cosmonautic, Moscow

Designing under socialism

In the European socialist bloc, women’s equality and independence were considered as important as collectivism. Many working women were responsible not only for their families and households but also for managing supplies amid ongoing shortages. Most women designers held degrees in engineering or design and went on to work for state-owned institutes or in so-called kombinats—large industrial conglomerates. In recent years, research has also begun to focus on the achievements of women designers from the socialist bloc.

Lina Bo Bardi. Stool for Centre SESC Pompeia, S�o Paulo, 1979/80. � Vitra Design Museum. Ph: Andreas S�tterlin, � VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

Lina Bo Bardi. Stool for Centre SESC Pompeia, S�o Paulo, 1979/80. � Vitra Design Museum. Ph: Andreas S�tterlin, � VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

Union

All design relies on close collaboration. A concept absorbs many ideas and passes through many hands before it is ready for production. A particularly interesting dynamic arises when two designers are partners both in business and in life. Today, in many parts of the world, their gender identity is largely irrelevant, and these couples can focus on working together as equals. But it took a long time for the role of women designers in the success of a firm to be acknowledged.

Patricia Urquiola. Shimmer, 2019 � Vitra Design Museum. Manufactured by Glas Italia. Donated by Glas Italia

Patricia Urquiola. Shimmer, 2019 � Vitra Design Museum. Manufactured by Glas Italia. Donated by Glas Italia

Faye Toogood. Roly Poly, 2018 � Vitra Design Museum. Fabricated by Driade

Faye Toogood. Roly Poly, 2018 � Vitra Design Museum. Fabricated by Driade

A broader view

1990 >> Today

Today, many women successfully run their own studios, working under their own names across diverse fields—from classic industrial design to social design that addresses humanitarian and community issues.

The binary view of gender—especially the one that links talent or creativity to sex—seems to belong to the past. Or does it? Since the turn of the millennium, a new wave of feminism has prompted ongoing reflection on the inequalities that still persist. There is no single feminism, but rather multiple currents that address a wide range of issues, from the gender pay gap to diversity.

Giving women a place in a male-dominated workforce and historiography is only part of the debate. It is also about questioning the dominant value systems at a deeper level. These concerns have now reached the field we are addressing today: has our perspective been too narrow? Too Eurocentric, too exclusive?

If we want our practice to have a positive impact on the future, we must critically examine both past and present in order to develop new models and methods. Conversations about feminism and design also offer ideas and inspiration for a new way of working—one that values cultural and ecological sensitivity, encourages interdisciplinarity, and is rooted in collaboration and experimentation. As we can see, many are already putting this approach into practice.

Julia Lohmann, In the Department of Seaweed Studio. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2013. Ph: Petr Krejci

Julia Lohmann, In the Department of Seaweed Studio. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2013. Ph: Petr Krejci

Design as research

Plywood, tubular steel, plastic, injection molding, 3D printing: the work of designers is closely tied to the ongoing pursuit of innovation, driving the development of new materials and manufacturing processes. Over time, design has become a key ally of industry—a relationship that, in recent decades, has increasingly come under scrutiny within the broader debates on sustainability.

In this context, women designers have played a fundamental role. They not only revisit the sources of raw materials but also rethink business models and production processes, advancing more responsible approaches. They recover traditional artisanal techniques, revive materials at risk of disappearing, and combine them with their own innovations to redefine the concept of innovation—prioritizing a conscious and sustainable use of resources beyond commercial interest.

Rethinking traditions

Design goes far beyond solving problems or specific tasks. Objects tell stories, place us within our culture, generate a sense of belonging, and reflect our customs and traditions. What does an object reveal about its origin or about the ideals of the society in which it was created? By questioning the formal and material conventions of everyday objects, contemporary women designers are paving the way toward a more diverse, inclusive, and open understanding of design—one that also embraces new perspectives beyond Western traditions. The objects created by Indian designer Gunjan Gupta, for instance, reference her country’s cultural history and rituals of movement, rest, and work. Meanwhile, the transdisciplinary studio BLESS designs everyday solutions that humorously challenge our expectations of everyday objects—and, in doing so, our own habits.

Interfaces

Design as a profession is becoming increasingly complex and multifaceted. It is less about the shape of objects and more about the integration of diverse fields of research to offer innovative—and at times provocative—responses to current and future challenges. Working in an interdisciplinary field demands a high level of specialized knowledge, but vision and teamwork are gaining ever more importance. These are precisely the qualities that characterize many women designers who, in recent years, have raised the bar of design methodology—for example, by harnessing solar energy or incorporating synthetic scent molecules. When design, the natural sciences, and information technologies converge, new products emerge that make our lives easier, help protect the environment, or invite critical reflection on new technologies.

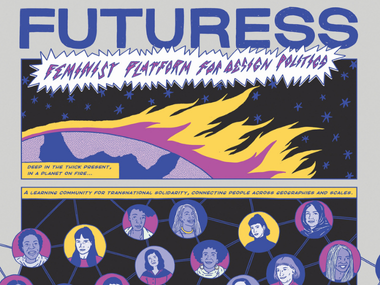

Illustration of the feminist Platform Futuress, 2021, � Maria Júlia Rêgo

Illustration of the feminist Platform Futuress, 2021, � Maria Júlia Rêgo

Here we are

With the arrival of the new millennium and the resurgence of feminism, design, too, has become the subject of new research and critical debates. A feminist perspective on design history has not only exposed the predominance of male figures, but also revealed that both the designs and texts forming the global design canon largely come from a small number of authors from Western cultures. The initiatives presented here reflect ongoing efforts to counter these inequalities. A new generation of designers is working to bring visibility to the legacy of their predecessors, while major educational institutions are beginning to engage in debates on gender and marginalization. At the same time, feminist actors are challenging academic elites and building more democratic training networks. The need to construct new narratives—with a language to match—has also become a central concern within design.

Argentine Designers: a chronology of a vocation

by Silvia Fernández

1930: The First Decades of the 20th Century in Argentina

In the early decades of the 20th century, Argentina experienced a major demographic phenomenon. In just twenty years, the idea of a homogeneous society was dismantled, giving way to a more visibly "mixed society." Female subjugation under the patriarchal order—stereotyped by devotion to home and domestic responsibilities—brought into question the exclusionary model and raised debates on women’s right to vote, the legalization of divorce, civil rights, access to university education, and gender equality.

1931: Actors and Media Shaping the Intellectual Field

Actors and media made up the intellectual field where emerging forms of modernity interacted. The magazine Sur (1931), directed by Victoria Ocampo, became a reference for the arts, literature, and culture, circulating avant-garde ideas in balance with classical ones. Ocampo also designed the magazine’s cover.

1935: The Arrival of Horacio Coppola and Grete Stern

In 1935, photographers Horacio Coppola and Grete Stern settled in Buenos Aires, becoming key figures in bringing Bauhaus aesthetics and theory to the city. In addition to her photography, Stern created innovative design pieces, including the magazine Idilio for Editorial Abril, among other publications. She also worked on graphic design for catalogues and advertisements.

1940–1950: Women’s Political Rights and the Modernization of Design

Distributive policies, women’s suffrage, and political rights during Juan Perón’s administration—especially the female vote, advocated and secured by Eva Perón—were essential for women’s access to public and political life. Between 1947 and 1955, state visual communication coexisted with autonomous visual environments.

Modernization took root in the 1950s, as a new generation of architects, painters, and designers deepened the modernist utopia, often incorporating regional elements. Notable figures include Celina Arauz de Pirovano, Lidy Prati, Colette Boccara, and Lala Méndez Mosquera. Modernity coexisted with local, traditional, and folkloric forms of representation, as seen in the designs of Aurora de Pietro de Torras.

1955–1972: Lidy Prati and Editorial Design

Between 1955 and 1972, Lidy Prati worked on editorial design projects such as Mundo Argentino, Artinf, and Lyra, and collaborated with architect Amancio Williams. In 1972, she created the graphic design for Argentina’s participation in the Venice Biennale.

The 1960s: Modernity and Women’s Participation

In the 1960s, the concept of modernity aligned with the industrial development program of Arturo Frondizi’s government, marking a turning point for design and urban culture in Argentina. Women began to take an active role in Buenos Aires’ professional and cultural life. With increased individual freedom, more rights, greater economic independence, and rising gender awareness, many designers worked in studios alongside their husbands or partners. Among them were Colette Boccara–César Janello, María Luisa–Julio Colmenero, Lala–Carlos Méndez Mosquera, and Eduardo Joselevich.

1958–1963: The Beginning of Design Programs and Institutions

Starting in the late 1950s, the first two design degree programs were established at the National University of Cuyo (1958) and the University of La Plata (1963). During the 1970s, enrollment grew significantly, with high female participation. Additionally, the Instituto Di Tella, founded in 1958, became a hub of innovation and openness in Argentine design, especially between 1965 and 1970.

CIDI (1962–1988): Argentine Design and the Crisis of Female Participation

CIDI (1962–1988) was a landmark institution for Argentine design, linked to industrial development in the 1960s. However, the androcentric belief that fields like architecture and design were gender-neutral has been disproven by recent studies showing a significant gender gap in government roles, juries, and awards.

1970–1976: The Coup and the Design Crisis

Between 1970 and 1973, Argentina experienced a climate of confrontation and unrest, culminating in Perón’s return to power in 1973 and the military coup of 1976. During the dictatorship, the ruling junta dismissed technological development, leading to a decline in the design profession. Institutions and agencies went into crisis, prompting many professionals to emigrate. Nonetheless, leftist movements produced clandestine graphic work focused on editing and distributing magazines.

1983–1990: Democratic Recovery and the Rise of Graphic Design

With the 1983 presidential election and return to democracy, women in design gained new freedoms to actively shape cultural life. This democratic recovery opened doors to greater female participation. In this context, designers like Tite Barbuzza and Ángela Vassallo rose to prominence. In 1994, Vassallo founded one of the largest design studios in Buenos Aires.

1990: Economic Crisis and Industrial Design

In the early 1990s, amid economic crisis and privatization under Carlos Menem’s government, design began to take on major projects in areas like institutional identity and industrial design. Zalma Jalluf, through Fontana Diseño, led the development of large-scale corporate visual programs.

In opposition to this market-driven design approach, and within the framework of graphic activism, Anabella Salem and Gabriel Mateu founded El Fantasma de Heredia in 1993 — a graphic design studio focused on social and cultural issues. In 1988, the University of Buenos Aires created the Apparel and Textile Design program, paving the way for designers like Vicky Otero and Jessica Trosman.

2000–2020: Feminist Activism and Technological Advances

In 2000, the World March of Women took place in fifty countries, including Argentina, as a reaction against capitalism and patriarchy. In 2010, the “green tide” emerged as a social movement in favor of legal abortion, culminating in the 2020 approval of the Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy Act. This period also saw major technological advances, including digital technology, artificial intelligence, and the expansion of women’s rights.

Design and Feminism in the 21st Century

Over the first two decades of the 21st century, feminism gained strength, leading to increased female participation in design. In Argentina, collectives such as Mujeres que no fueron tapa (2015), Cooperativa de Diseño (2011), Hay Futura (2019), and Colectivo de diseño – Bariloche (2015), among others, challenge patriarchal structures within the design field.

Architect Diana Cabeza also stood out. Her emblematic works—such as the Topographic Bench and her role in the Buenos Aires Metrobús project—reflected her deep sensitivity to public space and social integration.

Interview with Adriana Rosenberg

This interview was conducted by the Press Department of Fundación Proa.

Proa reopens its renovated galleries with an exceptional exhibition on the history of design by women. What makes this exhibition particularly relevant, especially in comparison to previous design-focused shows presented by Proa?

I believe this exhibition brings together two important aspects. On the one hand, it recovers the history of women in design—a history that had not been widely researched and is only now beginning to gain relevance. On the other, it shows how, since the early 20th century, women began studying and entering the field, eventually becoming highly influential today. What’s extraordinary, in my view, is the opportunity to appreciate the connection between the history of design and art, and the evolution of the 20th century through objects that represent the groundbreaking work of many women.

The exhibition spans 120 years of this discipline. What are some of the key milestones in that evolution reflected in the pieces on display?

The exhibition begins with the early struggles of women to find their place. What’s interesting is that this historical journey reveals the development of new technologies within various social and political contexts of the last century—and also today—showing how things evolved as women joined the workforce and new materials like plastic emerged. In other words, it highlights how the world changed in parallel with women gaining independence. From living anonymous lives doing needlework or studying at art schools, engaging in craft-based work, to now becoming competitive professionals on equal footing with men.

Looking at the works on display, can we identify a specifically European conception in the way design addresses everyday needs?

Although there are many American designers featured, the exhibition is predominantly focused on European figures. That framing is evident—it could be said that the rest of the world is missing—but it’s true that these designs once dominated the global scene. Nearly all the furniture exhibited made its way to Argentina, largely thanks to the concept of mass design—a movement that transcended borders by democratizing access to pieces conceived as unique.

Do you believe there are recurring traits in the work of women designers across different times and contexts?

It’s difficult to pinpoint distinctly “feminine” or “masculine” features in design. Most of the pieces were conceived with sensitivity to meet a particular demand. This suggests that creativity in design isn’t bound to gender, since it responds to functional, aesthetic, and contextual needs rather than the identity of the creator. That said, certain trends or approaches can be observed in specific times and places, shaped by cultural, social, and educational influences. These may be reflected in choices of material, typology, or concept—but not as exclusively gendered characteristics. Rather, they form part of a creative ecosystem in constant transformation.

This isn’t the first time Proa has presented a design exhibition.

Over the years, we’ve organized several exhibitions related to design—for instance, New German Design in 2000, which focused on recycling, sustainability, and the social impact of design, showing how these concerns have long influenced the profession. Later, Design in Action in 2019 featured a group of young Argentine designers addressing issues in architecture, ceramics, and fashion. This current exhibition allows us to revisit the role of design throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, highlighting its enduring ability to offer innovative responses.

Fundación Proa has often paired international exhibitions with local content. What was the selection criteria for the Argentine pieces accompanying the Vitra Design Museum exhibition?

The Argentine section is organized in parallel with the curatorial structure of the thematic clusters presented by Vitra. We included a video that introduces the audience to Argentina’s early 20th-century social and political context—highlighting women’s suffrage, labor in factories, and artisanal work. Then, from the 1950s onward, when authorial design emerges in Argentina, we dedicated two significant sections—one focused on mid-century work and the other on contemporary contributions. Together, they present a selection of emblematic national pieces in dialogue with Vitra’s collection, enriching key aspects of this historical review.

What design features are highlighted by this selection, and what connections can be drawn with the designers represented in the international exhibition?

Adding an Argentine chapter to the Vitra Design Museum exhibition creates a bridge between two ways of understanding design: the European model, known for industrial precision, formal rationality, and a focus on efficiency, and the Latin American model, defined by experimentation with local materials, adaptability to shifting economic realities, and a strong artisanal component. While European design has been historically tied to mass production and schools like the Bauhaus, here—though in dialogue with avant-garde movements—design often emerges from the need to solve problems creatively with limited resources. This collaboration with Vitra not only allows local audiences to access original iconic pieces and innovative curatorial perspectives, but also fosters a conversation between materialities, functionalities, and modes of making.

LISTADO DE OBRAS COMPLETO

LISTADO DE OBRAS COMPLETO