Presentatiton

The Exhibition

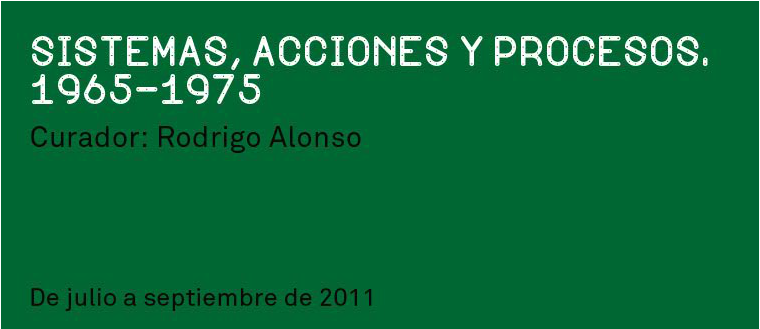

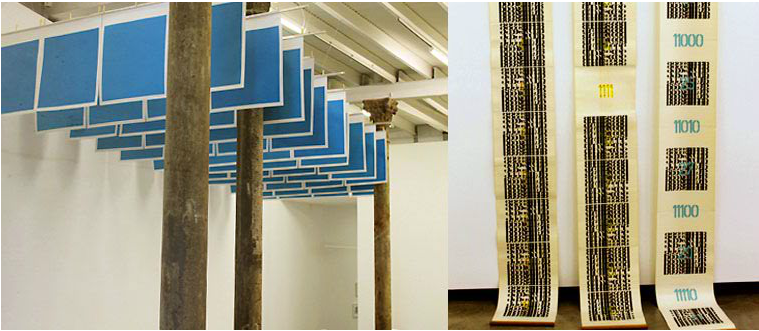

Oppose the system. Expand artistic languages. Investigate the world. Starting on Saturday, July 23, Fundación Proa, with the support of Tenaris/Organización Techint, is presenting Systems, Actions and Processes. 1965–1975, an international exhibition curated by Rodrigo Alonso.

The exhibition consists of over one hundred drawings, paintings, sculptures, photographs, videos and registers of performances and art actions from a crucial historical period, the 1960s and 70s. Creative explosion, political intensity and the redefinition of the role of art in society over the course of ten decisive years.

A breadth of aesthetic currents –conceptual art, minimalism, arte povera, performance art, process-based creation– in a show that, according to its curator, “draws attention to a moment when aesthetic categories proved incapable of categorizing the breadth and range of artistic production.”

With major works by Dan Graham, Carl Andre, Mel Bochner, Joseph Beuys, On Kawara, John Baldessari, Horacio Zabala, Víctor Grippo, Alberto Greco, Luis Benedit, Cildo Meireles, Juan Carlos Romero, Edgardo Vigo, Jaime Davidovich, Guillermo Deisler, Bruce Nauman, Alfredo Portillos, Claudio Perna, Graciela Carnevale, Antoni Muntadas, David Lamelas, Leandro Katz, Nicolás García Uriburu, Marta Minujín, Roberto Jacoby, Margarita Paksa, Raúl Escari and others, Systems, Actions and Processes. 1965-1975 provides an exhaustive overview of a critical moment in 20th-century art.

The body. The emergence and spread of technology. The centrality of politics. Urban explosion and nature as possibility. These are the themes that run through this exhibition’s four galleries.

In 2010, Rodrigo Alonso examined the internationalization of Argentine artists in an exhibition, held at Proa, entitled Magnet: New York. Systems, Actions and Processes. 1965-1975 evidences a decisive later moment when those Argentine artists were compared to and operated alongside major artists on the international scene.

The exhibition is accompanied by the publication of a major catalogue with seminal texts by Lucy Lippard, John Chandler, Lawrence Alloway, Cristina Freire, Mel Bochner, Hélio Oiticica, Oscar Masotta, Ana Longoni and others, which serve to broaden the curatorial reading.

On Saturdays, the Artists + Critics program, which consists of guided tours of the exhibition with specialists, allows other essential voices – those of direct participants in those years and its movements, as well as of curators and researchers– to participate.

In the framework of the exhibition, the Systems, Actions and Processes. 1965-1975 International Colloquium provides a close examination of the artistic problematic addressed by the exhibition. Thanks to the visit of philosopher Hervé Fischer and theorist Alexander Alberros, as well as the participation of Ana Longoni, Rodrigo Alonso, Cristina Freire and Fernando Davis, this colloquium is a platform from which to reactivate the most relevant questions concerning conceptual art and its varied extensions.

The works in Systems, Actions and Processes. 1965-1975, which are from the Júmex Collection (Mexico), the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (MACBA, Barcelona) and private collections, open another chapter in the revision of 20th-century art, which is one of the founding aims of Proa, possible thanks to Tenaris – Organización Techint’s commitment to support and experimentation.

“Systems, Actions and Processes. 1965-1975” by Rodrigo Alonso

Fragment of the curatorial text published in the catalogue Systems, Actions and Processes. 1965-1975:

History has come to see the 1960s as one of the most intense, controversial and creative decades of the 20th century. All spheres of thought, society and culture underwent crisis and innovation, questioning and rupture. By means of a sort of feedback process, different realms of human activity came to interact and intersect. Thus, a revolution in Cuba or a war of liberation in Algeria was capable of altering philosophical reflection, while a rock concert became a powerful political protest.

Revitalized Marxist theories gave rise to a vision of mercantile capitalism, the remains of colonialism, and political and cultural imperialism as models of a repressive and coercive system that tended to abolish social potentials which, in its view, had to be combated and eradicated. The “struggle against the system” became an imperative for a youth determined to change the world in defense of community ideals and individual liberties. Where there was no struggle, there was, generally speaking, resistance. In any case, throughout the 1960s there was a growing sense of discomfort with regimes that sought to reconstitute social life according to the demands of industrial production, the free market and powers at an ever greater remove from the persons that they supposedly represented.

Marx’s examination of social structures in his political theory resonated and was extended in structuralism, whose various strains affected all realms of thought. Human environments came to be understood as systems of relations based on more or less rigid orders that determine even the details of their functioning. In the field of linguistics, interest no longer focused on the content of a proposition but rather on the way that it builds meaning by complying with certain rules of formation. Jacques Lacan argued that the unconscious is structured like a language, while Claude Lévi-Strauss analyzed non-Western societies on the basis of the distribution of the kinship connecting its members. The study of prisons, insane asylums and medical procedures led Michel Foucault to formulate a social theory based on a complex system of power relations. Structures that seemed to govern everything became the object of rigorous analysis. These structures were the basis for a new understanding of reality that was no longer satisfied to limit itself to manifest information or the observation of facts and phenomenon; instead, there was an attempt to ferret out the deeply rooted mechanisms that govern the human universe beyond the readily evident.

All of this affected the sphere of art, albeit in very different ways. On the one hand, a renewed interest in analysis of the sort that characterized the early 20th century avant-garde –although without that earlier avant-garde’s aspirations to universal validity– led artists to interrogate the mechanisms of discourse and the meaning of their practice. This veer towards intellectual and methodic investigation was also a reaction against the over-valorization of gesture and subjectivity that characterized Abstract Expression. Another group of artists, one increasingly concerned with the political scene of the time, took an interest in systems, relations and processes as means to interrogate the social world. Out of an eagerness to take a stance “against the system,” some artists opted for non-systemic and supposedly freer creation, eschewing any model or categorization.

(...)

Systems, actions and processes at the dawn of conceptualism

According to art history, the period between 1965 and 1975 witnessed the beginning of conceptualism and its formation as an aesthetic category. Nonetheless, due to the multiplicity and breadth of production from those years, it is not hard to grasp that conceptualism was only one component of a cartography much more complex than the one that has been passed on to us in later genealogies.

One of the most glaring absences in these narratives is the notion of connection. Not only the connection born of the temporal coincidence of minimalism, kinetic art, conceptualism, the anti-form movement, Pop Art, eccentric abstraction and arte povera, but most importantly the connections established by the main players in these varied movements when they formulated their ideas and practices. Thus, just as Germano Celant made implicit reference to minimalism when he spoke of an industrial and “rich” art as opposed to the povera aesthetic, conceptual artists made frequent reference to their minimalist peers and even to painters like Ad Reinhardt. Indeed, one of Joseph Kosuth’s most incisive observations of conceptualism was born of a reflection on a piece by Donald Judd:

“One could say that if one of Judd’s box forms was seen filled with debris, seen placed in an industrial setting, or even merely seen sitting on a street corner, it would not be identified with art. It follows then that understanding and consideration of it as an artwork is necessary a priori to viewing it in order to 'see´ it as a work of art. Advance information about the concept of art and about an artist's concepts is necessary to the appreciation and understanding of contemporary art.”

Curator

Rodrigo Alonso

Research assistant

Jimena Ferreiro Pella

Coordination - Production

Maia Persico

Expository and Graphic Design

Fundación PROA

Conservation

Teresa Gowland

Montage

Soledad Oliva

Pablo Zaefferer

Education

Paulina Guarnieri

Rosario García Martínez

Collections

Mel Bochner, New York

Graciela Carnevale, Rosario

Centro de Arte Experimental Vigo, La Plata

Colecciones privadas, Buenos Aires

Colección Franklin Espath Pedroso, Rio de Janeiro

Daros Latinamerica AG, Zurich

Jaime Davidovich, New York

Mirtha Dermisache, Buenos Aires

Agnes Denes, New York

Document-Art, Buenos Aires

Electronic Arts Intermix, New York

Fundación Nicolás García Uriburu, Buenos Aires

Galería del Infinito, Buenos Aires

Henrique Faria Fine Art, New York

Leslie Tonkonow Artwork + Projects, New York

Nara Roesler, Sao Paulo

Carlos Ginzburg, Rueil-Malmaison

Roberto Jacoby, Buenos Aires

Juan Downey Foundation, NewYork

La Colección Jumex, Mexico

David Lamelas, Buenos Aires

Leopoldo Maler, La Romana

Marta Minujín, Buenos Aires

Antoni Muntadas, Barcelona

Museu d’ Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA)

Margarita Paksa, Buenos Aires

Alfredo Portillos, Buenos Aires

Juan Carlos Romero, Buenos Aires

University of Iowa, Iowa

Horacio Zabala, Buenos Aires

With the support of